Legal eagles have come out in support of the Harun R. Khan committee’s decision to recommend the removal of the “opaque structure” clause in the regulations governing foreign portfolio investors (FPIs).

They have also challenged the popular notion that the change amounted to a dilution of disclosure standards for FPIs — a view that gained currency after the Supreme Court-appointed panel came out with a report that appeared to support that view.

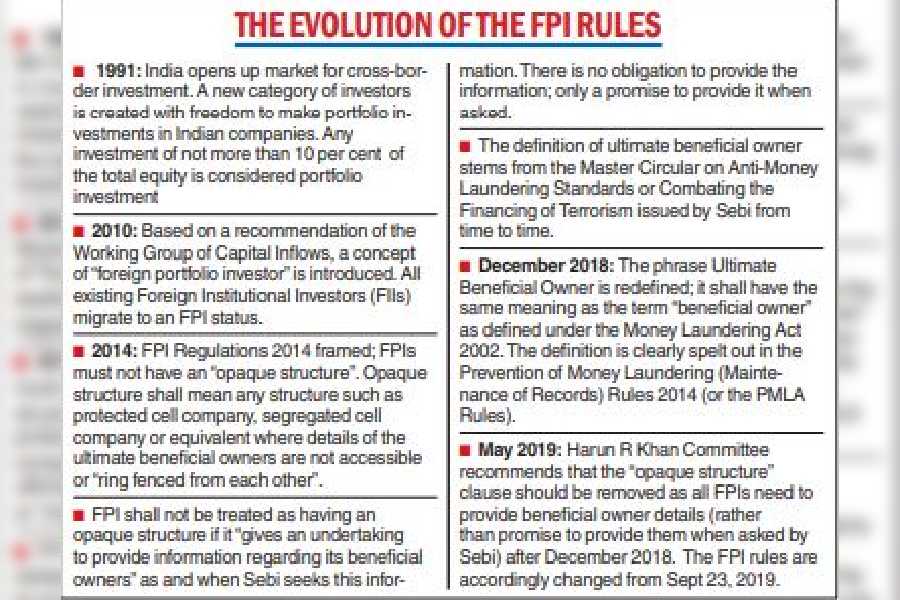

The decision to scrap the “opaque structure” clause turned controversial recently when the six-member Supreme Court-appointed panel of experts headed by former apex court judge Abhay Sapre said it was unable to conclude that there was a “regulatory failure” on the part of market regulator Sebi, which was investigating accusations against the Adani group for violating rules that require every privately-owned listed company to maintain a minimum public float of 25 per cent at all times.

The group has also been accused of failing to disclose all of its related party transactions and manipulating its stock prices.

The enquiry into the antecedents of the money through the FPIs linked to the Adani group “hit a wall” — the evocative expression that the Supreme Court-appointed committee of experts used in its report — because a chicken-and-egg situation had arisen after the FPI regulations were diluted in 2019 by tossing out the “opaque structure” clause.

However, Siddharth Shah, a partner with Khaitan and Co, reckons that there was no dilution in disclosure standard in 2019.

“Somehow, there is a notion that the earlier FII regime required identification of every underlying investor/shareholder. There has never been such requirement laid down for custodians/DDPs,” says Shah, who is a senior corporate and fund lawyer. DDP stands for designated depositary participant.

Market participants suggested the crackdown on the “opaque company structure” in the FPI Regulations of 2014 was the direct fallout of the Ketan Parekh scam when unscrupulous investors resorted to all kinds of artifices to evade regulatory scrutiny.

Back in 2014, Sebi felt that these foreign investors were using two main artifices — setting up protected cell companies or using a segregated cell company structure – to route money into India.

As a result, the regulator was unable to “identify who were really behind those structures” and it, therefore, decided to slap a ban on these structures in the first set of regulations that it framed for FPIs.

But as the regulatory and legislative landscape started to change around the world — with the introduction of Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and refined global reporting standards — the committee headed by Harun Khan, former RBI deputy-governor, rightfully believed in 2019 that the time had come to remove the curbs on opaque structures, say legal experts.

Moreover, these entities were ring-fenced — not against disclosures but against liabilities arising from sourcing investments or from the point of view of ensuring cost efficiencies.

Watch on definitions

The focus now is on the concept of ultimate beneficial ownership and there is no compelling reason today to persist with the restrictions or use the term opaque structures. Therefore, in that sense, there hasn’t been a dilution of standards.

“The current structures used by FPIs need not be opaque simply based on the structure. For example, merely a structure that allows for ringfencing or segregation of liabilities among different funds or investors — should not be considered opaque so long as there is a transparency of the UBO for each class/entity,” said Shah who is based out of Mumbai.

Even though the FPI regulations 2014 used the phrase “ultimate beneficial owner”, it did not actually define the term. Instead, it said the definition of the term “shall be as provided under the Master Circular on Anti-Money Laundering Standards or Combating the Financing of Terrorism, issued by the Board from time to time”.

From December 2018, Sebi said the definition of the “ultimate beneficial owner” would be derived from Rule 9 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA). If this stipulation was breached, the FPI would lose its licence.

The PMLA rule laid down different criteria to identify the beneficial owner:

■ If the client was a company, the beneficial owner was the natural person who, acting alone or through one or more juridical persons, had a controlling ownership interest which was described as “an ownership or an entitlement to more than 25 per cent of shares or capital or profits of the company”.

■ In the case of a partnership firm, the beneficial owner was the natural person entitled to more than 15 per cent of capital or profits.

■ In an unincorporated association or body of individuals, the beneficial owner would be natural person or persons entitled to more than 15 per cent of the property or capital or profits.

■ Where no natural person was identified, the beneficial owner would be the relevant natural person who held the position of senior managing official.

■ Where the FPI’s client was a trust, the beneficial owner would be identified as the author of the trust, the trustee, the beneficiaries with 15 per cent or more interest in the trust or any other person exercising ultimate effective control.

Under the FPI Regulations 2014, the responsibility of ensuring that the FPI did not have an “opaque structure” lay with the depositary participant with which the FPI was registered. The Khan committee had felt that the test to determine the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) needed to be harmonized.

It recommended that the “opaque structure” clause should be scrapped and Sebi accepted this recommendation from August 21, 2019.

Lawyers conversant with FPIs claim that nowhere in the world does any regulator insist that the last natural person in the line must be identified as the beneficial owner. “If that were to happen, the cost of doing business would become prohibitive.”

“The KYC obligations and thresholds for beneficial owner identification were never clearly spelt out, which led to confusion amongst custodians/DDPs who applied different thresholds on the FPI applicants. Hence, aspart of the rationalisation of the FPI regime, it was rightly felt that it would be important to provide clarity and certainty on the thresholds for identification of BO and hence had proposed aligning the same to the threshold identified under PMLA. That is fairly logical and also the right approach,” says Shah.