|

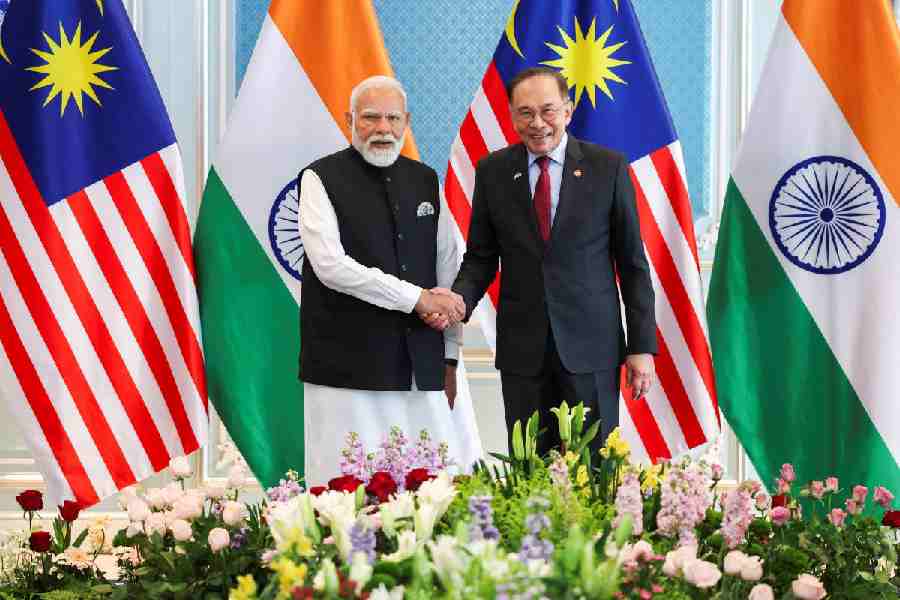

Geneticist Kunal Ray (see pic) has been chasing altered genes all his life. About 10 years ago, Ray, a scientist at the Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (IICB) in Calcutta, had an unusual visitor at his lab.

The visitor, Swapan Samanta, was a practising doctor. He wanted to know whether Ray, who specialises in the molecular genetics of human diseases, would be interested in working on a peculiar problem he encountered during his medical practice in Bankura district. Much to his surprise Samanta found that Bankura, one of the most backward districts in West Bengal, had an unusually high number of people who suffer from a disorder that the medical community knows as oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) — albinism for short.

People who suffer from albinism — they are called albinos — have unusually light skin and hair as well as vision impairment of varying degrees. For albinos, exposure to sunlight without some sort of protection would mean skin problems, which sometimes lead to skin cancer. More importantly, many of them have such limited vision that legally they are considered blind.

“Samanta wondered why albinos are found in such high numbers in Bankura and wanted us to find out,” Ray recollects.

Ray and his colleagues at the IICB, a laboratory under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), took up the challenge. The initial studies were concentrated on an ethnic community called Tili to which most albinos in the district belonged. The scientists found that the community, which constituted nearly 13 per cent of the district population, had one of highest rates of albinism anywhere in the world.

Albinism, which is estimated to affect 1 in 17,000 all over the world, is caused mainly by a defective synthesis of the pigment melanin, which is critical in imparting colour to skin, hair and the iris of the eye. Melanin is synthesised from an amino acid called tyrosine. In India, a defect in the tyrosinase gene —resulting in impaired production of tyrosine — is responsible for nearly 50 per cent of the cases of albinism. Such people will have either no melanin or only some.

In the rest of the cases, other genes are implicated as well. In fact the IICB team, in a paper published online in the journal Gene last week, reported on a number of genes implicated in albinism in the Indian population.

|

| Scientist Kunal Ray |

These genes are mainly involved in the processing of the pigment melanin. But their contribution to albinism is relatively less known, says Ray, who retired from the IICB in July this year.

The scientists found that in the Tili population there is a mutation in the tyrosinase gene. One reason for the community having a high number of albinos is that they practise endogamous (within the community) marriages, just like many other Indian ethnic groups.

“A person carrying a single copy of the mutation would not have the disorder but when two such carriers marry, there is a 25 per cent chance that their child would carry both the mutations,” says Ray.

Marriages with people outside the community would mean a decrease in albinism in the area. The practice of marrying strictly within the community, that many ethnic Indian communities follow, increases the probability of genetic disorders such as albinism. “There hasn’t been any epidemiological study to unearth the extent of the problem in the country,” says Mainak Sengupta, who is currently pursuing postdoctoral studies under Ray. So the extent of the problem is unknown.

“Unfortunately, just like any other inherited disorder, the propagation of albinism in a population is dependent on the reproductive practices in a specific community — the higher the level of endogamy the greater the chance of a genetic disease including albinism,” says Susanta Roychoudhury, an IICB scientist not connected to the study. Roychoudhury and Ray have earlier worked together on a CSIR project to ascertain unique genetic variations in the Indian population.

Albinos have trouble living a normal life not only because of their severe vision impairment but also because of their extreme sensitivity to sunlight. No one in the India can have a normal life if they cannot go out in the sun. Also, albinos are very susceptible to skin cancer. There is no known cure for albinism and the goal is to contain the disorder. Identifying the carriers and making sure that they do not marry other carriers can go a long way in doing that. In ethnic groups where marriage within the community is common, prior knowledge could help select appropriate partners so that the disorder is not passed on to the next generation.

Currently, however, such genetic screening is rarely practised in India. In fact only one hospital, the Arvind Eye Hospital in Madurai, offers such screening. In addition, some hospitals in the country, including the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, offers a prenatal genetic screening, which could pick up signs of albinism.