Kasturi Gupta Menon speaks about Kamala with a quiet maternal pride. She is conducting a tour of the landmark handloom and handicrafts store in the city that she has been looking after since 2010. The store is only one large L-shaped room at the ICCR building in Ho Chi Minh Street, but the tour takes long, because Menon stops at every shelf, every display, and describes every handpicked sari and object in detail, and every description ends in a story.

The Bengal taant saris alone come in at least three varieties: Phulia (for Tangail) and Shantipur in Nadia and Begampur in Hooghly. Some customers will drop in only for the Barmer curtains with their delicate applique work of white on white, which also hang in the store, illuminating the glass front.

The Kullu shawls, beautiful and affordable, are vanishing fast. A small, buttoned pouch, open at both ends, with Sanganeri print, works as a cable organiser. It is simple, beautiful and efficient: the perfect design.

Menon and her team have given the store their time, love and care. But now it is about to close down. On Saturday it starts its closing sale. The pandemic has taken its toll.

Kamala in Calcutta was started in 2008. A former IAS officer who had been development commissioner, handicrafts and handlooms, at the ministry of textiles at the Centre, and had retired as principal secretary of the planning commission, Menon took over Kamala’s charge in 2012 and brought to it the passion and experience of a lifetime spent among India’s arts, crafts and textiles.

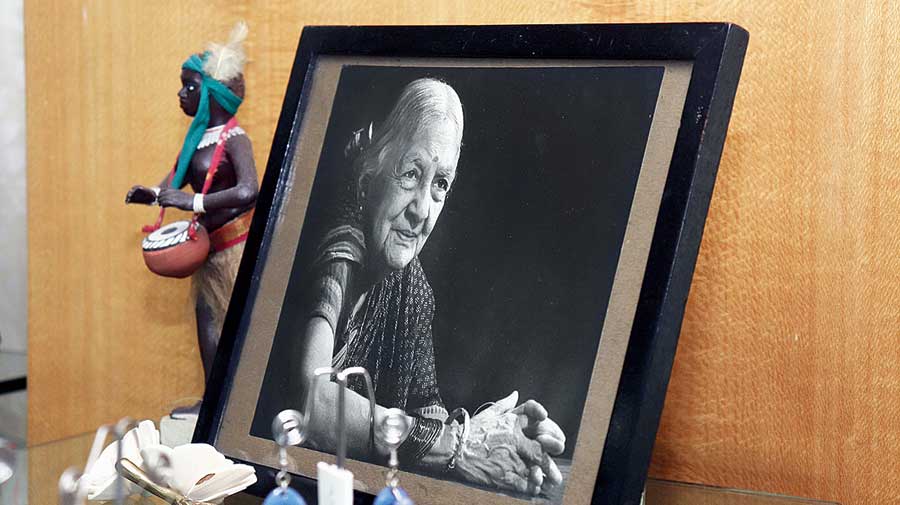

Kamala is the craft outlet of Crafts Council of India (CCI), a registered society started by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. Menon is its current honorary president as well. CCI is headquartered in Chennai and has decided principally that after the losses incurred during the lockdown, Kamala in Calcutta cannot be operational in the future.

Kullu shawls at the store Picture courtesy: Kamala

This is most unfortunate for many reasons, feel many. One, with the shutting down of Kamala, Calcutta will lose another beloved landmark. Kamala was like a little oasis in the middle of a dreary workday, not far away from a dreary work district. Handmade cloth and objects offer an odd comfort.

Two, and more important, the closing down comes at a time when it hurts most. The store sources its stock from weavers and craftsmen all over India. “We get our stock from artisans in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, as well as from the interiors of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and Odisha. And also from other craft-rich states in India such as Karnataka, Gujarat and Rajasthan,” says Menon. The lacquered toys from Chennapatna in Karnataka are a delight.

An ikkat sari Picture courtesy: Kamala

The Calcutta store has stocked the works of thousands of weavers and craftsmen, many of them National Award winners and members of co-operatives. The handloom and crafts sector have been among the worst-hit during the pandemic. To close a store like Kamala is going to be a second blow to them.

Chattopadhyay’s vision has guided the Kamala stores, which are located in Chennai and Delhi, other than in Calcutta. “She was deeply interested in the question of crafts as a livelihood,” says Menon. Chattopadhyay, who was instrumental in setting up Sangeet Natak Akademi and National School of Drama, was also the driving force behind the revival of arts and crafts in independent India, including the establishment of Central Cottage Industries. She was also a founding member of All India Women’s Conference.

“Under her influence, the craft sectors got a lot of money allocated to them in the 1st and 2nd Five Year Plans,” says Menon. They were also recognised as livelihood generating sectors and given equal weightage as agriculture.

Chattopadhyay saw the crafts as functional, Menon adds. They are a part of our everyday activities, our worship, and also integral to forms of culture such as theatre and dance, but ignored ordinarily by capital. “So it is more important that a store in her name should not close down now, when craftsmen need the most help,” says Menon.

Chattopadhyay had a special connection with the Bengal crafts. In the 1940s, after the famine, she was visiting Bankura, and staying with Menon’s family, when she spotted two old terracotta horses that belonged to one of the family attendants. She liked them so much that she got them as a gift from the attendant. These “Bankura horses” became an icon as the logo of Cottage Industries.

“Kamala should not be closed down,” stresses Ruby Palchoudhuri, who heads Crafts Council of West Bengal. It was Palchoudhuri’s idea to set up a Kamala store in Calcutta. She has always been a part of Kamala in Calcutta in a very supportive role in all its events. Kamala has hosted four events through the year, bringing much joy: Poila Baishak was for saris; Patram, held in July, was for household and lifestyle objects; the Puja event was for saris; and Christmas was about gifts of various kinds.

The store not only sourced traditional handicrafts, but has also innovated. “Tradition is not enough,” says Menon. Kamala experimen-ted with the colour mauve — “panaphool rong”, the colour of water hyacinths — and pink, and silver grey with the Shantipur weavers. Tradition evolves, says Menon. It is not a static thing. The same weave changes from village to village.

The craft is inseparable from its makers and is coloured by the environment, literally. Such interactions with the craftsmen go far beyond just the market. “We went into their homes, ate with them.” It was a vital connection.

Kamala may close down, but its last collection is still on display, if for a few days. Menon resumes her tour. A cluster of perfectly finished ladles are from Bankura, made of Akashmoni wood, and also from Burdwan. A set of exquisite weaves are from Bhagalpur. At one side, lies a bunch of Gondh paintings. Their colours are vibrant and their patterns delicate and fine. Why then the distinction between art and craft?

“This is art,” says Menon. “The artist, Ramkumar Tekam, had not sold a single piece when he brought them all over here,” she adds.