Contrary to what most of his peers believe, scientist Raghu Murtugudde is still not convinced that the world is in for the strongest ever El Nino - an abnormal warming of waters in the Pacific Ocean which disrupts weather across the globe - this year.

This India-born professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Maryland in the US has been trying to understand whether science can reliably forecast El Nino much in advance so that the regions where this unusual phenomenon brings extreme weather conditions have time to make adequate preparations.

Recently, Murtugudde - who did a BTech from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, more than 30 summers ago - together with his Chinese counterparts showed that certain wind bursts that frequently originate in the far western Pacific and blow eastwards - called westerly wind bursts (WWBs) - may be key to accurately forecasting El Nino. The study that appeared in the journal Nature Geoscience early this year suggests that observing WWBs could help predict the severity of an El Nino.

"There is no indication yet that this El Nino will develop into one of the strongest in the recent decades as many have suggested. We may need to wait for a few more weeks before we jump to any conclusion," Murtugudde told KnowHow from Pune on the phone. Murtugudde is currently a visiting faculty member at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Pune.

About 10 days ago, forecasters at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said that the currently developing El Nino in the Pacific Ocean is intensifying and may eventually turn out be one of the strongest on record. Though El Ninos have been occurring for nearly 10,000 years, scientists have been able to study them only since the advent of weather satellites. Since then, there have been two strong El Ninos - in 1982-83 and 1997-98.

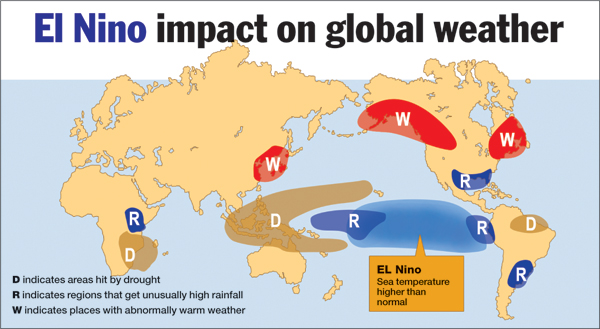

The impact a strong El Nino can have on the weather varies from region to region. While it reduces rainfall drastically in countries like India and Indonesia, and triggers drought-like conditions in Australia, it can cause flooding in South American countries and on the West Coast of America. In fact, California, which has been reeling under a drought for the last four years, is looking forward to bountiful rains if El Nino develops.

Significantly, the India Meteorological Department (IMD), fears that El Nino may hit the ongoing monsoon season. It has forecast lower than normal rainfall this year.

It is important to know how an El Nino works. Weather patterns are always a product of a complex interplay between sea-surface temperatures and atmospheric conditions.

In normal years, tropical trade winds (which bring monsoon clouds to India) blow from the east to the west across the Pacific, pushing warm surface water from South America towards Australia and Asia. As the warm surface water moves westward, cold water is comes to the surface through a process called upwelling.

But every few years these trade winds weaken, causing the ocean surface to remain warm. The pool of warm water in the western Pacific moves slowly towards South America. The warm waters hit the South American coast around Christmas, prompting the Spanish settlers in the 19th century - who thought this anomalously warm water a gift from God - to name it El Nino, or "the Christ Child".

El Ninos occurs every two to seven years. "Our studies in the past have shown that all El Ninos originate the same way," says Murtugudde. But what intrigued scientists was that while some of these peter out early, others continue to develop over a long time and affect weather patterns over a wide-ranging area.

Almost all global weather events have a feedback mechanism and some of them may be playing a role in limiting the extent of El Nino, says Murtugudde. "For all you know, even the monsoon may have an impact on El Nino," he says.

In this context, what he and his Chinese collaborators have found about WWBs is significant. Their study found that WWBs, which blow in the opposite direction of trade winds, weaken the latter and thus help warm waters to move much beyond the International Date Line. "What we have found is that when WWBs coincide with a developing phase of El Nino, there are good chances that it may be a strong El Nino. Surprisingly that is not the case this year. At least till now," says the University of Maryland scientist.

The Indian monsoon's connection with El Nino too is very complex. While the country suffered bad monsoons in many El Nino years, in some it received very good ones too. Of late, meteorologists have discovered that a warm pool (spread over thousands of square kilometres) in the Indian Ocean called the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), limits the impact of an El Nino on the Indian monsoon. When the IOD is absent, El Nino will affect the quantity of rainfall.

"Considering that this year we have a strong El Nino developing and IOD is absent, in all likelihood we will have below normal rainfall," says A. Suryachandra Rao, a scientist at the Pune-based Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and an associate director of the National Monsoon Mission, an ambitious project launched by India to improve monsoon forecasts. This year's IMD forecast estimated that the monsoon rainfall would be around 88 per cent of the long-period average of 880 millimetre.