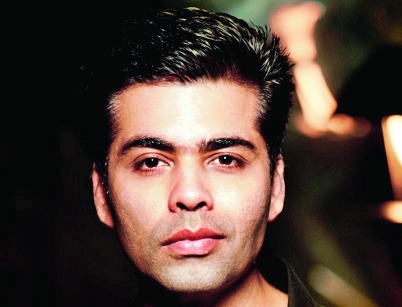

AN UNSUITABLE BOY By Karan Johar, (with Poonam Saxena) Penguin, Rs 699

Akira Kurosawa began Something like an Autobiography with a story about a miraculous ointment for cuts and burns sold by itinerant peddlers in pre-war Japan. The making of this medicine was said to involve a ten-legged toad placed inside a mirror-lined box. At its own bizarre reflection the toad broke into an oily sweat, which was collected and simmered on a fire for many days so that it transformed into this 'magic' medicine. "Writing about myself," Kurosawa said, "I feel something like that toad in the box. I have to look at myself from many angles, over many years, whether I like what I see or not. I may not be a ten-legged toad, but what confronts me in the mirror does bring on something like the toad's oily sweat."

One wishes that Karan Johar had expended some thought along similar lines as a courtesy to his readers. Johar's 360-degree view of himself begins thus: "Today I finally feel liberated... I don't want to be this person who is bound by principles, morality or reality, someone who has to conform to any kind of societal rules." His aim is to be objective about his life and to express opinions without being obliged to defend them. The reader is informed that he is a funny and "overly-sensitive" person who loves luxury and old Hindi film music. The three most important men in his life are Shah Rukh Khan, Aditya Chopra, and his old schoolfellow and Dharma CEO, Apoorva Mehta. He is "not an immensely politically motivated person" but that doesn't bother him because he is unmoved by the "stupid intellectual banter of people who know nothing, and can't create anything themselves". Far from breaking into a sweat, then, Johar's voice throughout the 200-odd pages of his memoirs reeks of self-satisfaction. This book is nothing like the extravagantly glamorous experiences he offers his audience on celluloid, although it uses the foolproof hooks of gossip and scandal in its marketing. It is an insipid monologue spoken to a journalist that promises much but delivers little of substance or value.

The narrative is roughly chronological. The two opening chapters introduce Johar's parents' backgrounds and describe his school and college years. The young boy's low self-esteem and body-image issues, his dramatic breakthrough from being "mediocre" student to sought-after school debate champion, the secret coaching he underwent to develop a baritone and his love of Hindi cinema are referred to. Successive chapters are thematically organized around high points in his early career. Beginning with his experience in assisting Aditya Chopra in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, these continue till after his father's death and the taking over and consolidating of Dharma Productions. The concluding chapters contain musings on Shah Rukh Khan, friendships and estrangements (in which Kajol figures prominently), love and sex, Koffee with Karan, his role in the AIB Roast, midlife angst and a final criticism of Bollywood today. It is a great pity that Johar does not take his own advice when he exhorts the young blades of Bollywood to open their hearts to the public. This book conveys no sense of personality apart from the Olympian indifference that Johar claims to have achieved at the present stage of his life. It is a careful voice that speaks to us, correct and distanced, achieving neither the drama of his films nor the irreverent wit of his public persona. Indeed, for a man noted for his wisecracks, the book is remarkably unfunny. Johar serves up high emotion in dry prose. Complex and fraught relationships, deep attachments and profound hurt, lose all sympathetic resonance in the blanket monotony of the narrative.

Inconsistency is a symptom of this book. For instance, Johar talks about his first sexual encounter, which is said to have taken place in New York on page 169, in London on page 170, both at age 26. He never "grew up with film people" but did spend his time "in the company of star kids". Such inaccuracies matter little, indeed can add richness to the telling, if structured with awareness and insight. Memory, after all, is a funny thing. But Johar takes his memories far too seriously.

In spite of nicely-done photographs, good quality paper and a hard cover binding, An Unsuitable Boy seems put together without care. A quote from Aditya Chopra on page 41 is ascribed to Shah Rukh Khan on the back blurb. What prompted Johar to write his memoirs? Why and how was the co-author chosen? What was the writing process like for both authors? We have no idea. Poonam Saxena is an experienced journalist who has produced a competent translation of Dharamvir Bharat's Gunahon Ka Devta. Is it editorial policy that suppresses the voice of an intelligent and articulate writer in this publication? One suspects that, if allowed a freer hand, her intervention might have at the very least saved the book some grammatical errors and tautological tiresomeness.

Yet, although many things are very wrong about this book, Karan Johar's autobiography emerges as an unwitting testament of the great sadness that underpins privilege in a fractured world. Without meaning to, it tells the tragic story of a seller of human emotions who, in his fight to rise above unhappiness, is beggared of the ability to articulate any of his own.