|

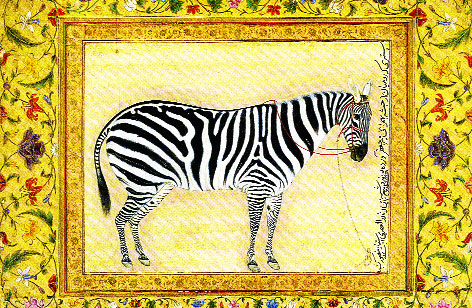

| A zebra inscribed by Jahangir, as drawn by Mansur, from Asok Kumar Das’s book |

One may not know Ustad Mansur, the Mughal court painter, by name but one may nonetheless be familiar with his miniatures of the opalescent chameleon leering at a scrumptious butterfly, the zebra and the turkey cock. Mansur began his career as an assistant painter during the last years of Akbar’s rule, and because of his enormous talents it did not take him long to become Jahangir’s favourite. Little is known about the personal life of Mansur, famous for his naturalistic studies of birds, beasts and flowers and depictions of court scenes.

Art historian Asok Kumar Das’s insightful new book titled Wonders of Nature: Ustad Mansur at the Mughal Court, a Marg publication, however, brings alive the works of this master whose hallmark was the animated portrayal of fauna and sensitive and accurate delineation of flora in which his patron-emperor took intense and scientific interest like Babur. It is written in simple prose that has no place for pretensions and intimidating jargon. The excellent colour reproductions of innumerable paintings enhance the value of this work.

The book is the fruit of several decades of dedication and research by Das, who has won some of the most prestigious fellowships such as the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship, Hart Fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, Getty Museum Fellowship (Los Angeles) in 2008, and the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2009-11.

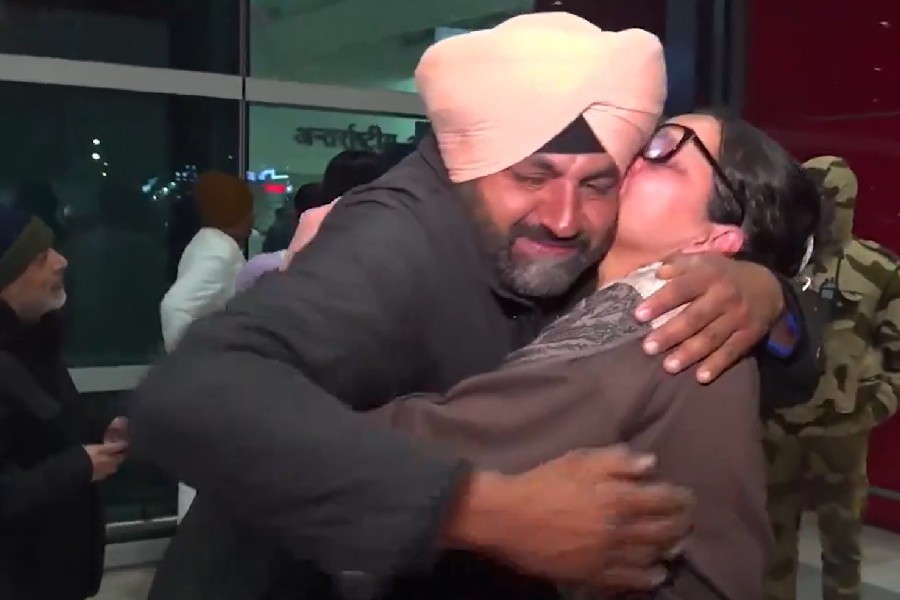

His first encounter with Mansur was at the Indian Museum, where two of his paintings of the Siberian crane and a Bengal Florican were on display at the old art gallery. As he writes in the preface: “I have lived with Ustad Mansur for almost half a century, ever since my eyes first alighted on two extraordinary pictures of birds displayed in the old art gallery of the Indian Museum, Calcutta, on the day I started working there.” Das, who is now Tagore National Fellow at the same institution, has doggedly followed the Mansur trail throughout his illustrious career, during the course of which he has served at museums and educational institutions of international repute here and in the West. His quest brought him close to ornithologist Salim Ali with whom he compared notes.

|

| Asok Das at the Indian Museum. (Sanjoy Ghosh) |

Das continues to narrate in the preface how he encountered Mansur’s paintings at various institutions in the UK, the US, France, Jaipur (he was director of the City Palace Museum, which houses Akbar’s personal copies of the Razmnama and Ramayana manuscripts, from 1972 to 1988), Tehran, Russia and through a vast and wide network of scholars from all over the world who sent him images and additional information based on latest research. In between, Das has written several volumes like Mughal Painting during Jahangir’s Time published by Asiatic Society and Dawn of Mughal Painting, Splendour of Mughal Painting, Mughal Masters: Further Studies and Paintings of the Razmnama.

Das, who was born in 1938, is from Garbeta in Midnapore where he went to school. Subsequently he did his MA in ancient Indian history and culture, and museology at Calcutta University, when he studied under many illustrious scholars, and his PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London on a Commonwealth scholarship.

“I always wanted to be a teacher and it was only pure chance that I had switched over to art history,” says the soft-spoken, diminutive man, who looks every inch the teacher in his striped shirt and corduroy trousers (he only got a chance to teach at a later stage of his life, as Satyajit Ray Chair at Visva-Bharati, and as a visiting professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University). In 1963, he landed the job of deputy keeper (art) at the Indian Museum. He had to work on the first and second floors of the building dedicated to paintings, textiles and the decorative arts. “In those days art history was not taught here, but since I was in charge of that section, I could not justify my position unless I had some knowledge of art and crafts,” says Das.

Das studied Mughal paintings because the Indian Museum has a well-known collection, and, importantly for him, he was following in the footsteps of three great scholars —Ernest Binfield Havell, the principal of the Government School of Art, Abanindranath Tagore and Percy Brown.

“At the interview for the Commonwealth scholarship, I declared that if I was selected I would study Mughal painting. All the best manuscripts and paintings were available at the British Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, Bodleian Library in Oxford, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. More than 60 per cent Mughal paintings are abroad.” And abroad he went.

India has only a few important manuscripts — Timurnama at the Khuda Baksh Library in Patna; Raza Library in Rampur has three important manuscripts — Diwan of Hafiz, Jami ut-Tawarikh and Sirr Al-Maktum, a work on talismans and omens; the National Museum possesses Baburnama and Amir Khusraw’s Ashiqa and Bharat Kala Bhavan has Anwar e-Suhayli, which is a rendering in Persian of the Panchatantra. The rest are all abroad, says Das.

Asked how we know the names of Mughal painters in a country where most traditional artists are anonymous, Das says: “Akbar introduced a system whereby the names of the principal painters as well as those that assisted him are written on the margin of the paintings. We know the names of all the major Mughal painters. Most paintings bear either signatures or ascriptions.”