A well-meaning Dr Srivastava takes Piku aside in one of the final scenes of the eponymous Hindi film. He wants her to know that her late father, a man with chronic constipation, was absolutely convinced that her boyfriend too suffered from the same condition. Piku listens intently, strides up to Syed, confronts him with the truth and, after his stuttering confession, walks away from a future with a man possessed of a malfunctioning gut.

Comic effect notwithstanding, sluggish bowels are no funny business. Not in a man and never in a city. Unfunny too, if it happens to be your present or permanent address.

It is a former corporation man who proffers the bowel analogy as I try to understand Calcutta’s chronic waterlogging problem, something made worse every single monsoon.

“This is exactly as it would be if someone had trouble moving bowels,” says Nilangshu Bhusan Basu. The former principal chief engineer of Kolkata Municipal Corporation or KMC is answering a specific question about the point of a Rs 500-plus crore project undertaken in 2007 to rehabilitate critical stretches of the city’s combined sewerage and drainage or S&D system. As I paddle through discussions and research papers about sewers and catchpits, soffits and inverts, bricks and GRP liners, I clutch at the bowel imagery for dear clarity.

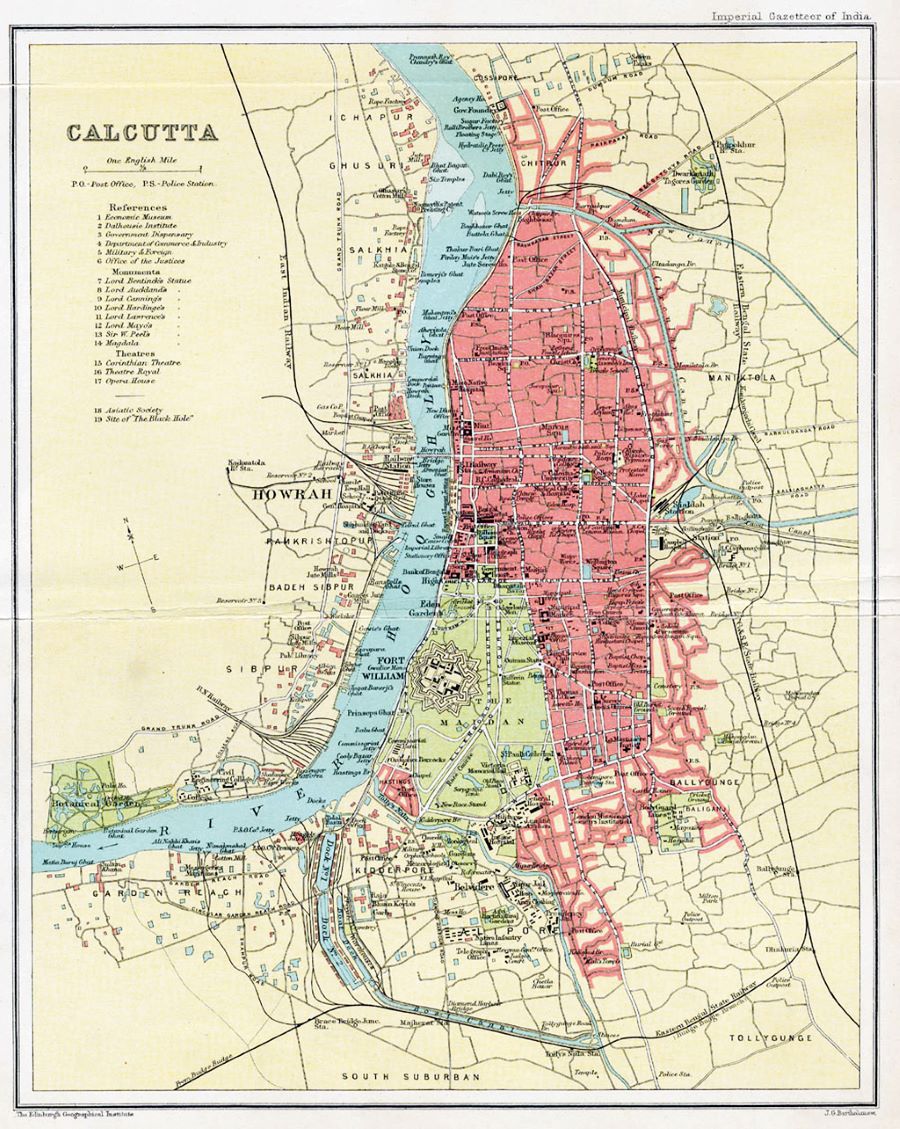

A 1908 map of Calcutta showing the broad area serviced by the sewerage and drainage system Courtesy Institution of Civil Engineers Publishing, UK . From the Imperial Gazetteer of India, New Edition/ University of Chicago Library, USA

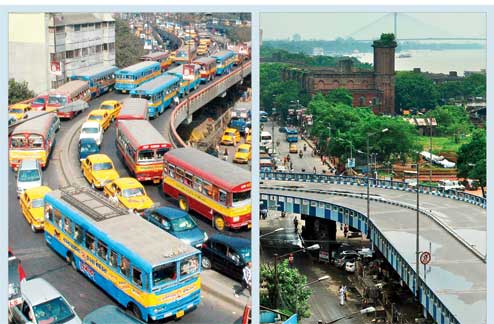

July 30, 1982. Headline of a front-page story in The Telegraph, right next to the one that says “Amitabh Bachchan critical”: “Downpour upsets Calcutta life”. The copy reads, “The downpour, which began at 5.30pm, continued till 8.30pm. The city’s main arteries were choked as water reached knee level...” Fast-forward five years. Same date. Headline reads: “Downpour paralyses life in city”. Excerpt from copy: “...many city roads were flooded within an hour... unprecedented waterlogging.” Headline from July 1986: “100-year-old sewer collapses”. July 1990 headline: “Downpour paralyses south Calcutta”. June 12, 2020 copy: “The monsoon’s first rain led to waterlogging along the kerbs on several roads...”

Year upon year, the same story — 131mm of rainfall in the past 24 hours; 220mm rainfall in the last 17 hours; 119mm rainfall between 8.30 and 11.30am; traffic haywire; schools closed; no trams; trains delayed; man electrocuted; child (falls) down manhole.

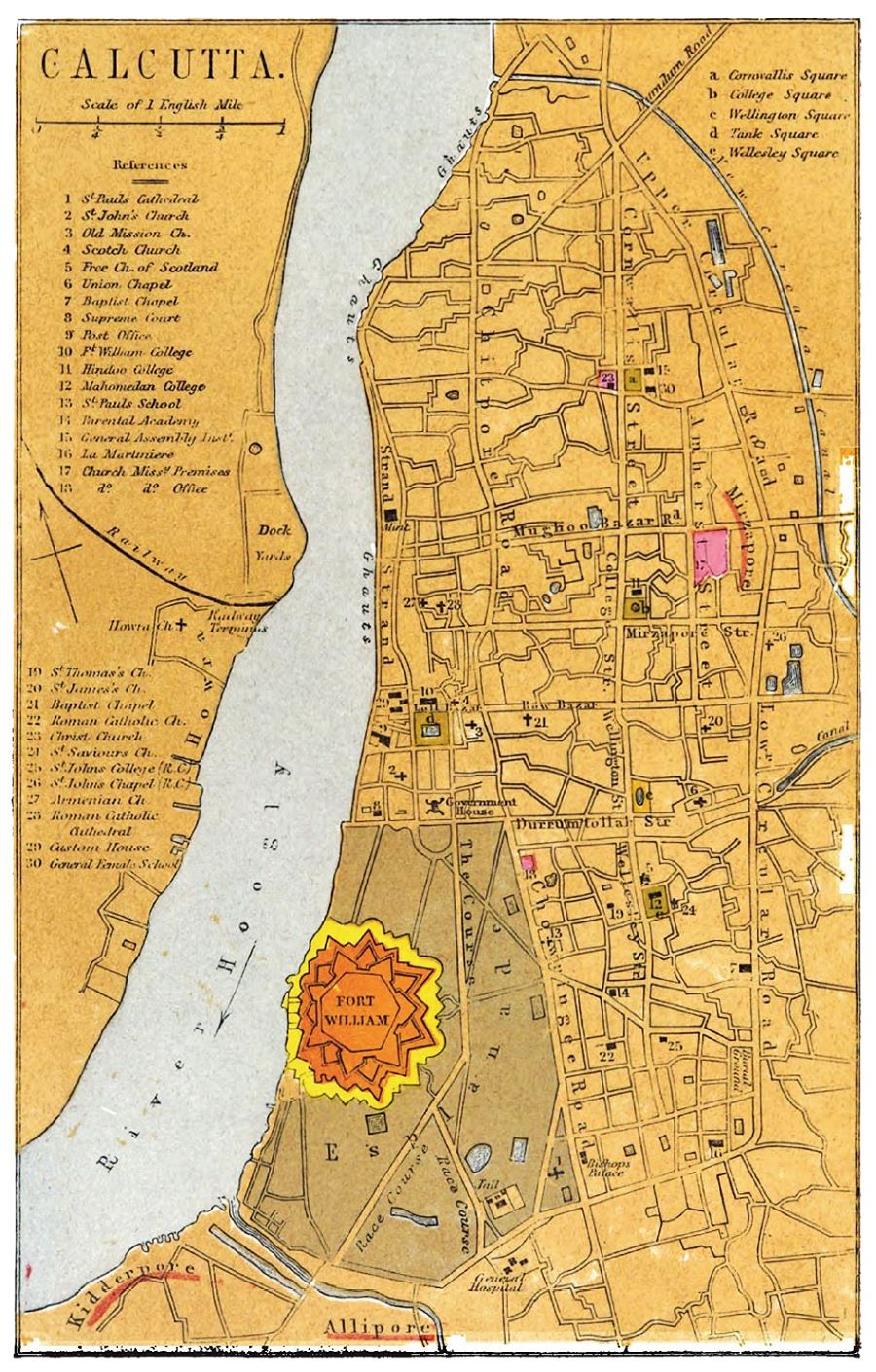

An 1862 map of Calcutta showing the broad area serviced by the sewerage and drainage system Courtesy, Institution of Civil Engineers Publishing, UK. Made available by CMS, the Church Missionary Atlas, 3rd edn. Shelley, Jackson and Halliday, London, UK

And yet, those in the know say we have the very first centralised scheme in all of Asia. “Even before Joseph Bazalgette submitted his plans for the central sewerage scheme of London to the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1856, in December 1855 the municipal commissioners of Calcutta had recommended William Clark’s scheme for the Calcutta Town System for approval to the government of Bengal,” says Ayanangshu Dey, who is an independent water and wastewater engineering professional. Civil engineers go into rhapsodies about the size of the egg-shaped sewers Clark built — anything between 6ftx8ft and 10ftx15ft — after factoring in the intensity and spread of the Indian monsoons. They point out that here is how “our” sewers are different from the ones in London, a city that receives evenly distributed rain through the year.

So, how did we get here?

There was a major congenital defect. In 1690, Job Charnock proclaimed that anyone could settle down in Calcutta. Jump ahead a 100 years. Says Sarmistha De, who has co-authored the book Calcutta In The Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration, “The new city quickly developed into an outpost of the booming world of commercial and industrial Europe. It was a port city of great strategic importance, but it also had an unhealthy marshy topography and an atmosphere that took a heavy toll on human lives.”

In an 1869 report, the then sanitary commissioner of Bengal, David B. Smith, observes: “It is worthy of note that a sewer empties itself close to each of the principal bathing ghats... Some of the sewers have acquired great notoriety, and it has long been known that the ships moored near them have sent more cases of cholera to the hospitals than others moored elsewhere.”

Had it not been for Lord Wellesley, Calcutta’s bowels would have never budged.

In 1803, Wellesley, who was then the governor-general of Bengal, said in his Minute on the improvement of Calcutta: “An original error has been committed in draining the town towards the river Hooghly. And it is believed that the level of the country inclines towards the Salt Water Lake and consequently that the principal channels of the public drains and water courses ought to be conducted in that direction.” Thus he set in motion a series of initiatives and counter-initiatives that culminated in a corrective called the Clark’s Scheme half a century later.

“Clarksaheb proposed a scheme that would use the natural gradient to drain Calcutta towards Salt Lake,” says Dey. He hammers home the point that using natural gradient of a geography while designing any S&D system might be common knowledge now, but in the 19th century it was sheer genius.

Clark’s scheme constituted five large sewers, one huge super sewer (town outfall) and a pumping station. It covered 19 square kilometres of the core city and is a combined system, meaning, it carried spent water (water from the toilet, bath and kitchen) as well as storm water run-off. It handled a sewage load of 1.27 cubic metre per second. At the time, the population of the city was two lakh. By 1867, Rs 4.5 million had been spent. Today, the area under KMC is 200 sqkm. Besides the regular increase in population, there was a population explosion with the influx of refugees at the time of Independence in 1947 and upon the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. Says Basu, “The resident population of the core city, according to the 2011 census, is 4.57 million. The visiting population is more than seven million.”

As planned by Clark, all of the sewage would go to Palmer’s Bridge Pumping Station in the eastern extremity of the city and, thereafter, into the Bidyadhari river. Later, when the Bidyadhari dried up, chief engineer B.N. Dey devised a scheme to lift sewage to a high-level, thereafter draining it all into Tangra Creek. The main sewers of Clark’s scheme comprised 61km of brick sewer and 60km of stoneware pipe sewers. Today, according to KMC, there are 200km of brick sewer and 1,784km of piped sewer beneath our feet.

“Do you know that over 95 per cent of what flows through the S&D system is rainwater (storm run-off in technical parlance), only a small fraction is sewage,” Dey asks. I know now, and I want to know why despite this Calcutta gets so constipated every monsoon?

Also, this year, post Amphan, will the waterlogging be worse? KMC’s director-general S&D, Amit Kumar Roy, says routine desilting (cleaning) of sewers was impeded for a while because of Covid-19 but has picked up now. I ask him if KMC is the one to blame for any waterlogging and he replies, “Three things determine waterlogging — how much rainfall, over how much area and what intensity. But these are uncontrollables. To work on what is controllable — cleaning sewer lines, alerting people about littering, conservancy service related to garbage — is our duty. If it has not rained too much yet there is localised waterlogging, then tell us.”

As I come to understand, there is no one one answer to the waterlogging conundrum.

There are legacy defects. Dey says, “Clark used brick and mortar instead of the more durable Portland cement used for the London sewers. The scheme also ignored a critical suggestion while planning sewer transition which, simply put, leads to waterlogging.”

Then there are anthropogenic realities. Dhrubajyoti Sen, a professor in the civil engineering department at IIT Kharagpur, talks about urban flooding, which is a function of changes in land use pattern, reckless real estate resulting in more paved city area, less soil surface to allow the water to seep in. Experts point out exasperatedly how every time a new locality develops, work on the S&D system happens last.

There are poor civic habits too. People throw garbage on the road, which goes on to clog the catchpits actually meant to screen and receive stormwater and then direct them into the sewers.

Then there are the mysteries. Once, the sewers were connected to the Hooghly with lock gates, at high tide, twice a day, the river waters “flushed” the sewers, keeping them clean. But that feature has been deactivated. And the not-so-mysterious factors. The North-South Metro rail construction intercepted major sewers, and created “anomalous inverts” and “hydraulic bottlenecks”.

And then there are systemic issues. S&D is the KMC’s job, but the canals through which the water must pass come under the irrigation department. Something like having the neighbour in charge of your alimentary tract!

A one-of-a-kind hi-tech sewerage rehabilitation work was carried out under Basu’s supervision between 2007 and 2014. It braved all kinds of challenges from little things like sewer rats to big things like safety issues to sensitive things like public convenience to onerous things like jangles of wires and cables underground. But even great initiatives need sustained follow-ups.

Some people will cite lack of funds. But as one expert who did not wish to be named said, “Look at Mumbai and its chronic waterlogging problem. Yet BMC has an annual budget in excess of Rs 30,000 crore. KMC’s budget is Rs 3,000 crore. Where there is waterlogging, money is not the issue, mindset is.”

Translation — same old shit.