The Union budget is a many-splendoured thing. So is a state budget, but it is the Union budget that enjoys the lion’s share in the splendour. The one that was presented yesterday has, in fact, been titled the ‘budget of the century’ on account of the fact that the world as a whole has been writhing under a pandemic for more than a year now.

That the pandemic has dealt a hard blow to our economy is obvious from the published figures. Around this time a year ago, the Union budget had predicted a fiscal deficit (the government’s outgoings minus incomings) of 3.5 per cent of GDP for the year April, 2020 through March 2021 (FY2021). The pandemic ensured that the government’s outgoings far exceeded its planned incomings. As a result, the revised fiscal deficit stands out to be around 2.72 times higher at 9.5 per cent. The enormous gap has forced the government to borrow from the market. In fact, according to the budget figures, 36 per cent of expenditure will be met from borrowing and 27 per cent from direct taxes. The Economic Survey merrily suggests that this is no cause for worry, since loan repayment will be ensured through higher economic growth in the future.

Leave alone growth, India’s real GDP has fallen over the past year by 7.7 per cent. However, in the year starting April 2021, the economy is projected to register a positive growth rate of 11 per cent. This implies a net positive growth of 3.3 per cent, taking into account the 7.7 per cent growth that will be needed to simply break even. Viewed from the point of view of employment-generation, the 7.7 per cent positive GDP growth will merely re-employ those who lost their jobs due to the contraction and new jobs will be created on the basis of the net positive growth of 3.3 per cent alone. The government has announced a slew of infrastructure projects to revive employment. If these succeed, they will probably re-employ the job losers. What will happen to the new entrants in the job market is not clear.

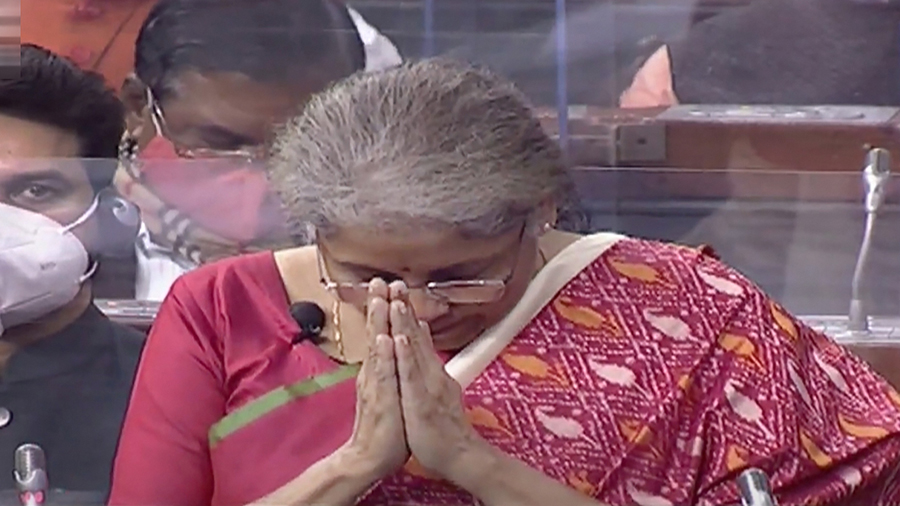

Going back to expenditures, the finance minister started off her speech emphasizing the succour to be received by the health sector. The budget outlay for “Health and Wellbeing”, she said, is Rs 2,23,846 crore in the current budget as against the previous year’s Rs 94,452 crore. This being a 137 percentage increase is a heart-warming assurance for India where health is one of the most neglected sectors. The budget calculations, though, are based on an estimated GDP of Rs 22,287,379 crore for the coming year. It is easy to see that the much advertised ‘Health and Wellbeing’ figure of Rs 2,23,846 crore is only 1.004 per cent of the estimated GDP. The euphoric figure of 137 per cent increase needs to be analysed a little more carefully. Similar questions may come up in connection with education and other major generators of economic growth.

A budget document contains too many details, and it is not possible to address each one of them in a short span of time. Let us, however, take up one more issue that concerns the tax-paying public. Tax-paying senior citizens above the age of 75 will not need to file income tax returns as long as they depend on pension and interest incomes. “The paying bank will deduct the necessary tax on their income.” This is wonderful news, especially since the lay public has been subjected to enormous tax harassment over the years. Aged people may rest at ease now, except for the fact that a reasonably large subset of them earns incomes from other sources as well. For example, not all senior citizens are pensioners. They may be freelancers and not regular employees of any organization. Tracking such incomes may not be straightforward. Hence, the simplification of ‘no return submission’ may well be balanced off by compulsory declarations unless all earnings, however small, find their way into banks, or are declared by income payers in the 26AS form. Similarly, as in Hong Kong or Singapore, pre-filled income tax returns will be supplied to other classes of income earners, thereby simplifying their tax filing task. Once again, this could raise questions about possible incomes not reflected in the 26AS form.

Nonetheless, this is a welcome move and one that may gradually generate smoothness of economic activity. In this connection, yet another helpful aspect of the budget this year is that it has not introduced any changes in either the income tax rates or the income slabs. Frequent changes of tax rates or slabs cause uncertainty and, as the Nobel laureate, Robert E. Lucas, pointed out, they often cause economic agents to behave in a manner that runs contrary to the interest of the economy. The demonetization exercise of 2016 was an instance of government-induced uncertainty that ran against the interests of the economy. In fact, the Indian economy’s rate of growth began to fall over successive quarters following that much-criticized policy. Our slowdown, as is well known, began well before the arrival of the pandemic.

Finally, it is best to remember that the budget is a short-term exercise. A single budget will never tell us what is to be expected over the next few years. Unfortunately though, commentators, including economists, often do not appreciate this point.

The author is former Professor of Economics, Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi and Calcutta