|

|

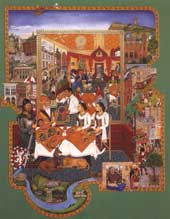

| (Clockwise from above) A detail from Mr Singh's India, The Last Supper: Dedicated to Cha-cha Baldave, A Brave and Noble Soul and Painting The Town Red |

The Singh Twins of Liverpool use Mughal miniature traditions to suit their own ends. Soumitra Das reports on their show at CIMA Gallery

can one expect to see nothing better than these milk-and-water Mses of the Facets of Femininity series by the identical Singh Twins of Liverpool that one encounters on entering CIMA Gallery, where their exhibition Past Modern opened on Thursday evening? Never mind the arcane symbolism of flora, fauna and heraldry, Marylin Monroe flashing what she pronounced were a girl’s best friends, the religiosity of Mother Teresa and Madonna’s bustier depicted in the meticulous style of Indian miniature artists of yore is not really an updated version of the traditional Mughal style, the style Amrit and Rabindra K.D. Kaur Singh declare they have adapted in Alone Together Shakila Maan’s film on them.

Hopes belied by the punning title of the exhibition presented by the National Gallery of Modern Art in collaboration with British Council, the preachy, wannabe campy depictions of sports icons such as Venus Williams, too, fail to stir up one’s flagging interest.

Then suddenly round the corner, one is confronted with this splash of vivid colours in turmoil and a gallimaufry of intricate details of life as lived by Indians in multicultural Britain in all its rambunctious, raucous and rampant exuberance and vulgarity.

This must have been the strategy of the identical Singh Twins, who never have a hair out of place and look prim and proper in their carefully pressed salwar suits -- to attack the sense and sensibilities of viewers when they least expect it. Like latter-day Jane Austens, they look and behave like any other Sikh women of their class. But what they have up their sleeve is a different matter altogether.

This is most obvious in the series of three paintings, Daddy in Sitting Room. The first shows a man in a conventional “Western” setting. With each successive painting the interiors become increasingly and deliriously “Indian.” In the final work, riotously coloured and patterned elephants have invaded the room and the gigantic visage of a Hindu deity occupies the ceiling.

The Singh Twins were trained in art at Liverpool University College but they went back to their Asian roots, their “heritage” for inspiration. Even as they revisit tradition they cannot help cocking a snook at it. As seen in the film, both work together, poring over a painting being executed with the patience of a lapidary artist, making variations in a sketch in keeping with the other’s suggestion. It must have taken them hours of hard labour to create each painting that resembles calendar art as executed by a miniature painter — kitsch parading as high art and the reverse.

Unlike the miniature artists who were, as far as we know, mostly male, the Singh Twins make full use of their feminine sense of colour and design. Using poster colours or gouache the human figures are caught against a rich backdrop of Oriental pattern that looks like linoleum displayed in a shop window. The eye is allowed to wander from detail to detail that reveal the contradictions inherent in the culture of the Indian diaspora – the snowman that looks like a sardarji, the Sikh participants of the Tall Ships Festival in Painting the Town Red, the Mocha print, portrait of Sikh guru and Madonna all vying for attention in the same room.

Each painting seems to tell a story, the eye wondering along the geometric structure of a work. Pitha ji in ceremonial garb begins life in Amritsar and ends up as a graybeard who admires both Mother India and King Kong. And thereby hangs a tale.