On 2 October 1950, Charles Schulz and his friend Jim Sassaoill walked half a mile uptown in Minneapolis to a large newsstand that sold out-of-town newspapers. They were there to pick up the papers carrying the first appearance of Peanuts. Even after 75 years, the impact of the comic strip on the history of cartooning remains immeasurable. Still appearing in reruns 25 years after the death of its creator, the enlarged head and curly forelock of Charlie Brown continue to show up in publications as well as on television, thanks to a creative partnership with Apple TV+ — the home of Snoopy and friends.

The secret to the longevity of Peanuts, perhaps, lies in its element of precocity — how else do you explain Linus’s understanding of the writings of Dostoyevsky and Orwell — and in its chronicling of defeat as a springboard to success.

“If Peanuts chronicles defeat, it is probably because defeat is a lot funnier than victory. Most of us know what it is like to lose some kind of contest, and we can identify with the loser,” Schulz said in an interview with Penthouse in 1971.

Unwinding with a collection of Peanuts strips is as much a pleasure for a 50-year-old as it is for a 10-year-old because Charlie Brown has all the worries that worry us. He voices the insecurities we feel. Children often believe they don’t fit in, like Charlie Brown. Adults always harbour self-doubt, like Charlie Brown.

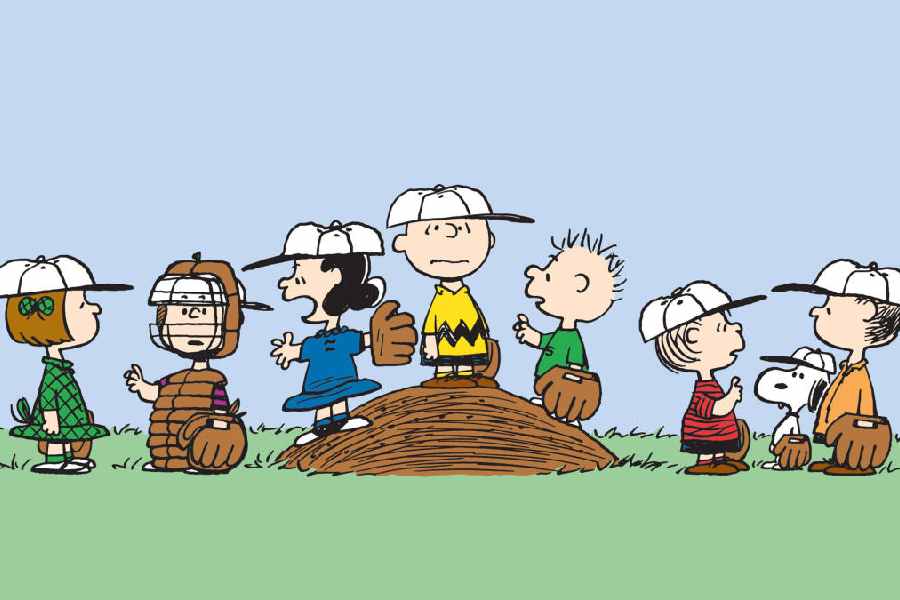

Over many decades, the comic strip captured the uncertainties of its times, many of which remain unchanged. Yet there is also an element of certainty that the strip celebrates — Charlie Brown will always feed Snoopy, Snoopy will always lie on top of his doghouse and Lucy will often get kissed by Snoopy.

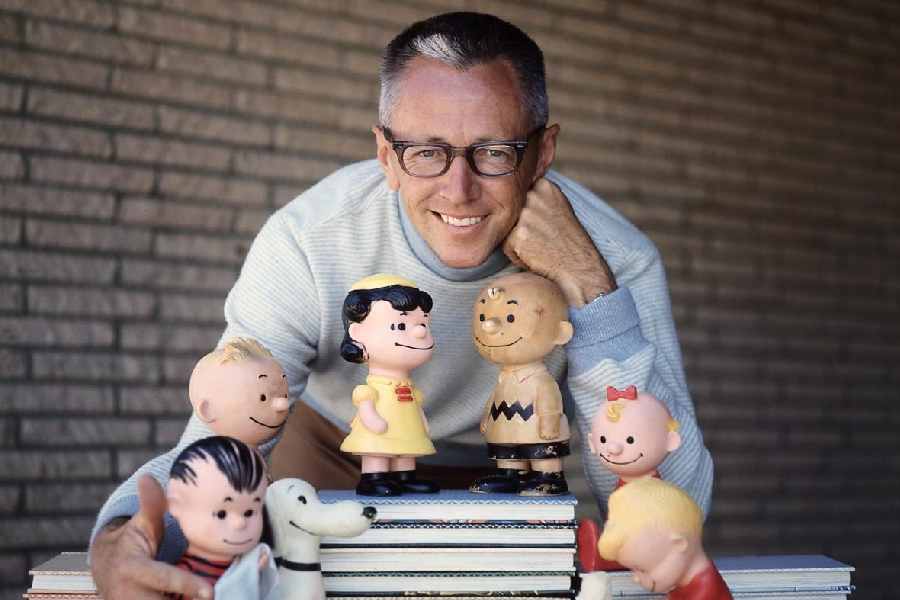

Charles M. Schulz was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on November 26, 1922. Getty Images

The doubts that flow through the pages of Peanuts also run through people across geographies. As Sparky (nicknamed after the horse Spark Plug in the comic strip Barney Google) — aka Charles Schulz — said: “I feel that Peanuts reflects certain attitudes of life in our country today and perhaps some basic fears. However, I like to think that these things are part of the entire human condition and not simply something involving one generation of people in one country.”

If the Peanuts kids were old enough, they probably would give some serious thought to running as candidates in the next US election. Although these kids are politically-minded, they are not partisan. They do not favour Republicans or Democrats, Conservatives or Liberals. Their only criticism is of people who are too busy to keep up with present political life or too busy to make their own commitment.

If the kids could have their way, they would commit themselves to all sorts of causes. They would probably join freedom marches and attend political rallies. Politics is not a business in which you can afford to be second best. They don’t give the feeling that one should get elected to satisfy one’s ego, one’s thirst for power, or unquenchable greed.

Unknowingly, perhaps, Schulz set out to create a strip that is always quotable. Beyond that, the drawings remain pleasant to look at, and the characters themselves feel quite real.

Schulz drew from experience. “I’m interested in doing a strip that says something and makes some comment on the important things of life. I am probably a little bit of Charlie Brown and a little of Lucy and Linus and all the characters. It would be impossible in this kind of strip to create any character and not be part of it yourself,” he told Penthouse.

That’s ‘all right’

Schulz never wanted his characters to be like normal children. Through them, he made references to Dostoyevsky and Beethoven accessible at an early age. The strip’s concerns were familiar: friendships, pets, schoolyard crushes and whatnot.

Drawing a comic strip was his “life-long ambition”, born of his fascination with the “funnies”. As a child, he read strips such as Popeye, Buck Rogers, Mickey Mouse, Terry and the Pirates, Captain Easy, Li’l Abner, Prince Valiant, Krazy Kat and S’matter Pop.

He drew his way through grade school and high school but was disappointed when his cartoons for his high school annual were not printed.

After the Second World War, he lived in St Paul with his father, who was a barber. No wonder the unseen barber in Peanuts is much loved.

Schulz got a job with a correspondence school in Minneapolis called Art Instruction Schools, where he worked for five years. There, he developed his drawing and creative ability. One day, he mailed his work to the Saturday Evening Post. It was a one-column cartoon, for which they paid $40.

It was during this period that he began drawing cartoons involving little kids, and the St Paul newspaper agreed to publish them “on a once-a-week basis”. This went on for two years.

Snoopy Museum Tokyo. Peanuts Worldwide LLC

Then he began selling more cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post. “Finally, I decided I ought to try to improve my standing with the St Paul paper. I asked the editor if he wouldn’t run them on a daily basis, rather than just on Sunday, and he said ‘No’, he didn’t have room for a daily feature and besides, he had a lot of syndicated material. They were paying me $10 a week at the time, which was normally what they might pay for a top-quality syndicated feature. I was always appreciative of his just giving me the start, so there was no bitterness.

“I asked him if he could run it along with the Sunday comics, but he said this was absolutely out of the question. So I said: ‘Maybe you could give me a little more money for doing the feature?’ He said ‘No’, the budget wouldn’t allow it. Having a little more confidence, having sold those cartoons to the Post, I said: ‘Well, perhaps I should just quit drawing it,’ and he said ‘all right’. I’ll never forget that. He just said, ‘all right’, and that was the end of my two-year career with the St Paul Pioneer Press.”

Sniffy becomes Snoopy

Next came a series of rejections, but there was no giving up. In the spring of 1950, he took the best cartoons he had done for the Pioneer Press, redrew them and submitted them to United Feature Syndicate.

The reaction was positive enough for him to be invited to New York for further discussions. “I took along six daily comic strips which had a new approach to humour in strips. If you were to see them now, they wouldn’t look like much, but at the time, it was new. There was a very light touch to them, and in a way, they were subtle, and it was a unique approach. They decided they would rather have a strip than the panel cartoons. So when we signed the contract, it was with the agreement that I was to create definite characters and draw a daily comic strip,” said Schulz.

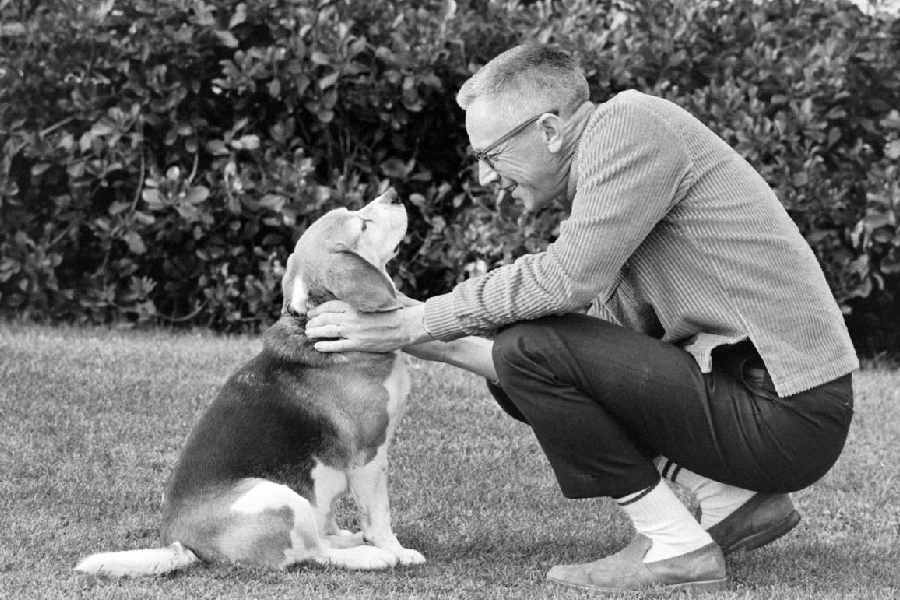

Charles M. Schulz with one of his family’s five dogs in California in 1967. Getty Images

He added some of the “kid characters” he had been drawing, naming one Charlie Brown and one Patty. “I’d always been drawing little dogs in the strip, so I named one Snoopy, the one I would be using the most. Actually, he was named Sniffy at first. But I was walking past a newsstand one day and saw a stack of comic magazines and one was called Sniffy, and it was about a little dog. So I had to go back and change the name to Snoopy. The real dog who was the forerunner of Snoopy was named Spike. He was bigger than the beagle that Snoopy has turned out to be, but he was kind of a wild dog marked in a way similar to Snoopy. I had another boy character named Shermy, who was named after a friend of mine. Those were the four characters in the strip the first week. Later on, I added Violet, who was supposed to be the pretty girl in the strip, and then Lucy came along and her brother Linus.”

‘Snoopy is sort of universal’

Soon, we found Charlie Brown at Lucy’s psychiatric help stand, saying, “I have deep feelings of depression.” The response is swift: “Snap out of it! Five cents, please.” No doubt, everyone loved the humour.

“The first thing we always describe is the humanity of the characters. Each character represents a human personality with all of its complexity, but also with its endearing quality, so it’s very human. Sparky would say, ‘Don’t forget the art.’ Every panel has to be beautifully drawn and executed. I think humanity is in the strip, in the stories of the strips, in the way that characters interact with each other, and it’s very true to life. It’s true that people see their own childhoods and their own lives in the strip,” Jean Schulz, the legendary cartoonist’s wife, told The Telegraph a few years ago.

Keeping the fire of Sparky’s creativity alive are the animated series that Apple TV+ continues to deliver, along with the brilliant wallpapers when using the Apple TV device. The shows remain faithful to the craft of the creator. Viewers can identify with every story in the series — be it Snoopy meeting Charlie Brown, kites getting stuck in trees, or Lucy’s psychiatric booth in operation.

When The Snoopy Show debuted in 2021 on Apple TV+, it was a breath of fresh air at a time when children’s TV remained largely predetermined, cramped with superheroes and flying cars. The Apple TV+ show questions the meaning of life itself, just as Charlie Brown and his pals did in the comic strip that ran in more than 2,600 newspapers, reaching countless readers in 75 countries.

Charlie Brown in Snoopy Presents: A Summer Musical, available on Apple TV+. Apple

Jean told us that the “cleverness of translators” who worked on Peanuts was key. She said: “Sparky used to wonder how they translated some of the comic strip, because some things don’t translate. For example, baseball. There are 3,000 baseball strips, but baseball doesn’t translate in every culture. I mean, they play football a lot more. I think part of (the popularity lies) in the translation. It depends on how it was translated and the cleverness of the translator. And then he would say, the art. It was pleasant to look at. Snoopy is sort of universal, people can enjoy Snoopy without any context, because he does funny things — he jumps and dances and pretends he’s a vulture and then pretends he’s something else. Snoopy has his own life. I think that Snoopy has often been the (entry point) of the comic into other cultures.”

Peanuts is bereft of dragons and witches. It revels in catchphrases like “Good grief!”, “Augh!” and “Rats!”. There is disappointment across the strip: Lucy is crabby, Linus never sees the Great Pumpkin rise on Halloween, and Charlie Brown’s love for the red-haired Francesca remains unrealised.

Despite this, the comic strip celebrates perseverance, teaching us to take our passions seriously, like Snoopy trying to write and Charlie Brown trying to win at baseball.

Snoopy is actually “an image of what people like a dog to be,” Schulz once said. “But he has origins in Spike, my dog that I had when I was a kid. White with black spots. He was the wildest and smartest dog I’ve ever encountered. Smart? Why, he had a vocabulary of at least 50 words. I mean it. I’d tell him to go down to the basement and bring up a potato, and he’d do it. I used to chip tennis balls at him and he’d catch and retrieve ’em.”

After 75 years, you may wonder what Schulz thought of cats. A cat named Faron appeared briefly in 1961. Jean Schulz has the last word on the matter: “I don’t think he had anything against cats, and he had a cat in the comic strip for a little while. The cat’s name was Faron. There was a musical star named Faron Young. But I don’t know if the cat was named after Faron. It’s a little before my time, but he said when you put a cat in the strip, it turned Snoopy into a regular dog, and Snoopy couldn’t be a regular dog.”