|

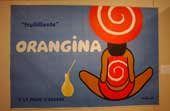

| In Villemot’s poster, the bottle of the drink is made of orange peel |

If a picture speaks a thousand words, a poster packs a lot of punch into them. Selling either a commodity, an idea or an event, a single poster can be as compelling as an ad blitz, the most eloquent of the kind effectively breaking down barriers of language, age and culture. The exhibition on 50 years of French poster art, covering two floors of the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, demonstrates the power of this medium, and how, even half a century later, their message is still as loud and clear as the day they were produced. For, they combine creativity of the highest order with a very strong sense of graphic design.

The posters for Bally over the decades are a case in point. Bernard Villemot began in 1973 with two women in nothing but their black and red mops and shoes in the contrasting shades of blue and yellow. This could have been Matisse, but the appeal is more direct, as the well-shod feet stand out against the stark black background. By 1979, the poster artist has introduced a pair of male legs and feet against a pair of high heels. And by 1989, the shadow of the high heels has turned into the silhouette of a man’s shoe. All three images are smart, clever and sexy, and despite the very restricted palette and lines, nothing is left unsaid, though the only copy used is the brand name.

Another poster designed for the same brand by Jacques Auriac shows the feet of a man and a woman in evening dress and by suggestion, allows the viewer to enter a world of romance and enchantment. There are hundreds of such telling posters in this brilliant exhibition, organised by Les Amis de la France along with Alliance Francaise de Calcutta and the Embassy of France in India. It records the evolution of poster art in France where colour, line, typography and wit are the various tools that the artist is free to wield. For example, for a Citroen campagin, three hybrid creatures were created — a fish with bird’s feet, a half-bird, half-swan, and a mer-angel — to stress “the elasticity of air and the flexibility of water”.

The beautifully-produced and profusely-illustrated catalogue traces the development of the modern poster in France born in the 19th Century. “Generation after generation — we are now in the sixth generation — this tradition was perpetuated. The poster offers the advantage of a possible double-reading: it is both a work of art and a sociological document,” writes Alain Weill in the introduction.

Raymond Savignac, to whom the exhibition is dedicated, epitomises the poster artist with his talent for articulating his ideas through simple but extremely effective concepts, more often than not infused with wit. His poster for the soap Monsavon shows a bar of the product emerging from the udders of a cow to stress its milky consistency. His visual gags set the trend for poster art of that period.

In another poster, the Notre-Dame cathedral literally raises its hands to protest the construction of a highway on the banks of the Seine. Alain Le Quernec’s image of St Sebastian pierced through with cigarettes, instead of arrows, speaks volumes for a campaign to raise awareness about respiratory diseases. The latter was born decades after Savignac but the ability to get across a message by using simple visual devices is the same.