|

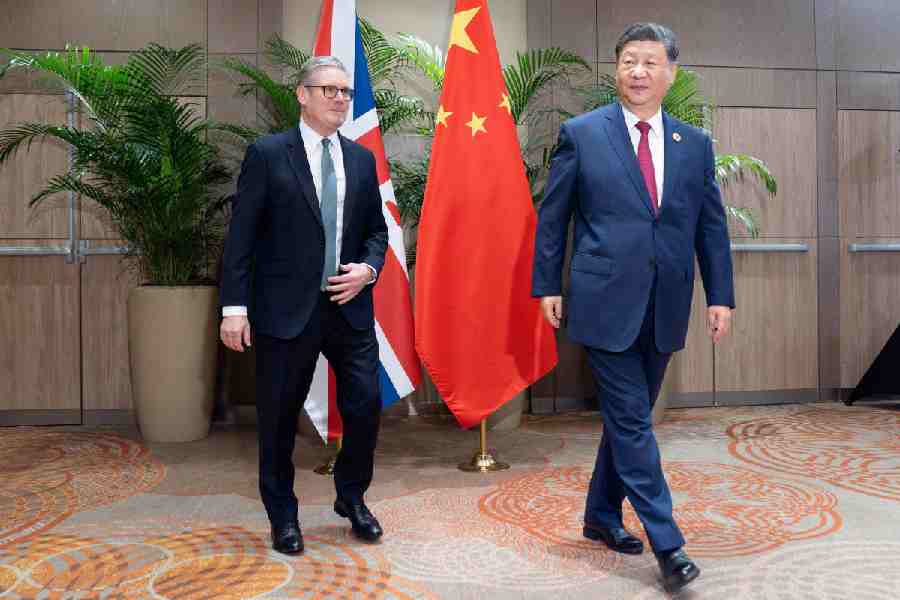

| Chandanashis Laha. Picture by Avijit Sarkar |

He detected a flaw in the Cobuild English Dictionary and convinced the publishers to make changes. His has earned the respect of world famous intellectuals for his knowledge of the language. He loves what most do not—grammar.

That is Chandanashis Laha in a nutshell.

The first student of NBU to post graduate with a first class first in English in 1981, Chandanashis Laha belongs to the rare breed of Indians who love to study the English grammar.

“The earlier edition of the dictionary had overstated the usage of the auxiliary ‘had’, which was misleading. I sent my arguments to Gill Francis, senior grammarian with Cobuild, who after much persuasion agreed to accept my suggestions,” says Laha.

The 1995 edition incorporated Laha’s points and acknowledged him for his contribution. He was made a prestigious offer by Cobuild—to join the team working on the Bank of English, a 200-million word corpus.

What made this literature student researching on William Golding stray into the field of grammar?

“I was doing my research work when I got an irresistible call from the land of English grammar. That was when I called it quits,” he says.

It was while teaching Growth and Structure of English Language, a philology textbook authored by Otto Jesperson and taught to students of English literature, at Raiganj College in 1986 that Laha stumbled upon a particular usage of the word ‘had’ which appeared wrong to him.

He wrote to Randolph Quirk of University College, London, vice-chancellor of University of London and the then president of British Academy, who had prefaced Jesperson’s book.

“The point you make is good and might well have suited Jesperson’s purpose. I would be grateful for your opinion,” are lines from the reply written by Quirk to Laha.

The letter also began a chapter of friendship between the two. Laha later flew to UK for his doctoral study in Applied Linguists under NBU.

What is that keeps this 40-something reader at NBU from tapping better opportunities outside the country?

The professor is quick with his reply. “Not all can become Nirad C. Chowdhury. I am not quite comfortable in foreign lands even in other parts of India. Siliguri is where my heart is. I simply cannot think of any other place,” he answers with a gentle laugh.

Perhaps the grammar man would agree with what Paul Kirseshner, a Conrad specialist, wrote to him in 1992: “The future of literature in English certainly does not lie in England and perhaps not in the US either, but in countries like your own, where words are regarded as having meaning and authors are read for what they have to contribute by virtue of their individuality to our collective knowledge and wisdom concerning life on this earth.”