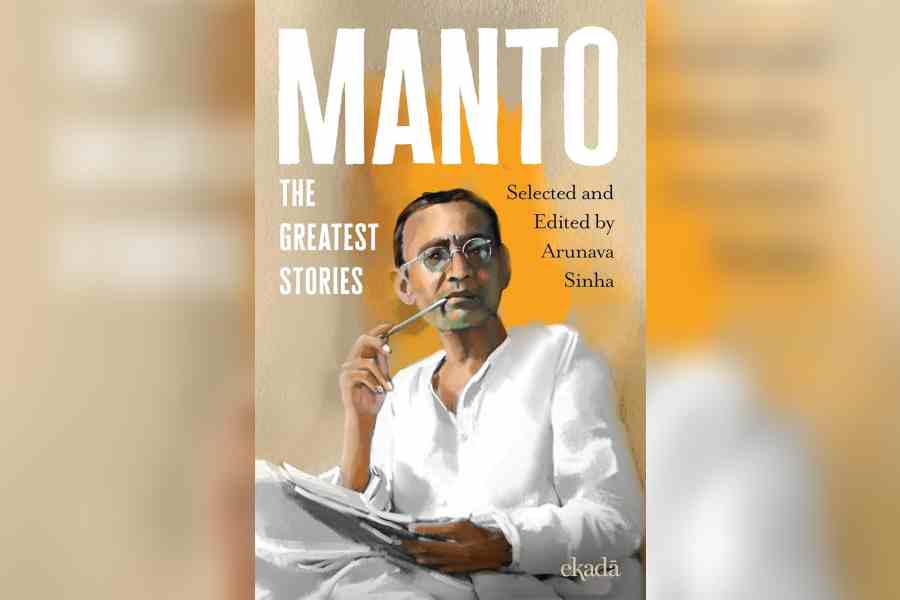

Sadat Hasan Manto’s stories, originally written in Urdu, have been translated into many mainstream languages. The short story writer, playwright and essayist whose sharp pen laid bare the hypocrisies of the society with its unapologetic ink, and refused to toe the line, connects with every generation. The latest translated work, Manto The Greatest Stories (Ekada, an imprint of Westland Books), in English, brings the focus back on 17 stories of the feisty writer, by eight young translators who are university students. Under the guidance of Arunava Sinha, who has a robust oeuvre of translated works, the budding translators have translated works like Khol Do, Kaali Shalwar, Buh, Dus Rupay and others.

Talking about the idea behind the book, Sinha, professor of the Creative Writing department at Ashoka University, said, “The idea was to see how a new generation looks at Manto. Manto has been read over the years by every generation, and I think each generation has found a new relationship with his work. I have never taught Manto to my students at the university and haven’t used Manto directly in any of my texts. Manto’s writings always come up in the course of conversations because it is a sort of surrogate for Partition literature, and so I was very keen to find out how the new generation looks at Manto, since they have no direct memories of the Partition. Very often, they don’t even have inherited memories because they are two generations away, if not three. So translation is the best way to read a text very closely, as you can read but you will only take what you want from it.”

Arunava Sinha

Manto’s stories have a profound effect on the readers, and what started as a means to know how the young guns perceive stories that are not popular fiction but a courageous mirror to society, also helped Sinha gain from it. “I have learned a great deal from young people over the past six or seven years that I’ve been teaching at the university. It’s a fresh way of looking at the world, at history, at justice, at right and wrong… and I see these perspectives very strongly reflected in their reading of the classics. This generation, having read a great deal more, having been exposed to a great deal more by way of films, media, are able to bring their own perspective into these classic texts.” Continuing on the relevance of classic stories, he added: “The whole exercise re-emphasised what makes a classic a classic. The core values stay unchanged for every generation of reader. So it was also a sort of validation of that fact that even a new generation that has grown up with a very different set of views of the world continues to derive the same core values from a text, like Manto’s, that my generation did or even the earlier generation did.”

Arjun Bhandari, Arya Shukla, Ayaan Shariq, Keya Sengupta, Shubham Gupta, Sonakshi Gupta, Sonal Dugar and Stuti Sharma are the fresh talents who bring alive Manto’s stories with their flair. For most of them, this is their first piece of published translated work. “This time they did it entirely on their own, and it wasn’t a classroom situation where there was constant silence or anything. They were on their own pretty much,” informs Sinha, pointing out that they referred to both Hindi and Urdu versions of Manto.

Sinha also kept the selection process of the stories quite organic and democratic. “I left the selection of the stories to the students because I wanted them to pick a story that talked to them and not impose a selection on them.” Talking about his approach in keeping the essence and flavour of the story intact, he said: “I didn’t edit these stories with constant reference to the original. I took them as texts that people would be reading in English and therefore looking at them from that point of view, because I believe that you have to trust the translator to understand the story well enough to ensure that nothing is distorted. Things change between one language and another, and that cannot be denied but the point is, are you doing the best you can in the new language? I am familiar with the stories, so I didn’t have to constantly refer to the original line by line. I read them all in translation in the past, in the Devanagari script. So, it was as much to do with my own memory of these stories as it was to do with the text that was in front of me.”

Sinha, who translates Bengali fiction and non-fiction into English, and English fiction, non-fiction and poetry into Bengali, also talked about the renewed interest in translated works in reference to Kannada author Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp’s big win at the Bookers. Being candid, he made us note: “Honestly speaking, translated books are selling far fewer copies now than ever. What is growing is a larger number of excellent translations; more publishers are publishing translations. However, when it comes to the reader’s interest, it is concentrated. When one book wins the International Booker, like Heart Lamp did, there is a huge wave of interest, and that book goes on to sell 100,000 copies. But your average translated book in India is fortunate if it can sell 2,000 copies. So, you can see the vast gulf between people who genuinely read translated literature, which is their own literature, and literature in some other parts of the world. Everywhere else in the world, they read their own literature more, but in our country, we seem to read imported literature more. And our own literature is far less. So I don’t know what will change that. But it is still fantastic that so many good translations are being published. And very importantly, that so many young people are translating books.”

Sinha has an exciting lineup of upcoming releases and he is more ecstatic for The Bengal Reader. “It is a collection of fiction in the form of stories, excerpts from novels, non-fiction in the form of essays, letters, recipes, poetry, and some plays. All of this is going to come together, covering 200 years of writing, Bengali writing, through the 19th and the 20th centuries, coming right down to the 21st century. This is going to be published later this year in a mammoth volume by Aleph.” His other projects include an English translation of Sakyajit Bhattacharya’s Sheshmito Paki; The Madhopur House, his first Hindi translation; and a slim volume of Amuchu by Krishnapriya Bhattacharya.