The first-generation iPhone was announced by Apple co-founder, the late Steve Jobs, on January 9, 2007, at Macworld. Later that year, the phone went on sale, ushering in a new era — the era of the smartphone. Everything changed, including the world of photography.

Suddenly, people had one more reason to hit the streets — to take photographs. iPhone is the tool that made street photography easy. The best way to increase your confidence is by stepping outside and giving it a try. You will definitely discover new stories about your city. At least I did. Here are three stories about Calcutta, captured on iPhone.

Easy to miss

Besides the usual suspects — the Howrah Bridge or the Victoria Memorial — tourist guide books often have a picture of the General Post Office, a handsome building on the west side of Dalhousie Square at the corner of Koila Ghat Street, being a portion of the site of the old Fort of Calcutta.

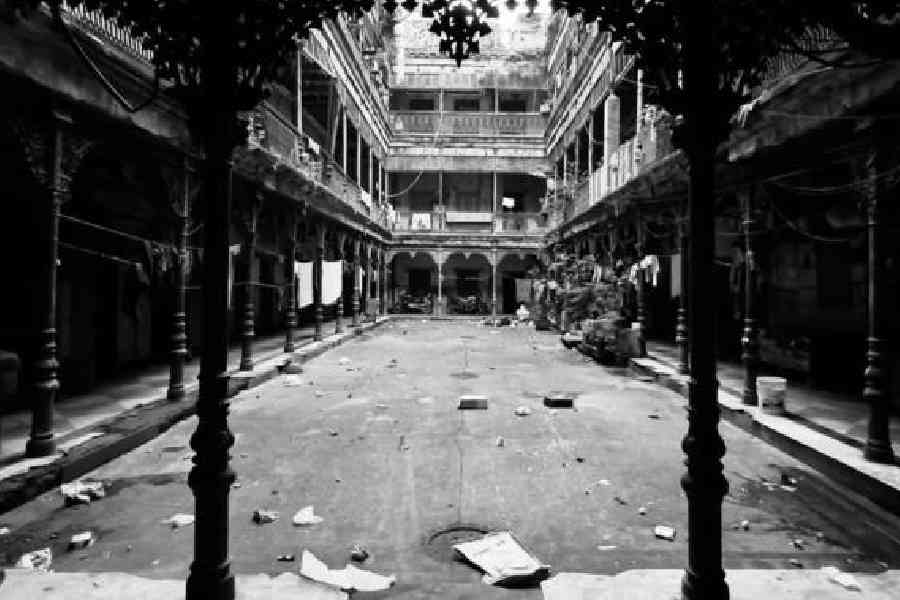

A 'mess bari' on Pathuriaghata Street. Picture: Mathures Paul

Designed by Walter B. Granville, architect to the government of India, it was opened to the public in 1868 and cost Rs 630,000. After the eyelids feel heavy faced with tall Corinthian columns, walk along Koila Ghat Street for a couple of minutes to find this gem hidden by its own obviousness, which happens to be the office of the director of accounts (postal).

Probably a distortion of “qila” or fort — meaning the Old Fort William — the building on Koila Ghat Street wears an empty look if you can make it on a weekend before 8am. This part may have housed the old import and export warehouses.

Early descriptions of the Fort can be found in the writing of Captain Alexander Hamilton, a trading seaman who had visited India in early 18th century, published in 1727 “a new account of the East Indies” in which he offered a description of Calcutta. “Fort William was built an irregular tetragon of brick and mortar called puckah, which is a composition of brick-dust, lime, molasses, and cut hemp, and, when it comes to be dry, is as hard and tougher than firm stone or brick.”

The Fort stood on the bank of the river, which flowed along what is Strand Road. Its bastions and buttresses enclosed the space lying between Fairlie Place and Koila Ghat Street. Except for the church and the hospital, all official buildings were within the Fort.

When ‘mess’ comes home

Decades ago — when most household TVs were as black-and-white as the movies made in the 1950s — I saw the always-confident Uttam Kumar and the ever-versatile Suchitra Sen brought the small screen alive in a film set in Annapurna Boarding House, a ‘mess bari’ for working men. Sen’s Romola arrives to turn the ‘mess bari’ upside down as well as the life of matinee idol’s character of Rampriti. That’s it. I thought I knew the meaning of ‘mess bari’.

The Bengali coinage — ‘mess’ as in the place where soldiers socialise, eat and live while ‘bari’ is house — became popular by mid- or late-19th century when such places popped up across north and central Calcutta.

Of course, you may have heard of a dilapidated ‘mess bari’ on Kedar Banerjee Lane, once home to humorist Shibram Chakraborty. Or find 66, Harrison Road (now Mahatma Gandhi Road) where Byomkesh Bakshi creator Saradindu Bandopadhyay lived. And so did Jibanananda Das for a few years.

That brings me to Pathuriaghata Street to an entrance like any other, a mess-y environment like any other but walk a few steps into the building and plenty of cast-iron greets the camera. I can well imagine the location in a 1950s Bengali film. But a man carrying a bucket of water abruptly says “Cut!”…. uh, actually: “O dada.” The black-and-white movie ends.

Waste land

In 2020, tuberculosis claimed more than 1.5 million lives worldwide, yet we don’t talk about it. Calcutta was once miles ahead when it came to tackling the well-known killer and then politics put it on a slippery slope.

iPhone 16e can handle all the Apple Intelligence tasks, including Visual Intelligence

A stone’s throw away from Parshwanath Temple stands one of India’s early answers to TB — Balananda Brahmachari Sebayatan (an institution of Daridra Bandhab Bhandar). It probably came up after the iconic Dr Kumud Sankar Ray TB Hospital in Jadavpur and, in its early days, received donations from some of Calcutta’s leading families.

Now shut for decades, the hospital also had a clinic called Chittaranjan Databya Chikitshlaya. Outside are two marble plaques featuring the names of some of the donors — Jatindranath Maitra, Sasi Kumar Sengupta, Gour Mohan Pyne, Bepin Behary Ghosh, Kedar Nath Auddy, Badridas Goenka… you get the picture.

The hospital was in full swing even till the 1970s alongside GK Khemka Chest Clinic and Hospital. There was a time when food was prepared in large quantities to ensure patients were well taken care of.

The magnitude of the problem has been known for a long time and in a report on the Municipal Administration of Calcutta in 1907, it was pointed out that the proportion of deaths from TB to the total mortality worked at around 10 per cent. The post-mortem examinations of Captain Leonard Rogers at the Medical College Hospital in Calcutta also highlighted the severity of the disease.

Balananda Brahmachari Sebayatan on Raja Dinendra Street

At that point, large, well-ventilated wards were the need of the hour and as a subsidiary measure, the prevention of spitting in the streets had to be observed. Sadly, we are yet to tackle all spontaneous callisthenics of the mouth.

Politics, over decades, put a spanner in the works and shutters slowly came down because of lack of funds and collaborations that did not work.

There have been talks of revival, but all I have been seeing over the decades are trees easing into the cracks of the building. It’s not the trees that are the problem but the very roots of the healthcare system that need to be tackled.