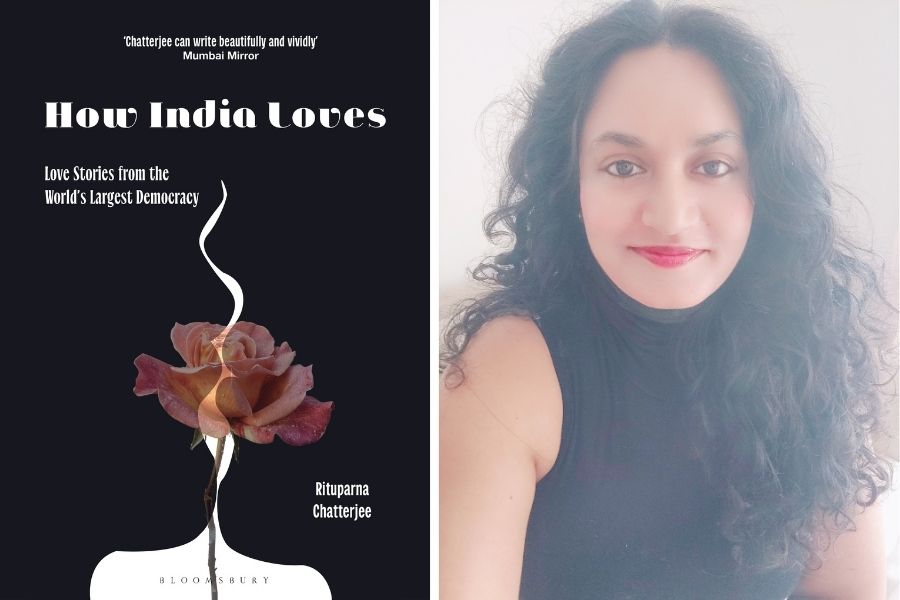

In today’s time, what does love look like in India across different socio-economic stratas? Journalist Rituparna Chatterjee returned to India after 20 years in Silicon Valley. and while touring for her memoir The Water Phoenix, she had various people from all around the country tell her their stories of love, betrayal and resilience. This planted the seed for her recent book, How India Loves — Love Stories from the World’s Largest Democracy, published by Bloomsbury India.

While most would assume Chatterjee has a Kolkata connection, she grew up in Mumbai and married into a Punjabi family, eventually moving to the US. In the following excerpt from the chapter titled ‘Kolkata’ she recounts her experience of witnessing love and woman power in the City of Joy. She finds tales of polyamoury, of violence in love, of quiet resilience and of women supporting each other. In the city of romantics, as she calls it, she finds wronged women and feminism existing side by side.

Kolkata

It took me a while to identify that this infection was what my maids would tell me was the spirit of Kali, Durga, Bengal, a matriarchal state of ferocious warrior women goddesses who took no shit from anyone. The Kolkata air was full of the rage of its wronged women, who were simultaneously hopeless romantics seeking love. I couldn’t tell what was happening. But I wasn’t myself at all in this land of Kali worshippers, where I felt I was being seen for the very first time not as wife, mother, daughter, writer. Of course, I was all these and mostly a woman.

But when everyone from the cobbler and tailor to random millionaires called me Ma, as every girl was addressed as the mother goddess from the day she was born, I got the goosebumps. I had to often rush to cry before I got used to it. It was surreal, the energy. Nowhere in the world have I seen women be so respected and yet so wronged. And the three maids in my father’s house who chatted nonstop helped me comprehend it.

The love stories began pouring in from anywhere and everywhere. They’d have come even if I had locked myself in my room. Even if I was in the hotel bathroom. There was no escaping these stories. That is how I shifted to finally writing about love, sex and relationships in my column for two years and the seed of this book was born, for the stories just would not (and still don’t) stop. The younger ones called me Didi. In fact, between being called Didi and Ma nonstop for slightly over a year, I forgot what my name was. Only my bylines and documents reminded me of it.

A Thailand-style floating market where vegetables were sold on boats parked in a pond, amidst ponds here and there, were a sea of romantic nincompoops. I had to often wade around the boats, poking my way ahead with my giant red umbrella saying, ‘Didi ke jete din (let Didi pass).’ It was a city of lovesick puppies, holding hands, with romantic music blasting out of speakers, even at religious events. Pujo, which really seemed to happen every two weeks, meant nothing got done. This was the city of pujo and prem (worship and love). My maid asked me why I didn’t have a few boyfriends. I reminded her that I was married. It didn’t matter. Apparently, I was the only non-romantic nincompoop around. I had once seen a sole albino seal pup stand out in a giant crowd of resting seals at Pescadero, local to me in the San Francisco Bay Area. In the sea of nincompoops around me, I felt like that seal pup. As in, to the nincompoops – for being romantic, goddess-worshipping, lovestruck nincompoops was normal – I, a logical, work-oriented, monogamous person was the only nincompoop.

In her book, Chatterjee writes, Kolkata is ‘a city of lovesick puppies, holding hands, with romantic music blasting out of speakers, even at religious events’ iStock

It was a city where everyone loved everyone. Polyamory was everywhere, from the streets to the mansions, both crumbling and new, to the glitzy skyscrapers and penthouses that were popping up everywhere, making this ancient city appear more and more like other cities in India, say NCR or Mumbai. Beyond sheer amusement affected me on a daily basis. For instance, I couldn’t get photocopies from any of the three photocopy shops in my neighbourhood. Why? It was always some goddess’ ‘birthday’. Or one of the relatives of the several wives (agreements were more in the heart than on paper, as we will see in the upcoming chapter on polyamory) of the shop owners had to be appeased. I got all of this information from the sweet shop vendor next to one of the photocopy shops. Seeing me so furious at the shops being always closed, he forced me to (for I had said no many times) to eat mishti, which were on the house. How come polyamory did not affect his business? How come the sweet shops were open (barring the traditional afternoon siesta, of course) and professional? The economics of this baffled me, making the business journalist in me itch to dig into the matter of polyamory-induced economics. I had to constantly take Ubers from south Kolkata to the more Marwari-dominated central Kolkata, which had a better work ethic, simply to get photocopies of my documents.

The evenings were the same and very powerful. The sound of conch shells was everywhere every evening. The evening air was filled with the perfumed smoke of incense from shondeh, the evening worship in the households, and the innumerable little neighbourhood temples, most of them of goddess Kali. Offerings included sweets and flowers – most of which in this southern Kolkata neighbourhood were bought from one woman, who turned out to be my father’s maid’s friend, and whom my maid brought over to the house urging that I listen to her story because I was a writer. (Little did I know then that, this being the city of literature, Kolkatans everywhere would keep doing this to me every day for a whole year.)

With her beaming smile sporting missing teeth and framed against her old green cycle-rickshaw filled with colourful flowers, Suprabha is a sight to behold and one that is impossible to forget. Each dawn, at around 4 a.m., she takes a train to Howrah to buy the freshest flowers – hibiscus, marigold, a type of fragrant jasmine called jui phool and rajnigandha (tuberoses) – from the wholesale market. She returns, cooks for her family, finishes her household chores and begins selling these flowers by 9 a.m., returning home only after 1 p.m. for lunch, further chores and tending to her twenty-one-year-old son who has a nerve problem severe enough to cause seizures and which doesn’t allow him to work for very long.

Her husband is a raging alcoholic who beats her as and when he pleases. He has sold off the remaining five cyclerickshaws they had owned to fund his addiction. Just a few days ago, when she had joined her neighbours in a political rally, he had found her there, pulled her thick silver chain off her neck so hard that it broke and left cuts on her neck and her thumb while she tried to shield herself from him. Suprabha is the sole reliable breadwinner of the family. She used to be a maid, but for the past five years she has been making about ₹7,000 a month selling flowers. It means lesser hours at home and freedom from both her violent husband and the tantrums of employers.

The husband constantly stalks her to ensure she is within his control – though for what reason or purpose, nobody knows. But then, violence rarely knows logic. She had filed a first information report (FIR) against him at the Park Circus police station, but after a couple of days of taking him in, the police had let him go. She knows they cannot keep him behind bars forever, which is why she has given up on reaching out to the police for help. Looking at her smile, you cannot tell that she goes through daily hell.

__________________

‘...women in this city were taking up jobs involving physical stress, jobs stereotypically associated with men’ iStock

It was the eve of India’s seventy-fifth year of independence. And all over the streets of Kolkata, I could see a little revolution was on its way – born, of course, out of what else but love stories. Battered, worn out, fuelled by Durga and Kali – the warrior mother goddesses they worshipped – the poor women in this city were taking up jobs involving physical stress, jobs stereotypically associated with men. Women were driving cycle-rickshaws. More and more. Something I had never seen before.

Women were turning into street vendors, selling phuchkas and other street food. Women were now all kinds of street vendors. Pushing carts of vegetables, odd household goods and even conducting repair of old electronics goods. Women were now cobblers . . . and stories (of finding a way out of domestic violence without shirking their responsibilities) like Suprabha’s were all cookie-cutter. Even off the streets, I saw for the first time ever a female salesperson selling heavyduty electronics, like air conditioners and washing machines, helping even in the heavy lifting of these appliances. I had only seen men do this in India.

On the streets at least, many of the women vendors are victims of domestic violence who are empowering and liberating themselves. As India celebrated seventy-five years of independence that year, I could not think of a better celebration than this quiet, unsung revolution in gender dynamics, this feminism, this freedom. But it wasn’t just about the jobs they were doing. It was also about the support they were giving to each other.

My father’s maid Tumpa, who had introduced me to Suprabha (and kept asking me why I didn’t have boyfriends), is a trained Odissi dancer. Tumpa had been wooed by her husband with yellow flowers and a meal at a restaurant in the well-known Acropolis Mall, where he worked as a senior waiter. The same man has turned heavily violent today. If you look closely at Tumpa’s face, you can see the scars from stitches she needed to get done after he hit her. She works as a maid and has a three-year-old who suffers from thalassemia and needs constant blood transfusions.

Fortunately, her in-laws threw their own son out of the house to take care of her and her child. They even helped her file an FIR against him and file for a divorce too so they could organise her marriage to a good man who would deserve her as and when she felt ready for it. They tried to keep her safe by keeping him away from her. But he kept coming back. Tumpa kept saying she would leave him as we had offered her our place to stay in. I had helped her open a bank account too. But I was informed by the security guard of our building that she was meeting her ex who was there with his ex, which she confirmed to me. You see, romance trumped violence. The mother-in-law of another maid, Chanda, also kicked out her violent son, fed up with his violence towards her daughter-in-law. The mother-in-law and Chanda live together in peace, leading a comfortable life from their collective monthly income of about ₹25,000, ensuring that Chanda’s twelve-year-old child has a good education.

Where in the world do mothers kick out their own sons to support the bahu? This kind of open support to the daughter-in-law, of choosing her over a violent, abusive son, their own blood, is perhaps what makes Bengal so unique. It is frankly unimaginable in many of the northern states, where the son is worshipped as a god, no matter what he does. I was married into a Punjabi family, and being familiar with the patriarchy of the north, I couldn’t even imagine such a thing happening there. Nor in America, with its nuclear families.

In spite of the violence against women in Bengal, there is a respect here for women so commonplace that it takes a foreigner to notice how precious it is. The gentle sing-song versions of Ma (and Didi) I am constantly addressed as in this land of Kali worshippers gave me a freedom I had never known before – to be seen as a woman without roles and labels for the very first time in my life.