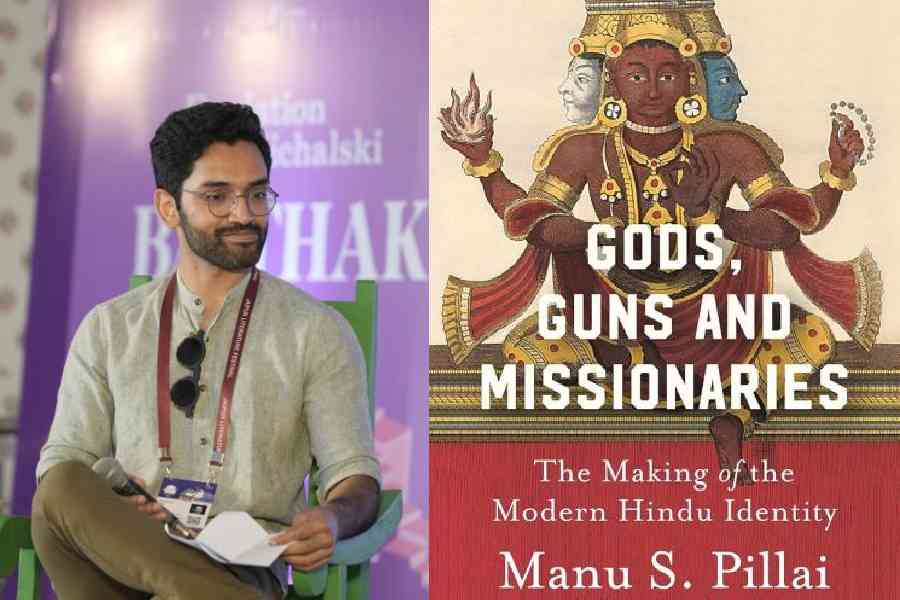

Manu S Pillai, author of The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore, Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji, The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin: Tales from Indian History, and a few more, was in the city for Kolkata Literary Meet with his latest book Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu Identity. He had his fans transfixed during his session with Sujaan Mukherjee. We caught up with the historian who is modernising tales of the epics, for tete-a-tete post his session. Excerpts from the chat.

You talk about Gods, guns and missionaries in the same breath in the title of your new book...

The title was intended to reflect the core themes of the book. It talks about religion, it debates God, therefore, God made sense. The other big element in the book is the missionary and therefore, the missionary makes sense. They were an interesting, diverse group of people who came to India, and there wasn’t just one type. Guns here is a reference to colonials. The interaction is between Hindus and their debates on God, with missionaries who had a very different version of God, which happens in a colonial kind of environment, starting from the Portuguese and ending with the British and their departure from India.

Calcutta connects with all three elements, including missionaries who still have a significant presence in the city.

The missionaries in Calcutta and also South India and elsewhere, were very fascinating. As I said, there were different types of them. Some were very aggressive, some were very understanding, some were creative, some did a lot of research into Indian culture. Of course, they intended to convert but yet their research does have academic value because they did genuinely find a lot of things about India fascinating. So, in fact, reading a lot of missionary literature is often very interesting for someone like me because you can see sometimes the politics of it but sometimes you’re also amazed by how much effort they put into picking up Indian languages, understanding a little of the culture and so on.

The fourth important element of your book is modern Hindu identity.

In the book, I’m talking about modern Hinduism rather than Hindutva, which is just one segment, one chapter towards the end. So, it’s not about Hindutva but it’s about the road to Hindutva, how that road took form. And that form has a lot to do with the modern Hindu identity, how Hindus think of themselves, how we project the religion to outsiders, the contradictions within all of that together makes it a very layered, interesting but also often contradictory kind of dynamics, which I have explored in the book.

The narrative does not come out into the present. It stops with Savarkar and his definition of Hindutva and ultimately Savarkar’s death. It doesn’t come into post-Independence India.

The idea of the book started when you were in college. How did it take shape then onwards?

I have been interested in the idea from the time I was a masters student abroad. I wrote a dissertation on it when I was 21. At 29, I thought, okay, now I need to do a book. I remember in 2020, I did four chapters of the book, and then I went back to the project and finally finished it last year. So it took 12-13 years.

You’re someone who makes history more interesting and you also know how a young mind functions. What is your process or approach to writing, keeping young readers in mind?

Everywhere I go, I see lots of young people. Even at this festival there are so many young people who have showed up. So, they definitely want to know. The question is, how do we engage with them in different formats? So, for example, I do the book, but I also appear on podcasts, I also put out things on Instagram because I don’t expect them to only look at the book. I want them to ultimately come to the book for the details. But I also see it as part of my duty to reach out to larger numbers of people in formats that they are now familiar with. Some people frown on social media because there is a lot of misinformation there but I think social media can also be used to put out good, well-researched history. And people are willing to engage and consume it.

What is it about history that keeps you intrigued and passionate to write one book after another?

I’ve always loved history. Partly because I know for a fact that history is not just textbook history. It has a lot of colour, it has a lot of life, it has a lot of layers, it has contradictions, it has comedy, tragedy, all of those things. So it’s actually a very vibrant, colourful kind of subject to study. The reason most people think history is dull is because of the way it’s taught in school where it’s just a series of dates and events. If you make history about the people in it, about the societies in it, how they engage with different things, that’s where you find people taking an interest.

When you’re not talking about history or reading anything about history, what do you do?

I go to the gym. I actually do. My job requires me to sit at a desk for hours at a time. So the middle of the day is a couple of hours that I get to stretch my legs and move. I’m not one of those introverted people who likes to sit at a desk all day. I like being out, I like having movement.

What’s next?

In my head, I have multiple topics, but for the time being, I’m going to pause because of the promotion for this book. Once that’s done, I intend to take a break for the rest of the year.