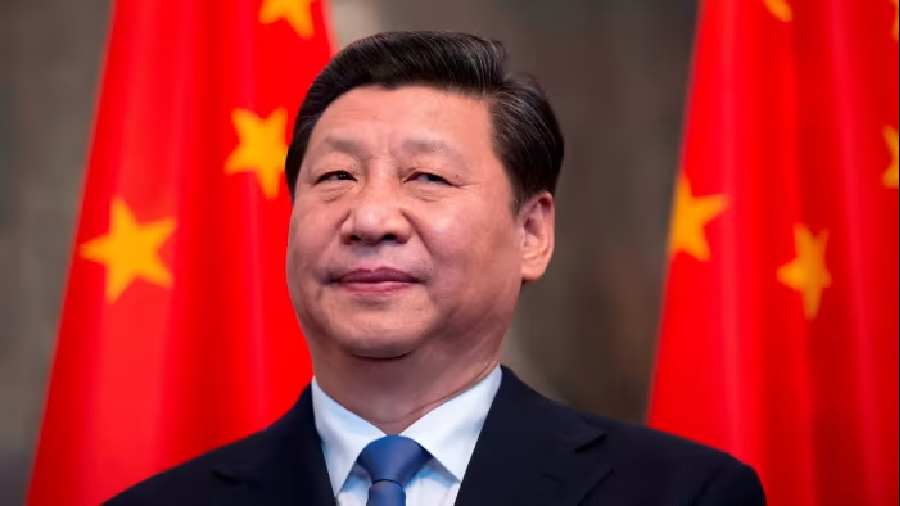

As Xi Jinping, China’s leader, visited Central Asian countries this week, he stepped off planes to rousing performances by rows of dancers, musicians and ceremonial guards. Uzbekistan’s leader called him “the greatest statesman”, Chinese state media declared, while the leader of Turkmenistan praised his “wise leadership”. They draped him in medals.

For Beijing, the pomp and fanfare that greeted Xi, as well as the effusive rhetoric of his counterparts, served to show that China is not isolated despite coming under pressure from the US and much of the West for its human rights violations and threats to Taiwan. In the narrative presented by Beijing, Xi is the reliable global leader that other countries look to for support in a world made turbulent by American hegemony. Even Vladimir V. Putin, Russia’s autocratic leader, seemed almost deferential in his meeting with Xi on Thursday, acknowledging that China had “questions and concerns” about Russia’s war in Ukraine.

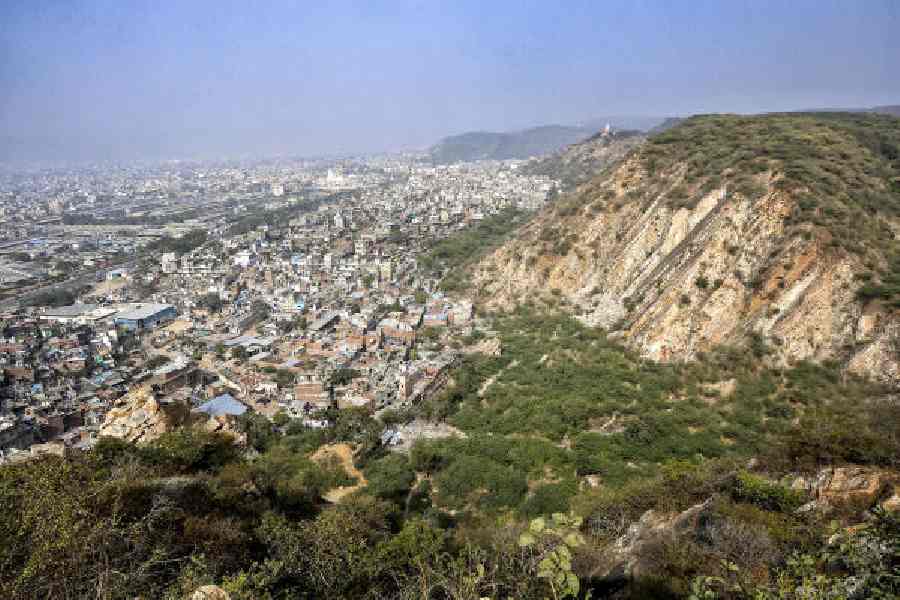

But the pageantry also demonstrated China’s growing sway in Central Asia — a vast, resource-rich region of mountains and steppe once considered Russia’s domain, where great powers have long vied for influence.

In Xi’s meetings with several Central Asian leaders, they were quoted as using phrases and political slogans coined by the Chinese Communist Party, praising him for “building a moderately prosperous society” and advancing towards China’s “great rejuvenation”.

The image China’s propaganda outlets are cultivating is partly an exaggeration. Uzbekistan’s leader, in presenting Xi with an award, had expressed respect for him “as a statesman”, according to the President’s website, and not “the greatest statesman”. Many Central Asian nations welcome Chinese investment but are wary of becoming dependent on Beijing. In countries like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, people share linguistic, cultural and in some cases family ties with groups in Xinjiang, a region in China’s far west. Many have been concerned about the vast crackdown there that has ensnared Central Asian people.

Beijing has long seen Central Asia as a critical frontier for the country’s trade expansion, energy security, ethnic stability and military defence. China has built railroads, highways and energy pipelines and expanded educational exchanges throughout the region.

While the former Soviet republics of Central Asia are still connected to Moscow by roads, rail lines and other infrastructure, their trade is now increasingly with China. The end of the American military presence in Afghanistan last year reduced the role of the US as a geopolitical counterweight to Moscow and Beijing. Putin’s subsequent invasion of Ukraine, followed by a series of humiliating defeats of the Russian army, may give Beijing room to gain an edge.

One complication for Xi’s ambitions in the region is his alignment and personal bond with Putin, the Russian leader whose invasion of Ukraine drew unease in the region. Xi has often described Putin as his “best friend”. On Thursday, Xi appeared to distance himself, at least in public, saying nothing about Moscow’s position on Ukraine and offering reassurances to Central Asian leaders that China would support their sovereignty.

“These are resource-rich countries, relatively sparsely populated, and if Putin’s grip on them weakens, China has been clever and opportunistic,” said Harry Broadman, a former American trade official and a World Bank specialist in Central Asia and China.

The region is familiar with walking a tightrope between powers. The Great Game, a term popularised by Rudyard Kipling, was the 19th-century competition between Russia and Britain for control over Central Asia. Russia’s influence peaked in 1979, with the Soviet military occupation of Afghanistan, then waned with the break-up of the Soviet Union 12 years later.

In what has become a new version of the Great Game, China, with nine times the population of Russia and 10 times as large an economy, has also long been viewed with wariness in Central Asia. Countries there have responded over the years with stringent limits on immigration from China and other measures. They have also sought investment from the US.

New York Times News Service