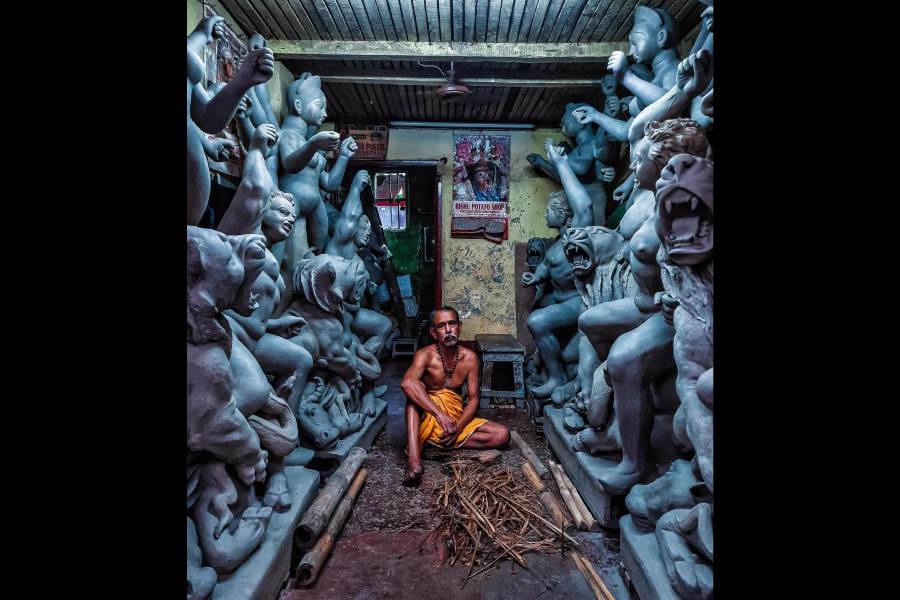

On a rainy August afternoon, Kumartuli — the idolmakers’ enclave in north Calcutta — hummed with the chatter of artisans from various districts.

With Durga Puja barely a month away, all were hard at work, racing against time to ready the clay idols.

Kumartuli, a hotspot for visitors taking photos and selfies to post on social media, has quietly become a hub of intrastate migrants.

Every year, hundreds of idolmakers from remote corners of Bengal arrive here for at least three months before Durga Puja.

“These Durgas give us new dresses for our Lakshmis (daughters) at home. We migrate to this noisy city, leaving behind our loved ones for a few months, to earn an income that makes up half of our annual family expenses,” said Kartik Pal, a 45-year-old artisan from Nabadwip in Nadia.

According to a state government source, Kumartuli — the oldest idolmaking cluster in the city — sells idols worth ₹150–200 crore during the festive season, which begins with Durga Puja and ends with Kali Puja or Diwali.

Like Pal, hundreds of artisans and workers from towns and villages across Bengal take up roles that keep Kumartuli’s lanes alive and buzzing — the skilled craftsman shaping clay, the young hand hauling bamboo frames, the transporter guiding idols to pandals. Together, they form the unseen backbone of the mega festival.

Apprentice to an idolmaker, Kamal Saha, 18, from Notunhat in East Burdwan, earns between ₹300 and ₹500 a day, as he is still learning the craft.

At a time when thousands of unskilled workers migrate to other states for better wages, Saha prefers to stay closer home. “I worked as a trainee idolmaker in Odisha, where the pay was better than here in Kumartuli. However, Calcutta is our beloved city, and I feel safer here despite lower wages,” said Saha, who dreams of becoming a master idolmaker in a few years.

One of his co-workers, busy giving finishing touches to an idol’s hands, added, “Here the dialects may differ, but everyone speaks the same language — Bengali. It always feels like home, even though I stay over 200km away from my family.”

Pal, an experienced hand, earns much more than Saha — ₹1,000 a day.

Working in Kumartuli since his father’s time, Pal said that although he spent a few years in Madhya Pradesh — earning double in cities like Bhopal and Indore — he eventually returned.

The income from Kumartuli is not enough for most migrant artisans. During the off-season, many return to their villages to work as farmhands, daily wage labourers or small traders. Many stay on in Calcutta to take up odd jobs like painting signboards, assisting in construction or working in markets.

But Pal has no regrets. “Here, at least, I can return home quickly if there’s an emergency,” he said.