Teachers in Bengal aren't as sincere in teaching as they are about demanding a pay hike, academician and poet Shankha Ghosh said on Sunday.

Ghosh, who has taught Bengali at several institutes, including City College and Jadavpur University from where he retired in 1992, said lack of accountability in terms of quality of teaching was a "form of corruption" that had led to the decline in the standard of education in Bengal.

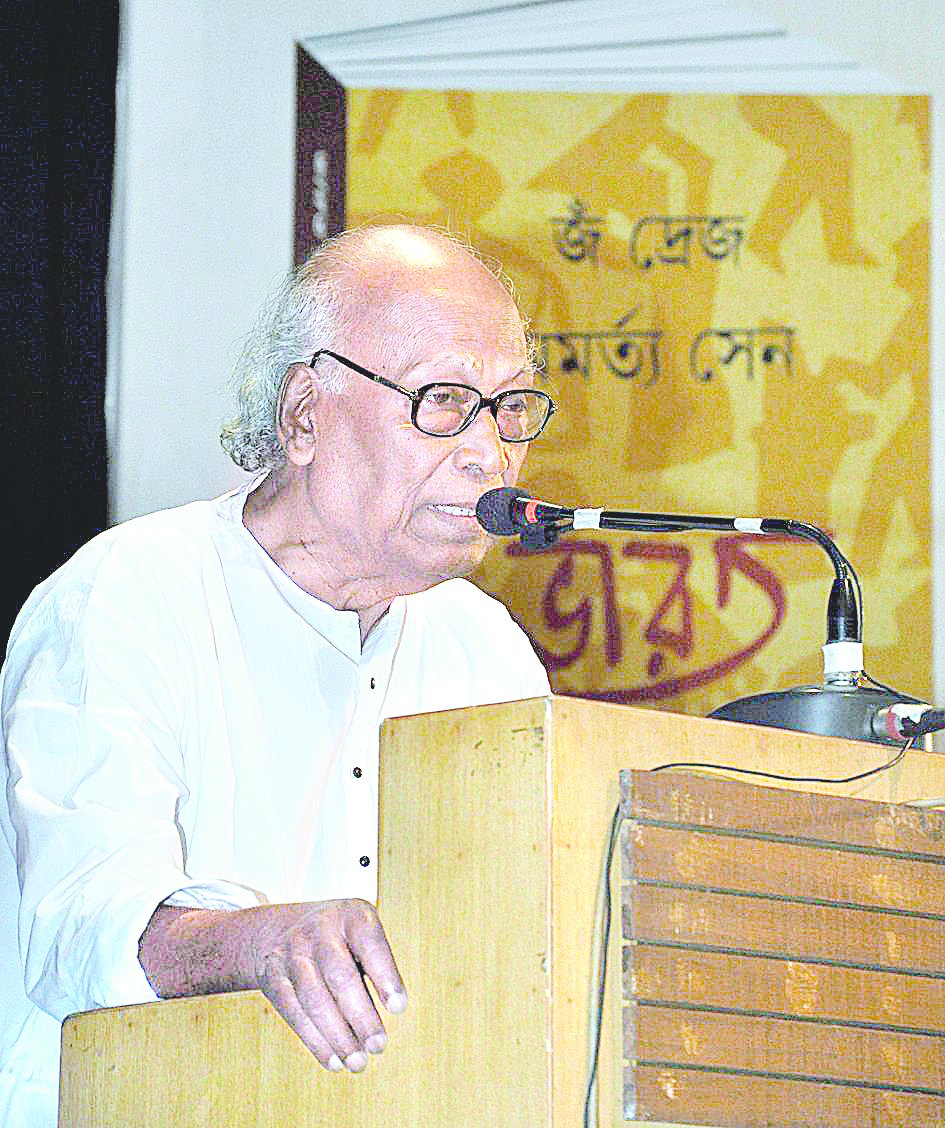

"I saw teachers protesting against poor pay in the late Fifties. The agitation was legitimate as the salary was then abysmally low. But I also noticed that we weren't too interested in doing our job. We still aren't serious about taking classes. We skip classes frequently, yet we demand a hike in salary. This lack of accountability is a form of corruption," Ghosh said at the launch of Bharat: Unnayan O Banchana, the Bengali translation of An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions, by Jean Dreze & Amartya Sen .

Teachers' pay has improved over the years but they haven't become more sincere in taking classes, Ghosh told Metro later.

"This goes to show that the hike in salary does not guarantee proportionate performance by a teacher. A chapter of the book (by Dreze and Sen) states that a jump in salary doesn't ensure better performance. On the contrary, the performance is disproportionate to the increase in pay," Ghosh said.

Sugata Bose, the Lok Sabha MP, Harvard University professor and chief mentor of Presidency University , said "absenteeism" by teachers was one of the problems plaguing education.

"In institutes where I have taught and continue to teach, like Tufts University and Harvard, I haven't noticed the problem Shankhababu referred to. As for me, I still take extreme care in terms of preparation before attending my next class or delivering a lecture in a seminar. The question of skipping class doesn't arise," Bose said.

During a student agitation at Jadavpur University last year, a section of teachers had supported the call for an academic boycott and stayed away from classrooms for a couple of weeks. "As a teacher, the biggest concern for me this evening should be how I can charge myself up for an even better lecture in class tomorrow. But I don't see that in many teachers at JU," a former vice-chancellor of JU had said during an interview with The Telegraph in January.

Sukanta Chaudhuri, emeritus professor at JU, too had once said that teachers in Bengal weren't as serious about demanding better infrastructure in their institutions as they were about getting a pay hike.

"I am sure had they been as serious about improvement of infrastructure of their institutions..., some steps would have been taken to solve the problem," he told a programme organised by the West Bengal College and University Teachers' Association in 2013.

"Most of us are aware of the poor infrastructure in many colleges. But how many times have teachers' bodies like this organisation raised this issue for discussion?" Chaudhuri said.

Subrata Pal, a professor of life science and biotechnology at JU and former vice-chancellor of Burdwan University, said: "An academic boycott can't be justified. It is the primary duty of any teacher in a state university funded with public money to take classes."

The Mamata Banerjee government had issued a circular in 2012 specifying the minimum number of classes a teacher should take in a week. The government made it mandatory for teachers across 450 state-aided colleges to put in a minimum of five hours daily, six days a week.

The rule was never enforced, an official said.