|

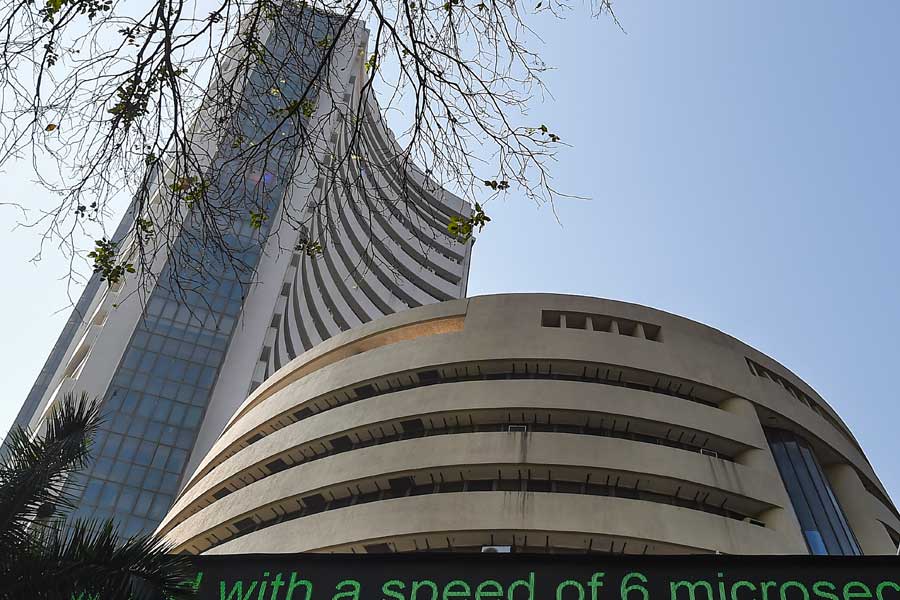

| MIXING MEMORY AND DESIRE: Is that all there is to write about the city? Picture by Soumitra Das |

I was conscious of the perfume in the air, of golden light, of cool, air-conditioned air, of people in T-shirts and jeans who were eyeing me strangely. I saw a lift going up and down that seemed made of pure golden glass. I saw shops with walls of glass, of huge photos of handsome European men and women hanging on each wall. If only the other drivers could see me now!

— Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger, published 2008

It was common knowledge that Job Charnock, the founder of Calcutta, smoked a hucca and held court under a neem tree somewhere in this vicinity. The area thus came to be known as Nimtalla (literally translated, under the neem tree). This happened more than 300 years ago.

— Sarnath Banerjee, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, published 2007

Aravind Adiga’s Booker-winning novel may just have given the argumentative Calcuttan a subject to debate. The motion before the house could be something like this: Indian fiction writers in English, when writing about Calcutta, are interested in the city’s past but not in its present.

Adiga writes evocatively about the New India, of Gurgaon and Bangalore. But when Sarnath Banerjee creates his graphic novel, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, just a year before Adiga, his narrator, though located in present-day Calcutta, explores its nooks and crannies largely as a time-traveller in the 18th and 19th centuries. Around the same time, Amruta Patil publishes her graphic novel, Kari, where she delves into lesbian angst in modern Mumbai.

In the world of Indian fiction in English, Calcutta is familiar turf. From Amitav Ghosh to Vikram Seth to Jhumpa Lahiri to Amit Chaudhuri, writers have visited the city by the Hooghly in their stories more than any other Indian metropolis.

At a recent book reading in South Africa, a reader pointed out to novelist Kunal Basu that a disproportionately large number of Indian authors writing in English are Bengalis who keep writing about Calcutta. Basu himself, in his fiction, has stopped by the city every now and then.

Old marks

The reader may have just stopped short of pointing out that a disproportionately large number of these “Bengali” writers do not live in Calcutta any longer.

And so, it transpires that the Great Calcutta Novel is yet to be written. Amit Chaudhuri, who has recently edited Memory’s Gold, an anthology of “writings on Calcutta”, has noticed that Calcutta hasn’t been the subject of a work in the same way that Mumbai has in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children or Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games.

|

| Amitav Ghosh |

|

| Jhumpa Lahiri |

|

| Aravind Adiga |

Of course, there can be no argument about the fact that a writer writes about what catches his fancy. Just as Adiga writes about the changing cityscape of India and the people lurking under its flashy exterior. The turn-of-the-millennium Calcutta too is getting sucked into a consumerist bubble like the one that Adiga’s hero, Balram Halwai, encounters in the streets and shopping malls of Gurgaon. (Incidentally, one of Adiga’s primary inspirations was the life of hand-pulled rickshaw-wallahs of Calcutta.) But the writers who have set their novels and stories in Calcutta have mostly preferred earlier decades or centuries in the city’s life — so much so that the choice of Vidyasagar Setu as a marker of the city (in Chitralekha Basu’s short story included in Memory’s Gold) appears odd.

Sarnath Banerjee’s Barn Owl takes the reader into the days of babu-culture in Calcutta. He gives his tale a subversive spin by digging up babu-Calcutta’s fringe characters like Gopal Urey and Rupchand Pokkhi — a device somewhat reminiscent of Nabarun Bhattacharya’s phyataru-novels in Bengali.

But the levitating, anti-capitalist creatures populating the seamy underbelly of Calcutta in Bhattacharya’s novels do not pop out from the pages of history, they are imagined products of the culture spawned by 30 years of communist rule. Among English authors, only Amit Chaudhuri, in his Freedom Song, has engaged with Calcutta’s comrade-culture of the late 20th century — with “Dipen Mandal breaking into Sing Cominternational on May Day to the accompaniment of his single-reed harmonium”.

But Chaudhuri agrees that Calcutta has a way of intimidating outsiders. Is that why Indian English novelists, most of whom could be described today as outsiders to the city, go back to their memories or fall back on research on Calcutta’s antiquity? When Amitav Ghosh writes about the Dhakuria Lakes and Gol Park in The Shadow Lines, it is the Calcutta of the author’s childhood and youth. Or the city becomes, as in Jhumpa Lahiri’s stories, part of the interior drama of middle-class families.

Malyaban Ghoshal, a sociology student, feels that even in the face of the consumerist onslaught, Calcutta holds on to its provincial character. This provincialism is hardly charming.

Amitav Ghosh divides his time between Calcutta, Goa and Brooklyn, but Ghoshal wonders what his life would have been like were he to be based in Calcutta: “He would write full-time, or teach along with it, hang out with academics from Jadavpur University and the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, spend days getting a small piece of research done at the National Library, and fight daily battles that the average Calcuttan now considers his lot. In short, he would be miserable, his creativity devastated, and there would be no The Hungry Tide, no Sea of Poppies.”

It is true, however, that “lost world” narratives garnished with a dollop of nostalgia suit Calcutta better than action-packed drama. In Anuradha Roy’s words, the city leaves a sediment on a writer’s imagination that other cities don’t. Her novel, An Atlas of Impossible Longing, she says, was intended to move about in fictional, non-metropolitan locations, but Calcutta stole into it and went on to occupy nearly half the book. Samit Basu has used the “sediment” to mould imaginary cities for his fantasy Gameworld series novels.

Inside outside

If Calcutta is the city of memories, then the nature of such memories is almost always unqualifiedly pleasant — too pleasant for the readers to imagine that a writer can pull out of it an Adiga-style, disenchanted, objective narrative. Except, maybe, someone like Neel Mukherjee. The Calcutta of his 2008 novel, Past Continuous, though located in the 1970s and 80s, is not one of idealistic student politics, art and poetry, but of domestic violence, squalor and broken dreams.

But even Mukherjee does not want to write about New Calcutta, not having lived in it for the last 16 years. “With any other city, this would not have mattered, but because this city was my home once upon a time, and because I knew no other city for the first 22 years of my life, I would put myself under so much pressure to understand the last 16 years that I feel I’d be too inhibited to write about it,” he says.

Amit Chaudhuri suspects that the question of authenticity scares writers. It is as if those who have moved away from the city have lost the right to comment on it. “But an insider’s view is not necessarily the correct one,” he says, claiming to have always written about Calcutta with “a sense of elsewhere”. Kunal Basu thinks, similarly, that a creative artist’s real test is to write about places other than his own. Rimi B. Chatterjee, who lives and writes in Calcutta, feels “the best writers are never at a disadvantage anywhere.”

The shopping mall

With or without the authentic touch, will the reader find the protagonist of a Calcutta novel wandering into a coffee-shop in a brightly-lit shopping mall to reflect on Hydra-headed life? Samit Basu says yes. Calcutta in its present-day glitz and gloom is the subject of his next novel, because he cannot help but feel attracted to “the incredible pace at which the city is changing”.

But this apart, will it be more of what Chatterjee calls “the endless emotional-baggage-carousal of the average NRI writer” who “seems to want to either punish Calcutta for being what it is or weep over it, or both”? Is there something in the changes taking place that might pull the novelist to today’s Calcutta?

Or it could be, as Chatterjee is convinced, that there is no New Calcutta, “We have rejected the new as if it were a virus falling foul of a hyperactive cultural immune system and sneezed our way back into the Seventies,” she sums up.

It is not surprising that all the above writers shudder at the thought of having to call the city ‘Kolkata’.