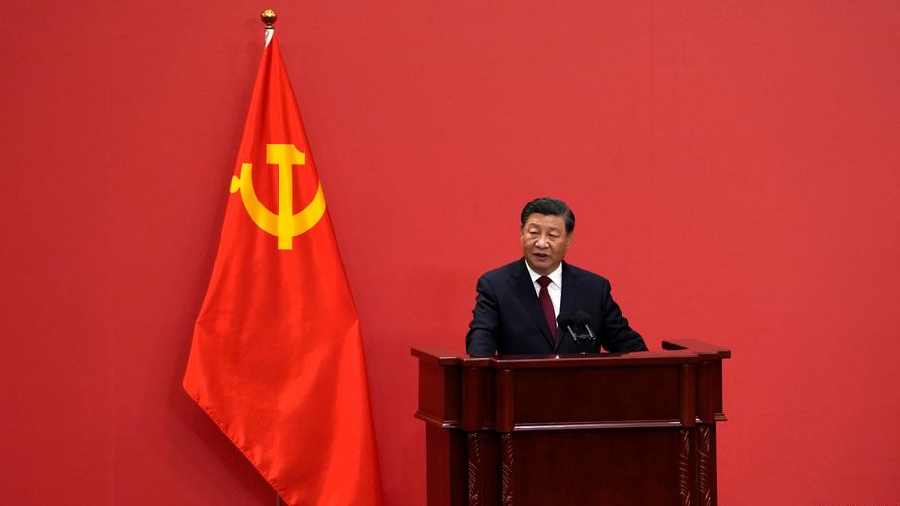

As China’s leader Xi Jinping laid out his priorities this week for a breakthrough third term in power, officials parsed his words for signs of where the country was headed. What he did not say was as revealing.

The omission of two phrases from his key report to a Communist Party congress exposed his anxieties about an increasingly volatile world where Washington is contesting China’s ascent as an authoritarian superpower.

For two decades, successive Chinese leaders had declared at the congress that the country was in a “period of important strategic opportunity”, implying that China faced no imminent risk of major conflict and could focus more on economic growth.

For even longer, leaders had said that “peace and development remain the themes of the era”, suggesting that whatever may be going wrong in the world, the grand trends were on China’s side.

But the two slogans, so unvarying that they rarely drew attention, were not in Xi’s report to the congress, which began last Sunday and ended on Saturday. Not in his 104-minute speech summarising the report. Nor in the 72-page Chinese full version given to officials and journalists.

Their exclusion, and Xi’s sombre warning of “dangerous storms” on the horizon, indicated that he believed international hazards had worsened, especially since the start of the war in Ukraine in February, several experts said.

Xi, who was re-elected on Sunday as party general secretary, sees a world made more treacherous by American support for the disputed island of Taiwan, Chinese vulnerability to technology “choke points”, and the plans of western-led alliances to increase their military presence around Asia.

“China’s external environment now can be described as unprecedentedly perilous, and that’s also the judgement of China’s high echelon,” Hu Wei, a foreign policy scholar in Shanghai, said in an interview.

In the Communist Party, the leader’s words matter enormously, shaping China’s policies, legislation and diplomacy. And the report to the party congress, every five years, is the fundamental guide for officials. Each phrase, each tweak, each omission is weighed to signal priorities.

In his report, Xi said several times that China intended to contribute more to global peace and development through its own initiatives, and discussed “strategic opportunities” for trade and diplomatic gains. But his assessment of global trends was laced with warnings.

“Our country has entered a period when strategic opportunity coexists with risks and challenges, and uncertainties and unforeseen factors are rising,” Xi said. Although China has room for international growth and initiative, he added, “the world has entered a period of turbulence and transformation”.

“This marks a meaningful, and perhaps major, shift in their assessment of the global order,” said Christopher K. Johnson, president of the China Strategies Group and a former CIA analyst of Chinese politics. “He’s basically hardening the system because the likelihood of conflict is going up.”

The party is promoting Xi as the nation’s “navigator” for the intensifying threats.

Xi’s report also represented another step in jettisoning language and assumptions from China’s era of market changes and friendly diplomacy with the West.

The phrase that “peace and development” were era-defining themes took hold in the 1980s, when Deng Xiaoping’s generation of leaders introduced economic liberalisation and fostered ties with Washington, Tokyo and other former foes, said Yong Deng, a political science professor at the US Naval Academy.

It implied that China “had the permissible international environment to focus on modernisations through reforms and opening”, he said, noting that he did not speak for the navy.

Another leader, Jiang Zemin, first declared in 2002 that China could enjoy about two decades of “strategic opportunity” — free of serious risk of major conflict — soon after he had won the country’s entry into the World Trade Organisation. It was a time of expanding commerce and hopes abroad that China would increasingly liberalise, in politics as well as business. Beijing encouraged talk of China’s “peaceful rise”.

Xi’s worries about external risks appeared to come to head in the first half of 2022, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Nato’s galvanisation to support Kyiv, an examination of Chinese officials’ speeches and policy documents indicates.

The war in Ukraine, global tensions over the coronavirus pandemic and Washington’s tough approach to Beijing intensified debate in China about whether it still had a “period of strategic opportunity”, said Wang, who recently published a paper on the issue.

“The impact from Russia-Ukraine was that it was a rehearsal for US containment of China,” Wang said, reflecting a widespread view in China.

“While some of China’s responses to growing challenges were no doubt already under way before the congress,” said David Gitter, president of the Center for Advanced China Research, “the dropping of the terms noted will inject new impetus and assertiveness in a way visible from outside China.”