Dibakar Beij, nephew of Ramkinkar, the great modern Indian artist and sculptor, who gave fresh impetus to the art of scenography, wrote a moving account of how a nurse, who announced his uncle's death at SSKM hospital on March 23, 1980, and had no idea about his identity, first asked him where the dead man lived, followed by a query on his caste. When the young man told her that he was a barber by caste (Ramkinkar's original surname was Paramanik), the nurse declared insouciantly how they thought he was a Santhal. (There are many who still think so.) The next day the same woman was taken aback when a huge crowd gathered at the hospital to pay him their last respects.

It was easy to be misled by Ramkinkar's wild hair and dishevelled look, compounded by his fondness for the bottle. His unrefined appearance belied his love of books, including such formidable fare as Ulysses, and classical music, particularly Hindusthani.

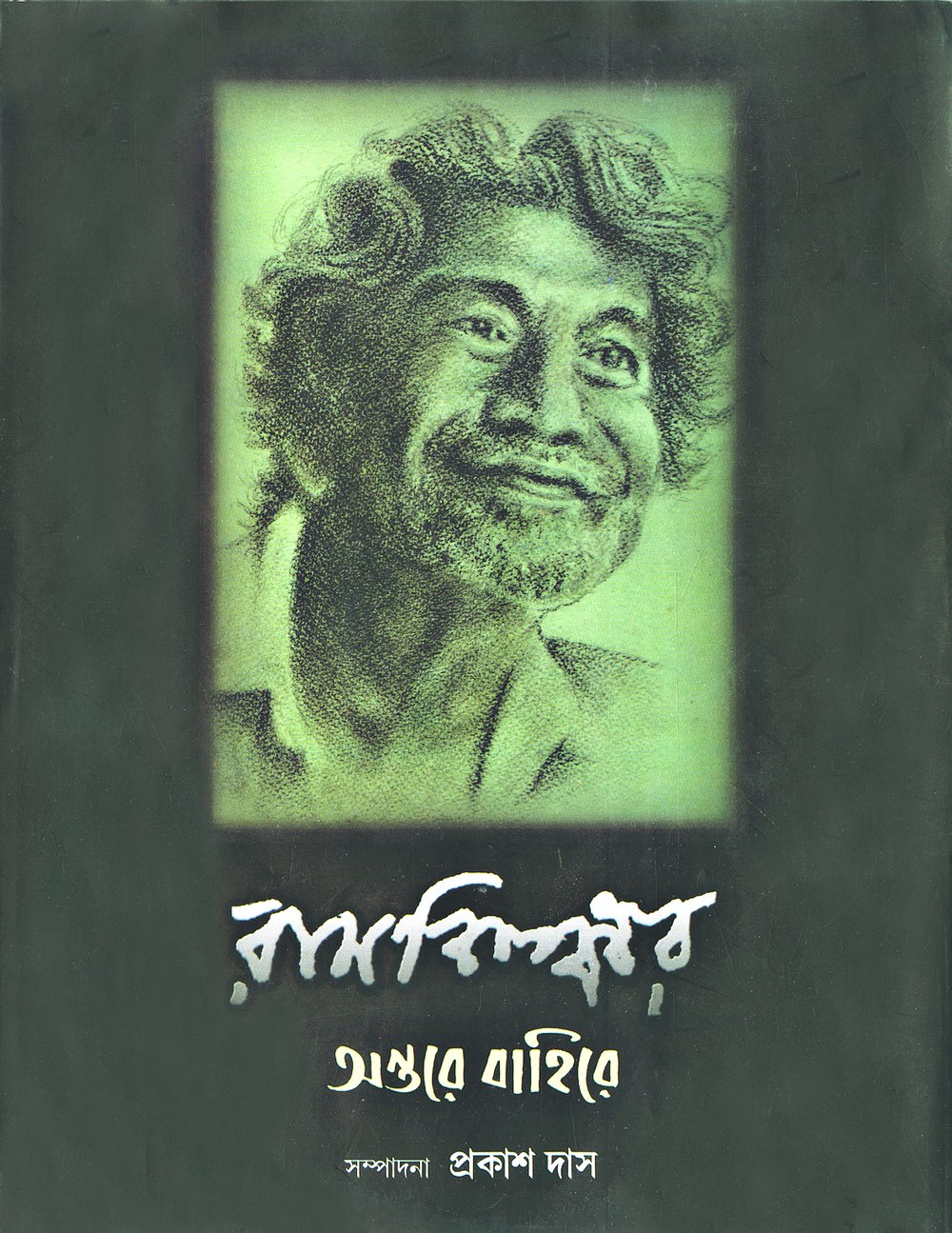

In his last years - he was 74 when he died - his prostate problem gave rise to a perpetual embarrassment - incontinence. These and other intimate details of his life are revealed in Ramkinkar: Antare Bahire, edited by Prakash Das and published by Deep Prakashan. It is a valuable compilation of writings, letters and interviews on this path-breaking artist and deals at length on various aspects of his genius. These are not only by the likes of Ramkinkar's friends and fellow ashramites, Benodebehari Mukherjee, Somenath Hore and Husain, disciple Shankha Choudhury, Sarbari Roy Choudhury, Dharmanarayan Dasgupta, Jaya Appasami, K.G. Subramanyan, R. Siva Kumar, and K.S. Radhakrishnan, but also by such humble beings as Bagal Roy, who helped him with his work - a tough job, for the artist worked tirelessly, come rain, come shine. There is also a long interview with Radharani, Ramkinkar's live-in partner and muse, taken after his death.

Prakash Das, who lives in Panagarh, has been interested in Ramkinkar from his college days when the artist became embroiled in a controversy over a bust he had made of Rabindranath with his eyes resembling two marbles gone awry. Then culture minister Jatin Chakraborty, who unveiled it in Budapest, was upset because it did not "resemble" the poet. Had Satyajit Ray and historian Niharranjan Ray not intervened it may have been removed.

Ramkinkar was an other-wordly being, but he seemed to have a talent for falling foul of the establishment.

In 1957, Ramkinkar was attacked by a professor of English at Visva-Bharati named Sudhindra Nath Ghosh during rehearsals of the play Antigone. The sapient professor could not stomach Ramkinkar's suggestions and tried to give him a drubbing. There is a detailed account of the furore this incident had caused then. Many such details enrich this volume. It would have been richer had the publisher taken enough care about proofing the text. The book has many art plates as well, although their quality is not satisfactory. But when a good book is selling for so little, one should not expect any more.