This is Dr Graham Roger Serjeant's 21st visit to India. As we catch up with him in a hotel in central Calcutta - where he is on a brief stopover before he begins a trek to the deep forests of central India - we find that the British researcher is raring to go at seven in the morning.

Dr Serjeant is no ordinary tourist - he is an expert in sickle cell disease and his visits have led to an improvement in the quality of life of tribal communities in central, western and southern India, among whom this disease is usually found.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a severe and hereditary form of anaemia in which the red blood cells become rigid and crescent shaped, resembling a sickle. Because of its rigidity, the cells cannot travel down tiny blood vessels, so far-flung organs are deprived of oxygen. Over a period of time, the organs get affected and may even fail.

The disease is usually found among communities that originated in ancient Africa. It is now widespread, affecting people not only in Africa but in West Asia and central India. The "poor man's disease" which kills thousands of infants every year takes a back seat when it comes to research into treatments for diseases.

Dr Serjeant has dedicated 50 years of his life to SCD. His Indian sojourn began in 1983 in Sambalpur, Odisha. "I make it a point to visit the country at least twice a year," says the 78-year-old doctor.

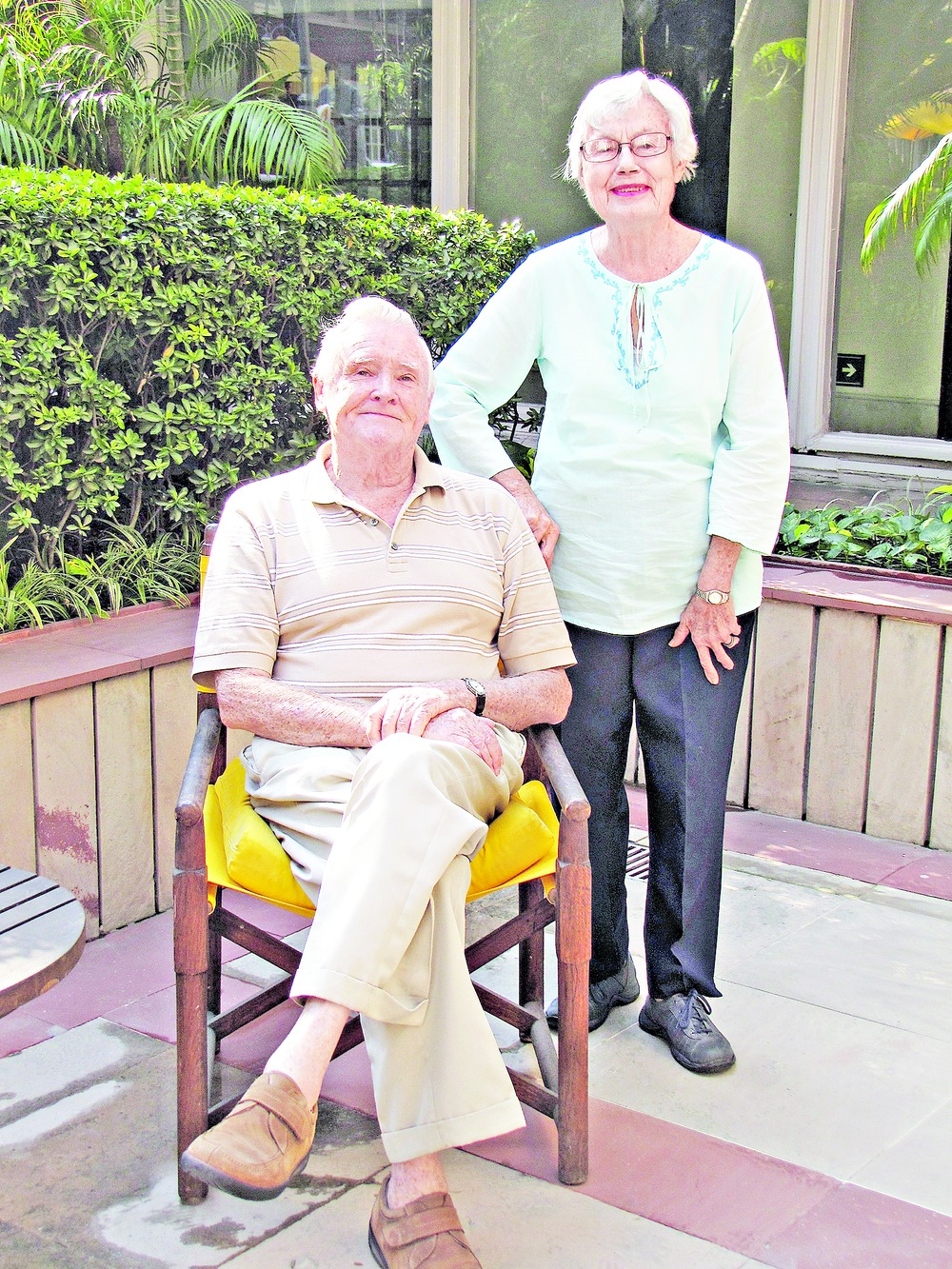

His wife - Beryl Elizabeth Sergeant - joins us. "Meet Beryl, a medical technologist, who innovated low cost diagnostic tools for SCD suitable for Indian patients," he says. She's also co-authored seminal books on the disease with him. Dr Serjeant rewrote many textbooks on SCD and redefined the characteristics of the disease.

It all started with his visit to Uganda in 1960 for clinical training. He found that the nature of the disease was widely different from what the textbooks described. He was then studying at Clare College, Cambridge, and London Hospital Medical School for his medical degree. "I realised that those interpretations were heavily biased towards hospital-based patients in Britain," he explains.

He discovered that the disease was far more widespread than estimated, and also went largely undiagnosed. "Moreover, the cases varied, ranging from death in early childhood to mildly affected patients living up to the age of 80," he says. Dr Serjeant understood that that the extreme variability implied that other factors, both genetic and environmental, influenced the extent of the disease.

To study SCD more closely, he chose to take a job as a clinician in Kingston, Jamaica, where the disease is quite widespread. He travelled extensively across the island, following up patients long lost to clinics in a mobile van. The observation changed the concept of SCD and confirmed that treatment had to be tailor-made for each patient, depending on specific symptoms. It also made the case for a large-scale study of the disease, based on detection of babies born with SCD.

"This was partly possible because of Beryl who innovated low-cost methods for the diagnosis of the disease on samples taken from the umbilical cord of a newborn baby," he says.

This was a landmark achievement since it was believed at that time that it was not possible to diagnose SCD at birth. Once the diagnostic methods were perfected at the Victorian Jubilee Hospital in Kingston, Jamaica, Dr Serjeant initiated the Jamaican Sickle Cell Cohort Study - the world's first extensive newborn screening for sickle cell disease.

The groundbreaking study began in 1973 and ended on December 28, 1981 - screening 100,000 babies in that period. The unit used the cohort to help map disease progression from birth, and improved care for those with the disease.

"A great deal was learnt about the evolution of the abnormal haematology of sickle cell disease and its relationship to clinical features," he says.

It was found that early mortality is often caused by complications in the spleen, chest, abnormally low haemoglobin and blood poisoning (pneumococcal septicaemia). "As these syndromes were addressed to varying success, many of the affected children survived to reach adulthood," he adds.

The Jamaican cohort study offered unique opportunities for studying every aspect of the disease including its social and psychological perspectives. The study also inspired formation of many such groups across the globe.

For over three decades, Dr Serjeant has collaborated on the development of SCD treatment and research in Brazil, Europe, Africa, the Arabian Gulf and India. "Since the SCD gene appears to have developed on at least three different occasions in Africa and at least once in eastern Saudi Arabia or central India, the disease occurs against a variety of different genetic and environmental backgrounds."

SCD is common among tribes in central, western and southern India. Although the Indian variety is milder compared to the African variety, morbidity and early death are frequent here.

"Newborn screening programmes for SCD have recently been initiated in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Odisha and Chhattisgarh and monitoring these birth cohorts will help understand the natural history of the disease in India."

According to him, diagnostic and treatment modalities used in Western countries or even in some African countries are inappropriate and expensive in the Indian setting. "You need programmes tailor-made for Indians. There's no one-size-fits-all solution to SCD."

Dr Sergeant makes special mention of dedicated doctors such as the late Dr Bimal C. Kar in Sambalpur, Odisha, and Dr Jyotish Patel in Bardoli, Gujarat, who have made a difference in India.

"The need of the hour is a large number of well-trained doctors to treat people in India's hinterland," Dr Sergeant says. But then medics like him - ready to dedicate their lives without expecting much in return - are not easy to find.