Tagore’s view of the cosmos was the centre around which the programme of The Tagore Centre for Natural Sciences and Philosophy orbited at Rabindra Tirtha last Friday.

The invitation card carried a quotation from Tagore: “Ami bigyaner sadhok noi shey kotha bola bahulyo kintu balyakal theke bigyaner rosh aashwadoney amar lobher onto chhilo na. (It would be a waste of words to say that I am no votary of science but since childhood I have hankered after the taste of science.)”

Tagore’s childhood years and the influences around him are what Saumitra Chatterjee traced in his speech on the occasion, right from the medical college student who came to teach the boys anatomy. “Tagore’s third eldest brother Hemendranath, who was responsible for his home-schooling, had written a book in 1873 titled Prakritik Bigyaner Sthul Mormo (The Basic Meaning of Nature Sciences). Years after his death in 1897, his son Kshitindranath got it published. Tagore’s elder brother Dwijendranath was a mathematician of uncommon calibre and had worked to rectify the faults in Euclid’s geometrical theories.”

Chatterjee felt that the seeds of modernity in the Tagore household was sown through the lifestyle of Tagore’s grandfather Dwarkanath who introduced society to European thoughts, machines and technology. His son Debendranath, though dedicated to spirituality, in spurning age-old idolatry had embraced a more contemporary thought process and inspired in Tagore a search for truth and knowledge.

The necessity of scientific knowledge was being felt at that time. Rammohun Roy suggested a science syllabus while Vidyasagar proposed to teach Francis Bacon in school though the British and their native bureaucrats did not accept either suggestion.

If Tagore’s passion was systematising Bengali language and spelling, he was also concerned about creating scientific terminology. His scientific writings that started at the age of 13 culminated in the book Biswaparichoy, written at the age of 76, for the purpose of public awareness. His interest in the life and physical sciences was deepened through his friendship with Acharya Jagadis Chandra Bose.

Having travelled to Europe at a young age, he had realised that the core of the western civilisation was science. So when he set up a school in Bolpur in 1901 at the age of 40, he declared that “steam and electricity” shall “become our nerve and muscle” (in Sadhana), highlighting his resolve to embrace technology alongside a cohabitation with Nature as practised in ancient times. His mud hut Shyamali is an example of the latter. The traditional festivals he celebrated at Santiniketan and Sriniketan — Basanta Utsav in spring, Halakarshan in monsoon, Poush Mela in winter —were linked to the cycle of seasons rather than to specific religions.

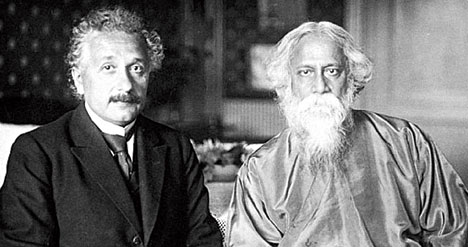

In 1930 itself, Tagore met Albert Einstein four times. How updated he kept himself, Chatterjee says, is proved by the allusion in Biswaparichoy to a discovery as recent (in 1932 by James Chadwick and Carl Anderson respectively) as neutron and positron in the 1937 publication by the septuagenarian poet who spent five years on the scientific treatise.

Nuclear physicist Dipak Ghosh demonstrated how different emotions are triggered by different applications of musical notes using hard science tools like EEG. “This is something Tagore had wanted to know.”

Tagore, Ghosh said, had emphasised the role of the individual in sensing Creation and expressing its manifestation. ‘Ether trembles, I see light; waves form in air, I hear sound; the minutest dissected atoms are involved in action and reaction, I see a big undissected object (translated),’ he had written,” quoted Ghosh. This belief also comes through in his conversation with Einstein. When the scientist asks if he believed in the Divine as isolated from the world the poet replies in the negative, explaining that “the Truth of the Universe is human Truth” and is “realised through Man”.

His poem Ami, starting with Amar-i chetonar rongey panna holo sobuj… is an expression of that belief.

“Our research on neurocognition of music shows how neurons tremble in a specific rhythm on listening to a pattern of sound. The rhythm of the neurons changes if the pattern does,” he said, playing the sound achieved by sonification of the rhythm of the neurons on listening to specific Tagore songs of varying moods and tempo. Ghosh’s talk was accompanied by songs reflecting Tagore’s view of the cosmos by Archi Banerjee from the Sir CV Raman Centre for Physics and Music at Jadavpur University where Ghosh is an emeritus professor.

Pandit Ajoy Chakraborty took the stage at the end. He contended that Tagore had understood that the grammar of a raga could not limit its success. “That is why in a song like Anandadhara bohichhey bhubane he uses some notes not expected in Malkosh. But now his songs have become too notation-based.”

The notations, he insisted, could not be the ultimate decider for a performance. “The tempo, for example, is not indicated in any Rabindrasangeet notation. How would it sound if I sing these songs like this?” singing Khara bayu boy bege slowly and Ei korechho bhalo in a fast tempo.

Former Visva Bharati vice-chancellor Sushanta Dutta Gupta, a resident of Uniworld City, offered the vote of thanks. “The three speakers spoke about three facets of Tagore’s science consciousness,” he said. Substantiating one of Chakraborty’s contentions, he quoted Tagore’s letter dated January 6, 1935, to Indira Devi Chowdhurani, who wrote the notations of many of his songs, saying that it was better not to mention the raga of a song.

“He also wrote to Dilip Kumar Roy, arguing that his songs were different from Hindusthani songs.” “The tune of Bengali songs searches for lyrics… It succeeds when in unison with the lyrics. The development of Bengali music does not follow the tradition of Hindusthani songs. A palm tree should not be burdened with the roots of a banyan tree,” Dutta Gupta said, quoting Tagore’s letter to Roy.

The centre, said Bikash Sinha, the president of the centre’s governing council, was born four years ago. “Our office was at first in Bose Institute. Now we are housed in Rabindra Tirtha,” the physicist said.