Book: The Other Mohan in Britain's Indian Ocean Empire

Author: Amrita Shah

Published by: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs. 699

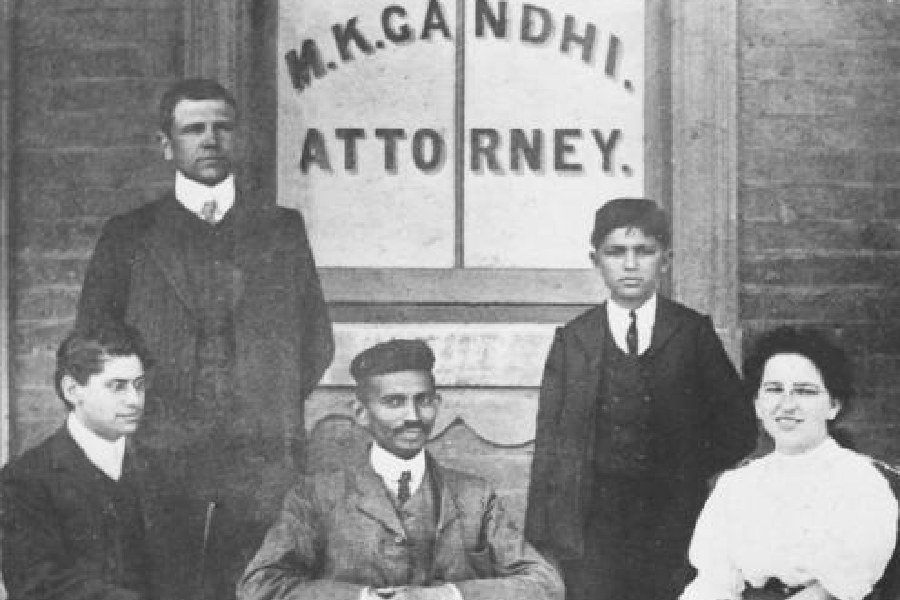

Amrita Shah’s book defies any form of critical segregation even though it promises to be “part travelogue, part memoir” and “part family history”. As Shah confides in the Prelude, her great-grandfather, Mohanlal Parmanandas Killavala, triggered her commitment to undertake the research for the book, especially when she learnt of his active participation in the 1908 protest campaign led by Mahatma Gandhi in Transvaal. The biggest — self-inflicted — challenge of Shah’s book perhaps lies in sustaining her titular promise of comparing the two ‘Mohans’, as is delineated in the introductory note: “Perhaps it was the infectiousness of this playful spirit that led me to consider the coincidence of two Mohans in the same space and at the same time as a narrative device.”

Shah’s unenviable exercise leads her to undertake an assiduous reconstruction of the life story of the protagonist. Although originally hailing from Surat, Mohanlal was born into a vania family that had later moved to Bombay. As a young man, driven both by the travel bug and the lure of a better career, Mohanlal initially set out for Mauritius, getting married to Foolkore (a Creole girl in all probability) in due course of time. Subsequently, the couple sailed to Durban in Natal. Following his arrival at Durban, Mohanlal eked out his existence as a clerk-cum-accountant in various solicitors’ firms, most notably with Archibald Findlay’s on the West Street.

Shah’s indefatigable efforts to reconstruct Mohanlal’s stay in South Africa are based on multiple anecdotes, some which make for interesting reading. One of them pertains to Mohanlal’s application for permission to keep a sporting rifle which was ultimately rejected, as testified by his correspondence with the Undersecretary for Native Affairs. Speculating on the reasons behind Mohanlal’s keenness to procure a sporting rifle, Shah links it to his probable intention to join some of the sports clubs run by educated Indians. While focusing on Mohanlal’s struggle, Shah manages to adroitly explore the plight of Indians living in South Africa: racial discrimination, disproportionate taxation, and the humiliating fingerprint registration, to mention a few of the challenges.

The seventh part of the book, titled “Satyagraha”, tries to explore Mahatma Gandhi’s passive resistance at Transvaal in detail while simultaneously indicating the ancillary presence of Mohanlal in the campaign. Though his active participation in the agitation is unsubstantiated on the first day, Shah confirms his presence on the second day of the burning ceremony of the certificates by the volunteers. According to Shah, many of the volunteers faced deportation, but as decided earlier, “the deportees recrossed the border into the Transvaal without permits and were arrested and given prison terms; six weeks in Mohanlal’s case.”

In the course of tracing her family history, Shah manages to examine a host of other contemporary socio-political issues — the exodus of tradesmen, the predicament of indentured workers, and the haplessness of the politically marginalised — relating their tales of suffering amidst the burgeoning challenges of exploitative colonial capitalism.

It is undeniable that a lot of painstaking research has gone into Shah’s The Other Mohan but notwithstanding the rigours of the writer’s perseverance, the sheer feasibility and scope of the research seem untenable on occasion. Given the historical nature and context of the work, the exploits of Mohanlal, admittedly “an ordinary person” and a peripheral member in one of Gandhi’s satyagrahas, do not consistently sustain the volume. This is evident from his intermittent and prolonged absences from the main course of the narrative. As an inevitable consequence, readers are provided with extraneous details about people and places and the circuitously arduous course of the research work undertaken. Such digressions impinge on the flow and the continuity of the historical analysis, which, at times, has to withstand a good dose of speculative inferences. Also, the minutiae provided on Gandhi’s movements in South Africa have better historical precedents and, thus, fail to add to the novelty of the project.