|

|

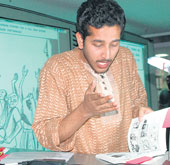

| Actor Parambrata Chatterjee reads from The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers at its launch at the British Council. (Below) Sarnath Banerjee. Pictures by Sanat Kumar Sinha and Sanjoy Chattopadhyaya |

Sarnath Banerjee’s response to his latest work is ambiguous. There are “incidents from my own life”, but it is not “autobiographical”. “People think I have an obsessive compulsive disorder with Calcutta,” says Sarnath, the pin-up boy of the graphic novel in India.

The city is the centre of his second book, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, which dips into the decadence of 18th Century Calcutta seen through the eyes of Abravanel Ben Obadiah Ben Aharon Kabariti, a wandering Jew prototype who calls himself the Owl.

Three years after he began, Sarnath, is certain of never spending as much time on another Calcutta novel. “This was my Calcutta book.”

Sarnath loves old cities. “The ghost of one city lives in another. There are bits of Calcutta in Paris and London. My book was an attempt to explore the psychic core of Calcutta,” he says. Sexual proclivities lie at the heart of the novel, which the writer explains as: “Let us celebrate the repression.” He promises his next novel will be more graphic, sexually.

Much of the city’s history is still preserved in its alleyways, he feels, “but we seem not to care about it”. Mumbai, according to him, is an over-articulated city, with its self-conscious image-building, but Calcutta allows itself to be passed by.

His relationship with the city is ambiguous. “To write about Calcutta, I had to go away from it, though it would have been more convenient to be in the vicinity.” Calcuttans like Digital Dutta and Kedar Babu, who resemble stereotypes of the armchair traveller, are close to him — the latter, a self-styled psychic cartographer, who, though a government clerk, tries to go beyond the humdrum of daily living. Dutta travels in his mind.

“When I was growing up, it was believed to be a miraculous world beyond the borders of the country. When I went to study in London, I realised that much of the wonder of bilet was a myth. Digital Dutta shares that fascination as a child of the 1970s. The western concept of travel glorifies the educative aspect of it, while playing down the economics.”

Sarnath calls his novel factification. “It is manufactured history. It starts from truth, and goes beyond. And history itself is often a bunch of lies, distorted by perspective.” Researching at the British Museum in London for a year-and-a-half, he realised that it would be fun to subvert history. So, he went looking for the style of Lord Hastings’s night attire, “though the reader might not notice it”.

His Calcutta research was mostly culled from the streets of Shyambazar and Beadon Street, where the Battala industry thrived. There are suggestions that he lifted entire sections from Kaliprasanna Sinha’s book Hutom Pyanchar Noksha. “I have grown up listening to stories of old Calcutta. For me, it lives in the oral culture of that part of the city,” counters Sarnath.

The graphic novel is still in a nascent in India, and Sarnath jokingly refers to his publishing house, Phantomville, as a retirement plan for himself and partner Anindya Roy. For now, he lives in Stuttgart, writing a set of 21 three-minute operas for the Baden Wurtenberg opera house.

Calcutta lives as a delicately balanced state of mind: “You can’t regress into nostalgia. But it is sad to see the flurry to catch up with the rest of the world.”