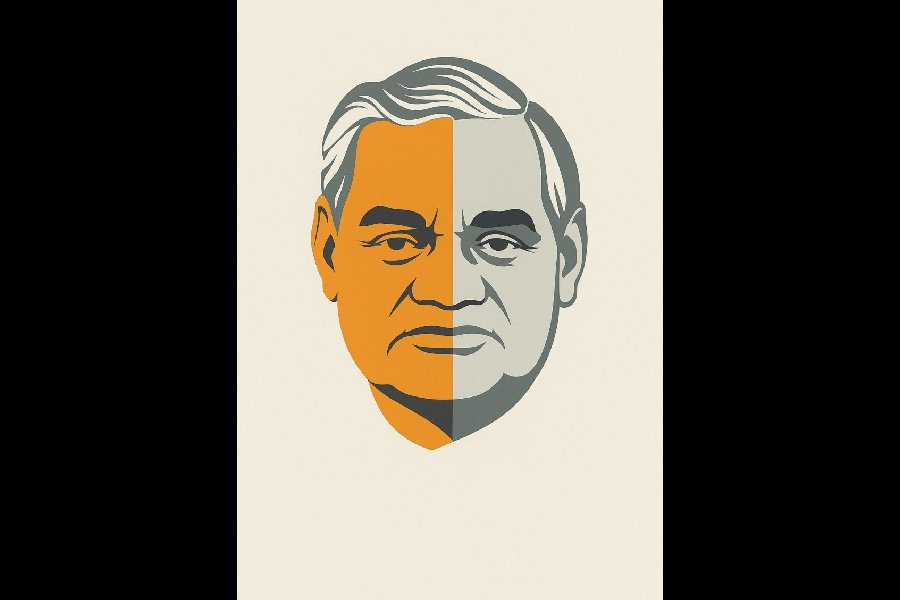

Book: BELIEVER’S DILEMMA:VAJPAYEE AND THE HINDU RIGHT’S PATH TO POWER, 1977-2018

Author: Abhishek Choudhary

Published by: Picador

Price: Rs 999

To read history is to read the present.

There’s a seductive comfort in believing that extremism arrives suddenly, that democracies collapse overnight. But the accidents of history weren’t random events but dominoes in a sequence that led inevitably to where we stand today. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, often remembered as the ‘right man in the wrong party’, was perhaps the right man for the Bharatiya Janata Party’s long game. Today’s BJP was incubated in the contradictions of Vajpayee’s era. Therefore, understanding Narendra Modi requires an understanding of Vajpayee.

In Believer’s Dilemma, Abhishek Choudhary, through the chronicling of Vajpayee’s political journey, interrogates the very nature of democratic mutation in postcolonial India. Starting with the chaotic, post-Emergency Janata experiment, a coalition that collapsed as inevitably as it had formed, he charts how failure became fertile ground for the Hindu Right’s patient cultivation of power. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which had once been relegated to the margins for “its paramilitary drills, its hatred of Muslims, its involvement in Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination”, gradually rewrote its story from a militant organisation to a cultural movement to a political kingmaker.

A common recurrence within these pages is how democratic institutions can become vehicles for their own subversion. Take Indira Gandhi’s once-hostile relationship with the sangh parivar: her post-Emergency weakness compounded by personal grief over Sanjay Gandhi’s death, which led her to turn a blind eye to the growing influence of the sangh parivar. Or consider her government’s insertion of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale to capture the Akali Dal’s voter base in Punjab, a tactical move that would spectacularly backfire, leading to years of militancy, insurgency, and ultimately Indira’s own assassination. It’s a self-repeating pattern: short-term political gains creating long-term institutional damage.

The BJP’s trajectory follows this same logic. Its brutal thrashing in the 1984 Lok Sabha elections, combined with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s wildly successful Ekatmata Yatra, taught it what the RSS had been preaching for years: Vajpayee’s moderation was unnecessary, political suicide even; mobilisation around Hindu identity was electoral gold.

The sequence of events inadvertently demonstrates the RSS’s superior understanding of the fundamentals of the Indian political reality. While secular governments hence operated on the naive assumption that pluralistic values could be imposed from above, the Hindu Right understood that sustainable politics required meeting existing demand. The success of organisations like the Arya Samaj and the pre-independence RSS had always signalled this demand. The BJP’s eventual dominance was the inevitable result of finally giving customers what they wanted after decades of being told what they should want.

Taking inspiration from Balasaheb Thackeray’s sectarian turn in Maharashtra, which had transformed the Shiv Sena from a linguistic movement into a majoritarian juggernaut, the BJP realised that the Ram mandir could serve as its own mobilising mythology. What had worked for Thackeray in one state could work for the party nationally. And work it did.

Vajpayee’s subsequent embrace of the Ram mandir movement, thus, was an institutional adaptation to democratic realities: “reporters who had covered his rallies at the same venue were ‘stunned’ by the new tone of the right wing’s most measured voice.” This raises uncomfortable questions about the nature of Vajpayee’s celebrated ‘moderation’. Was it principle or performance? Choudhary’s evidence suggests largely the latter. He “chose to mishear what other speakers on the stage and the crowd below were chanting (...) one part of the crowd below him chanted, ‘Kill all the Muslims now!’ When this was pointed out later, Vajpayee’s response was shock followed by convenient denial: ‘Oh no, they couldn’t have done that. No, I don’t think that was so.’”

Choudhary’s journalistic background serves him well in composing a political biography that reads like a thriller. “Driving along a dusty road in the scorching June heat, Vajpayee stopped near a roadside well to drink water from the bucket of a farm labourer. He asked the man which party he would vote for. ‘Janata,’ came the reply. Why? ‘If we have given kurta should we not give dhoti along with it?’” With an ear for

dialogue and an eye for the

revealing gesture, his writing reflects the interweaving

of the personal and the political.

In documenting Vajpayee’s journey, Choudhary inadvertently writes the story of how moderates become midwives to extremism. The India that emerges from Vajpayee’s era spawned the India we live in now.

And so it is, that to read history is to read the present.