The popular excitement about a raging war, often without comprehending the pain it carries, was evident in Calcutta even 54 years ago when the city witnessed a war close to it, veteran author Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay said.

Many Calcuttans wanted to go to the border to witness the India-Pakistan war of December 1971 being fought on the eastern front. They had to be told that such an act could be dangerous.

People were glued to their radios for news bulletins as they wanted to know the latest from the battlefield. TV news had yet to arrive. Such was the appetite for information that listeners waited for All India Radio bulletins.

Daily life was impacted as there were blackouts every evening. Street lights were covered, and two-thirds of headlights of cars and buses were blackened. Sirens at factories, used to denote changes in shifts, became silent.

“There was a lot of excitement among people in general about the war. Some people wanted to go to the border to witness the war. The authorities had to announce that no one should go anywhere near the battlefield, because it could be very dangerous for them,” Mukhopadhyay told The Telegraph on Saturday.

The war lasted a little less than two weeks, writes Ramachandra Guha in India After Gandhi. It started on December 3, 1971, and the Pakistani troops surrendered on December 16.

“People were glued to their radios. Debdulal Bandyopadhyay was a newsreader at Akashvani. He had a booming voice, and listeners waited to hear him read the bulletins,” Mukhopadhyay said.

Like what happened in many cities in the western front over the past two days, blackouts after sunset were common in Calcutta in 1971.

The civil defence directorate of the Bengal government issued advisories to people on what to do to enforce the blackouts and how to respond to air-raid sirens. Both advisories were published in Anandabazar Patrika as the war waged on.

The advisory on blackouts published in the Anandabazar Patrika of December 8, 1971, requested residents to ensure that no light inside their homes was visible from outside; all lights for advertisements and those outside homes were to be switched off; two-thirds of headlights of motor vehicles were to be blackened and drivers were advised against overtaking.

In those times, Calcutta’s streets still had many bullock carts and horse-pulled carts. The advisory mentioned that lights inside bullock carts and carts were to be covered so that they were not stronger than the light of a candle.

Trenches had been dug in many places in the city.

Urban historian Debasis Bose, then a school-going child, remembers seeing trenches on the Rabindra Sarobar premises. “My uncle’s house was on Charu Avenue. We used to go to Rabindra Sarobar for walks in the morning. I had seen many small trenches. A family member told me that they were prepared as hideouts in case Calcutta was bombed,” Bose said.

The advisory on sirens — published in the Anandabazar Patrika of December 6, 1971 — said that the 9am practice siren would stop. The advisory asked residents to cover glass windows with thick paper and follow the instructions of the local wardens.

To the relief of many, the war was short-lived. Calcutta was not bombed.

In India After Gandhi, Guha writes that on the night of December 13, 1971, “Niazi received a message from Yahya Khan advising him to lay down arms, as ‘further resistance is not humanly possible’.”

General A.A.K. Niazi was commanding the Pakistan Army’s eastern command during the war. Yahya Khan was Pakistan’s president.

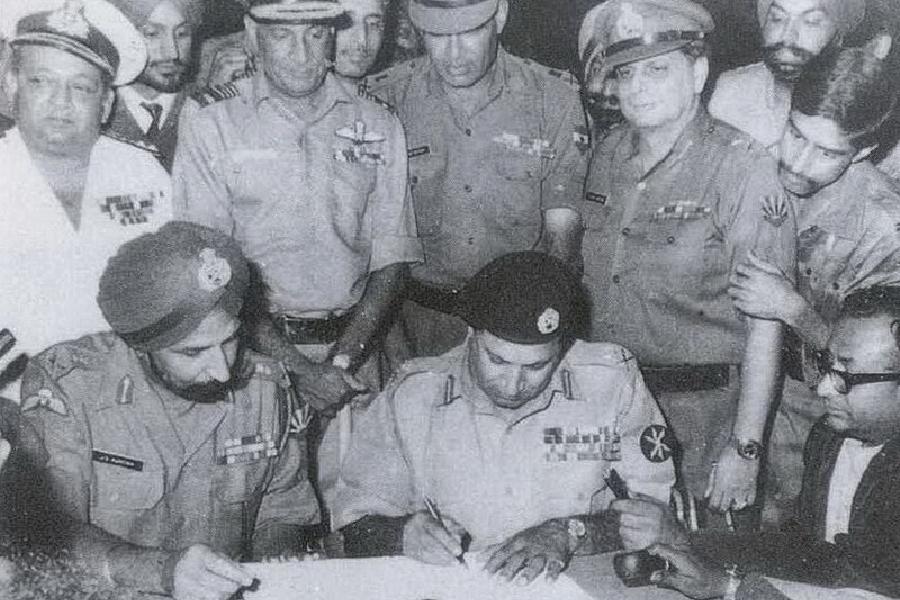

Guha writes: “On the morning of the 15th he met the American consul general, who agreed to convey a message to New Delhi. The next day, the 16th, Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora of the Indian Army’s Eastern Command flew into Dacca to accept a signed instrument of surrender.”