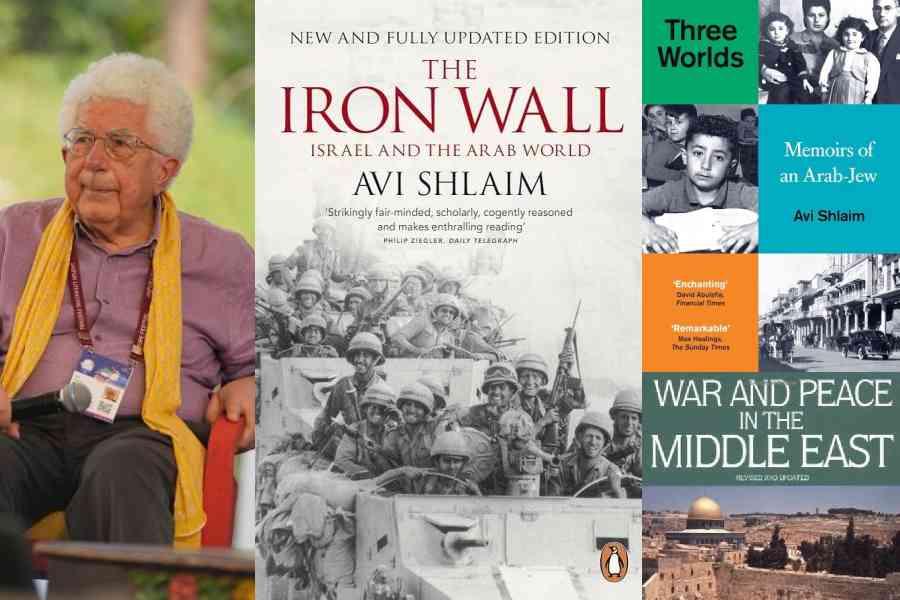

Israeli-British historian Avi Shlaim asserts, “I’m always on the side of the underdog” and “an ever shrinking minority of Israelis”. The Arab-Jew, who was forced to leave Iraq with his family when he was five years old to settle in Israel, is known for his critical views on Israel and the popular Zionist narrative. The septuagenerian who has extensively researched the Arab-Isreal conflict and belongs to Israel’s new historians, has been an Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford. His literary oeuvre includes half a dozen titles that centres around the conflict-ridden themes of the Middle East like Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations (2009), War and Peace in the Middle East: A Concise History (1995); The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (2000) and more. In his latest book, he weaves the personal and the political. However, Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab Jew is not a conventional autobiography; it’s the story of what happened to the Jews of the Arab world. A t2oS tete-a-tete with Shlaim at the Jaipur Literature Festival.

Standing with the underdog

I feel that India is not so alien to me because it’s so multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multi-cultural, and because I am from Israel and Israel is a multicultural society, I could connect with India. However, there is a difference. Israel is no longer a democracy. It is an ethnocracy in which one ethnic group dominates the other. So it’s an apartheid state. And I’m afraid that India, although it’s the largest democracy in the world, has also gone down the sectarian route, and there is a Hindu dominance. Hindu nationalism is the dominant ideology, and there is a lot of intolerance and prejudice against Muslims. I’m always on the side of the underdog. So in Israel-Palestine, I’m on the side of the Palestinians. In India, I’m on the side of the Muslims.

Undeterred new historian

Jews are meant to be very argumentative. There are jokes about two Jews and three opinions. And there is a long tradition of Jewish descent, and I belong to that tradition. Once, a Jewish journalist in Britain criticised my performance at a meeting, at a debate, and she said, being critical of your own side is nothing new. There is Marx and Freud, and she meant it as an insult, but I took it as a huge compliment to be listed against these other Jewish dissidents. In Israel, I was always a minority; I am one of the new historians. We have critical accounts and critical narratives of Zionism and of the state of Israel. But that was okay until recently. What changed everything is the war in Gaza. The Hamas attack and Israel’s violent response to the Hamas attack on October 7. That was a traumatic experience which united all Israelis, left, right and centre. And they all think after that we are justified in doing anything to the Palestinians. So now there is very little descent from the war on Gaza. Many Israelis want the Israeli army to use more force and more destruction in Gaza. I feel now I am in an ever-shrinking minority of Israelis. But that doesn’t deter me from speaking out, speaking truth to power. I have got a book which will be published this month. The title is Genocide in Gaza: Israel’s long war on Palestine.

Because I write critically about Israel, nationalist Israelis don’t like my views. Some have denounced me as a traitor. But I distinguish between serious critics, like academics who have read my books and have criticisms. So, I would engage in a constructive debate with them. And ignorant critics who just think my country is right or wrong and are not open to rational argument, my attitude is simply to ignore them. In the Ottoman Empire, there was a saying, “The dogs bark and the caravan passes”. So the dogs bark — our critics. But the new history — the caravan — passes.

Weaving the personal with the political

I hesitated for 15 years before embarking on Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab Jew. I hesitated because my field is international relations, and so far, I had written a lot about the international relations of the Middle East. I have also written a biography of King Hussein of Jordan. This was easy as there is one central character and everything revolves here. But I have never written about myself. So that was difficult. When I came across a book, a history of the Jews of Iraq, I learned a lot about this community, and this gave me the idea of putting my family story in the wider context of the Jews of Iraq. This book is an attempt to interweave the personal with the political.

My wife read the book chapter by chapter, and when she got to chapter 5, she said, Avi, I am very worried because I am on chapter 5, and you aren’t born yet. And I said to her, this is the whole point of the book. It’s not a conventional autobiography just about me; it’s about the story of what happened to the Jews of Iran. I was just one participant in this historic process. So, in short, I am not an important person, but I lived in important times for the Jewish community in Iraq. As I am a professional historian, I thought it was my duty to record an account of what happened to this wonderful ancient Jewish community in Iraq.

The Zionist narrative

I was lucky in that my mother had a phenomenal memory. And for the four years that I was writing that book, I was talking to her all the time, interviewing her and recording what she told me. So I had a lot of material to write about our life in Iraq. The other issue is that I am at odds with the official Zionist narrative. But then, as a historian, it wasn’t a challenge for me to be writing an account of what happened to the Jews of Iraq and the exodus of the Jews from Iraq to Israel, which was critical of the Zionist narrative. The Zionist narrative says that anti-Semitism was pervasive throughout the Arab world and the Islamic world, and that anti-Semitism drove the Jews out. And I say, no, there was a long history of peaceful coexistence and harmony between Muslims and Jews in the Arab world. The real turning point was the establishment of a Jewish state in 1948, which was a divisive force that divided Jews from Arabs, Israelis from Palestinians, and Muslims from Jews.

Fludity of identity

One thing I learned from writing this book is that identity isn’t a fixed thing. Identity is very fluid; it evolves. We don’t shape our identity on our own. Society shapes our identity. In my case, Israeli society or the Zionist society, wasn’t a benign force. It made me feel inferior. It took me many, many years, until I left Israel and was educated in Britain, to get over the sense of inferiority. When I wrote this book, I realised that having lived in the Arab world, in Iraq, was not a disadvantage. It was an advantage because I relate to Arabs as real people rather than as the enemy. So, my current identity is that of an Arab Jew. And for me, the hyphen in Arab Jew unites rather than divides the Jew from the Arab Jew.