Serene. Graceful. Composed. Those were the words that came to my mind when I saw Jane Goodall face to face. It was a sunny winter morning at the Calcutta zoo. The date was January 19, 2007.

Goodall, then in her seventies, was in the city to deliver a talk at a wildlife film festival; in the lineup was a documentary titled When Animals Talk, We Should Listen, which featured Goodall. But that morning she had decided to make an impromptu visit to the zoo.

As soon as I received the call from the British Council, the official organisers of Goodall’s India visit, I headed out. Those were pre-social media days but by the time I reached, the place was already milling with journalists and environmentalists eager to meet the woman who had challenged what it meant to be a scientist in the wilds of Africa and beyond.

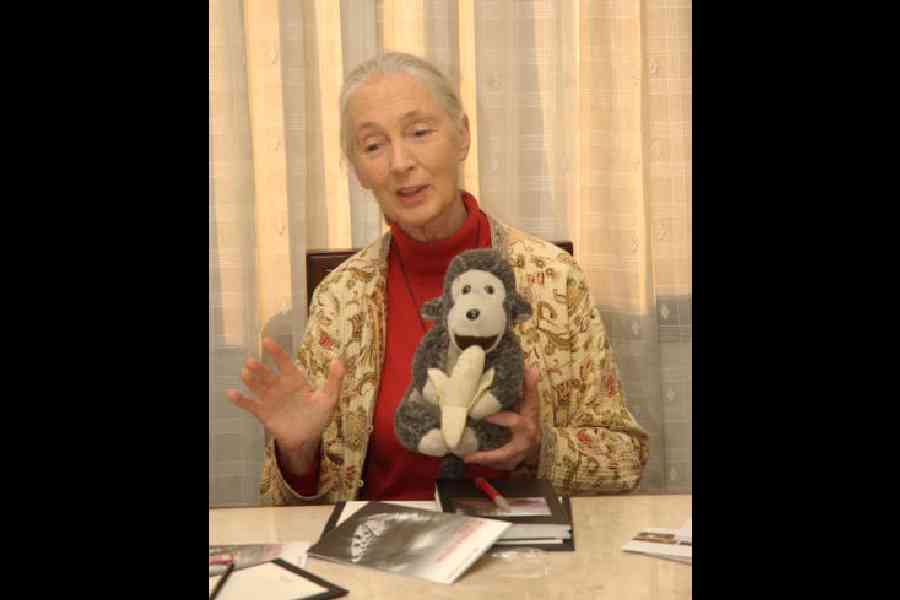

Jane Goodall, a British anthropologist at a programme in Calcutta

The primatologist started her tour of the zoo with the enclosure for the chimps.

Babu, the male chimp, was sitting alone on an island surrounded by a moat, while his partner, the female chimp Rani, was shut in a cage. “Why are they not together?” Goodall asked. “They look so bored and depressed.”

The male chimp was urinating, directing the stream into his mouth. Goodall turned to us and explained that those were classic symptoms that he was “listless and unhappy”. She suggested that the zoo authorities introduce low cost innovations such as climbing structures with poles, raised platforms and ropes that would provide stimulation for the apes.

“A very simple enrichment is to throw handfuls of food grains, nuts and raisins onto the grass. The chimpanzees spend long hours searching in the grass,” she said. “It would not be expensive to install an artificial termite mound that can be filled with a variety of substances,” she added. She spoke about the Chimpanzoo programme at the Jane Goodall Institute, a global conservation organisation headquartered in Washington D.C., US.

Goodall was best known for her research on chimpanzees at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. In 1960, she was the first to discover that chimpanzees made and used tools. She observed chimpanzees using twigs and grass to “fish” for termites, a behaviour that redefined humanity’s understanding of tool use and intelligence. Previously, only humans were thought to possess such abilities. Termite fishing involves selecting, stripping and inserting a twig into a termite mound to extract nutritious termites, which are a valuable part of the chimp diet.

Palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey had recruited the 25-year-old Goodall to study wild chimpanzees in Gombe. Leakey believed that studying the closest living relatives of humans would eventually reveal insights into the behaviour of early human beings or hominids, something fossils alone couldn’t do.

Goodall, who did not have a formal university education, was hired by Leakey as a secretary because he was impressed by her power of observation and an open mind.

Goodall broke with the scientific convention of using numbers to identify animals in the wild and assigned them names instead. She named a male chimpanzee with facial hair David Greybeard. While this upset some seasoned scientists, today it’s a common practice to use animal names in such research. The primatologist was also among the first to prove that animals had emotions, empathy and culture, traits believed to have been reserved solely for humans.

Her empathy for animals was palpable as she stepped from one enclosure to another at the zoo in Alipore that year. “I feel sad to

see so many animals alone,” she said.

Lack of adequate educational materials for visitors and “lax supervision by the zoo staff” also irked her. She was particularly disturbed when a large group of schoolboys — aged between 15 and 16 years — jeered at, taunted and shouted at the lions and leopards in their solitary cages while the accompanying teachers did nothing to stop them. “It’s the duty of the zoo authorities to educate people on the captive lives of animals and their natural habitats so people can care more for and respect animals,” she had remarked.

Finally, she expressed shock at the nature of the enclosures occupied by the lions and leopards. She urged the authorities to address their solitary confinement. Goodall asked, “Why do leopards have no way of moving off the ground? They are not used to spending time on the ground.”

In the evening of January 19, 2007, Goodall delivered a lecture at Nandan where she clarified that she wasn’t against keeping animals in zoos as long as they were well taken care of. “People are cutting down trees, there’s not enough forest cover and animals are being hunted. Chimpanzees are being captured for meat. At the zoo, the animals will at least be safe. But, of course, you have to make the zoos habitable for the animals,” she said.

Goodall proved it was possible to have a scientific bend of mind as well as empathy.

P.S: As a young girl, Goodall loved to read about Tarzan’s adventures. And the story goes that that is how she started to dream of going to Africa and living among the apes. Goodall, who had a crush on Tarzan those days, thought she would be a better partner for him than the Jane he chose. She famously said: “Silly man. He married the wrong Jane.”