|

|

|

My father was a tough wiry Jew from the Bronx. He was a small man with Popeye forearms and hands strong enough to crack walnuts just by squeezing. He was my hero. No one was as strong, honest, smart, or brave as he. He was a plumber and his business was in the rotten tenement buildings in Harlem and the South Bronx where we lived. It was nothing like being a plumber in Palo Alto where I live now. The buildings were dirty, smelly, full of rats, and dangerous. A good part of his business was sewer and drain cleaning which is filthy work. From the age of 13 I worked with him after school, Saturdays, holidays, and all summer. The family plan was for me to take over the business sometime after I finished high school.

The truth was that I hated sewer cleaning and wanted to get out. Coming from a working class family where nobody had gotten past the 5th grade, I had no idea what else to do. But my father had an idea. He wanted the two of us to go into the heating business. This meant big furnaces and hot water boilers for the tenement buildings. He thought that I should go to college and learn heating engineering. This seemed better than the sewer, so in 1957 I enrolled in the City College of New York as a freshman-engineering student. CCNY was a subway college and it was free.

The first year was great. It was all mathematics and physics. Physics was completely new to me. I had no idea that a person could become a physicist and make a living, but I was good at it and it was fun. I did well those first two semesters. By that time I was married with a small baby and I still worked whenever I could. I was enjoying life. But then came my first real engineering class. It involved making drawings of mechanical parts like gears, cogs and that kind of thing. In those days there were no computers and you did the drawing with India ink and a kind of pen invented by the devil himself, a so-called ruling pen. Using it was a trick I simply couldn’t master and so by the time the rest of the class had completed three drawings I was halfway through the first.

I still remember the professor’s name ?Harold Rothbart. Toward the end of the semester HR came over to my drawing table and said “Susskind, you are failing this class.” This was bad news. So far I had done very well in college and I was on schedule to graduate and go to work full time to support my little family. Then he said that he would pass me under one condition, namely, that I drop out of engineering. I said “What am I going to do? I’ve got to become an engineer so that I can build heating systems.” HR looked concerned and then said, “Susskind, you’re a very smart kid. You should become a scientist. Go talk to the science departments and find out if they will take you.”

To me, at that time, science meant white lab coats and test tubes. So I went to the chemistry chairman. He looked at my record and said that since I had not taken any chemistry courses it would take me at least an extra year-and-a-half to graduate. That was a non-starter. I had to get to work.

Next I tried math. I had gotten an A in calculus, but I still didn’t have enough math credits to graduate on time. So finally I went to the physics department. I talked to a guy chomping on a stinking cigar. His name was Harry Soodak and he became my physics mentor and friend. We are still good friends to this day. He said that I could probably get through in time if I did some extra studying in the summer.

I figured to myself that I was smart enough to find out how boilers and furnaces worked on my own, and I would graduate with a physics degree. My father would never know the difference. But things don’t always work as planned. I fell in love with physics and discovered that it was still a living, breathing science and that it was possible to be a physicist. For the next three years all I wanted to do was learn physics and try my hand at doing it myself. With Harry’s help I gradually became a physicist, a beginner to be sure, but a physicist nonetheless. I knew I could not go on being a plumber.

But I would have to break my father’s heart. I had to tell him. So I worked up my courage, drove over to his house with my wife and baby, and said, “Ben (my father’s name was Benny), I’ve got to tell you something.” I was scared, but I blurted it out. “I’m not going to be an engineer.”

The tough guy looked at me and said, “What the ? do you mean, you’re not going to be an engineer? What are you going to be ? a ballet dancer?” I said, “I want to be something else, a physicist” “Physicist? Physicist? What the hell is a physicist?” I really wanted to say, ha ha, I’m kidding. But I held my ground and answered “It’s a kind of scientist.” He had never heard of physics before and he responded, “Get out of here ? you ain’t going to work in no drug store.” He thought I had said pharmacist. I was not sure that I could explain so I took a shortcut. I said “a scientist like Einstein.”

“Einstein?” he said. “Yeah, Einstein.” For a full minute he stood silent, in deep thought. Then he said, “Are you any good at this stuff?” I knew that I was and I said so. He got quiet again for 15 or 20 seconds and then pointed a short piece of pipe at me. “Look Sonny” (that’s what I was called at that time) “you ain’t gonna be no plumber. You’re gonna be a physicist. Like Einstein!” Then my mother, who was listening started to cry. “Oh my god, he won’t be able to make a living. The baby won’t have enough to eat. They’ll starve.” Ben turned around and shot her an angry look. “Shut up, he’s gonna be Einstein.”

Oddly, as soon as I discovered physics I stopped doing well in college. All I wanted to do was physics, but CCNY rightly wanted me to get a full education: English, Biology, History, German etc. The conflict was resolved in favour of physics.

I immediately proceeded to fail every non-physics course for the next couple of years. But fortunately, Harry Soodak and a couple of other physics professors thought enough of my abilities to convince Cornell University to accept me as a graduate student ? a graduate student who hadn’t graduated. Three years later I had a freshly minted Cornell PhD in physics, but still no bachelor’s degree. Then one day, the year was 1966, after I was already an assistant professor at the Belfer Graduate School of Science (Yeshiva University) in New York, I received a large envelope from CCNY that contained a diploma and an updated transcript. All the failed courses had been eliminated, but I noticed that I had been credited with proficiency in a number of subjects including plumbing.

I loved being a professor at the Belfer Graduate School. It was an extremely stimulating place full of great physicists like David Finkelstein, Yakir Aharonov, Joel Lebowitz, Eliot Lieb, Roger Penrose, Freeman Dyson, and Al Cameron. It was during that time that I co-discovered string theory. But the good times at Belfer lasted for only 10 years. Bad economic times in the 1970s undermined the economic base of many universities, but none so dramatically as The Belfer School. It went belly up and I had to trundle off to Stanford University where I have been a professor since 1978.

The intellectual life of theoretical physicists is a strange one. Driven by curiosity about the mysteries of the physical world, we spend most of our time confused and frustrated by questions that just won’t yield ? questions like “Why is it that quarks behave like miniature ‘tar babies’ stuck together by some sticky substance that just won’t let go?” or “Are the bits of information that fall into a black hole destroyed by violent tidal forces at the black hole’s singularity, or are they radiated back into the world when the black hole evaporates?”

For me, most of the time has been spent going in circles over paradoxical conflicts that I am unable to resolve. But I have been luckier than most. From time to time, the confusion has been punctuated by brief periods of discovery ? Eureka moments ? when I was able to break through some problem and see some new pattern. The discovery of string theory was like that and so was the discovery that the world is a kind of quantum hologram. Both of these ideas are now main-stream physics but I had the good luck to recognise them early on. These brief periods of illumination are what theoretical physicists live for.

I’ve also been very lucky to be part of the incredibly interesting society of theoretical physicists and had such extraordinary friends as Richard Feynman, Stephen Hawking and countless less famous but equally fascinating colleagues. We live in a unique and amazing world of ideas that I wouldn’t trade for any other. All I can say is, “Hey diddle dee dee, a physicist’s life for me.”

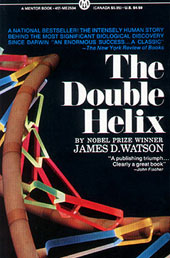

I have often been asked if there was any book that influenced me to become a physicist. I only recall one and I don’t remember when I read it. It may have been high school or even early college, but it left a very strong impression on me of the romance of theoretical physics. It is probably the place that I first learned who Einstein really was and what he had done. The little book was George Gamow’s wonderful One Two Three Infinity. At the time I would have been amazed to know that Gamow was more than a writer of clever short popular books. He was the father of the modern Big Bang theory of the Universe. Later in life I came to greatly value some other popular science books. I’ll list them in no particular order. The Double Helix by James Watson, Dreams of a Final Theory (Steven Weinberg) and The Selfish Gene (Richard Dawkins).