|

|

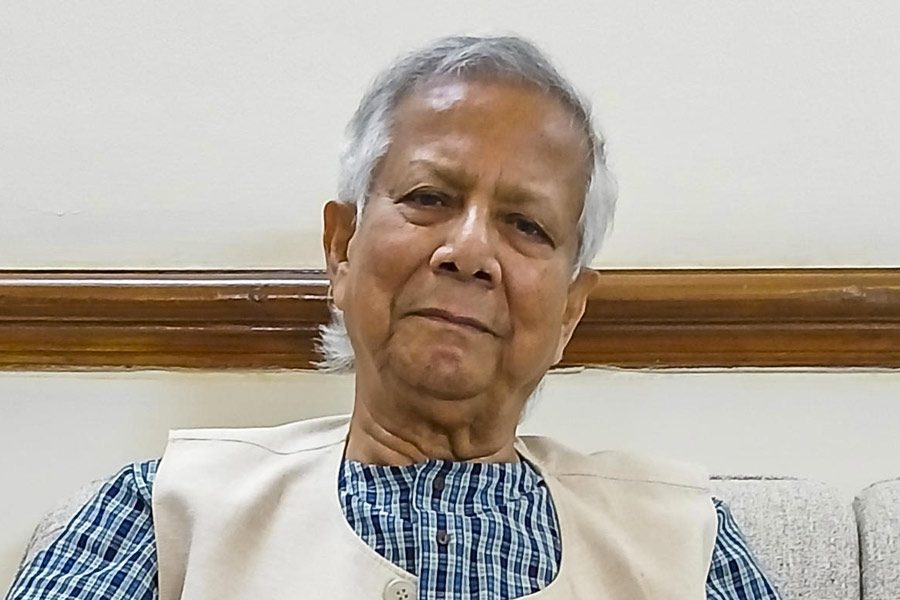

| Anti-bomb protest in Dhaka |

Arguably, Bangladesh might never have exploded in violence if geography had not tucked the world?s third most populous Muslim nation into the folds of Bharat Mata?s sari. History, too, conspires to convince Bangladeshis ? Ziaur Rahman?s coinage to stress they were not Bengalis ? that impoverished boatmen and cultivators who comprise the majority of the 10 per cent Hindus represent a dual threat: as supposed heirs to the lawyers and landowners whose two-hookah culture (a term used by the National Awami Party?s Muzaffar Ahmed) dominated life until 1947 and as Trojan Horse of the nation that overpoweringly surrounds Bangladesh on all sides except where mangrove swamps run into the sea.

No one can predict where the twin burdens of geography and history will take a people whose political sovereignty is stronger than their national identity. Islami Oikya Jote activists, who celebrated George W. Bush?s Operation Enduring Freedom with the chant ?We will be the Taliban, and Bangladesh will be Afghanistan?, have a vision of the future that is certainly not the government?s. It threatens domestic turmoil, causes regional unease, and might attract global attention if the Americans suspect external inspiration. But improbable as it may seem, foreign mischief is less the cause than the effect of a deep-seated sense of insecurity that tinges private conversation and influences public thinking.

Just as the northeastern tribes have seized on Christianity to distance themselves from what they see as India?s Hindu mainstream, Islam is Bangladesh?s greatest psychological prop. As Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto percipiently observed in 1971, a secular ?Muslim Bangla? should merge with West Bengal. That haunting fear, threatening the post-Partition elite?s wealth and power, explained Dhaka?s nervousness when the West Bengal assembly hung Fazlul Huq?s portrait. Visitors from West Bengal are effusively welcomed. But the complex surfaces in snide jokes about Calcutta?s limited shopping facilities, in tacit support for Pakistan and sympathy for Kashmiri separatists. Saudi largesse additionally makes the Organisation of Islamic Conference an important factor in the life of those who must be better Bengalis than the people of West Bengal, claim higher growth than India?s, and affect to see India?s conspiring hand in everything that goes wrong.

The subcontinent lives on memory. No up-country (only that colonial term encompasses the sweep from Calcutta?s Park Circus ? or does it start in Orissa? ? to Pakistan?s North-West Frontier Province) Muslim forgets that the people he considers his progenitors ruled India for 700 years. Few Bengali Muslims forget that only the prefix Syed or claims of Afghan or Arab descent save them from being taken for converts from Hinduism?s lower rungs. Yet, paradoxically, rarely does a Bangladeshi acknowledge that his religion sets him apart from Bengali Hindus. It is almost as if, secretly, he, too, shares the latter?s reservations. I once incurred a minor East Pakistan official?s reproof for saying Calcutta was my home. ?The lotus looks at the sun and forgets the dirty mud from which it rises!? he mocked in English. Then, in Bengali, he drew a distinction between basha and bari. According to him, my basha might be Calcutta but Brahmanbaria was bari. When I repeated the conversation to my mother, she inquired if the man regarded Calcutta as the sun and East Pakistan the dirty mud? He probably did.

Dhaka had hardly any taxis in those days. The only hotel was the Shahbagh which cycle-rickshaws at the airport touted as ?just like the Grand?. Ramna Club regulars plied me with self-conscious questions about the Calcutta Club though theirs was a much older institution. A bunch of young Civil Service of Pakistan entrants took me to task in the Comilla circuit house for what they called West Bengal?s capitulation to Hindi imperialism while they had shed blood for the Bengali language. It was all very friendly, but airport immigration made a point of pushing aside my passport to be checked after everyone else?s, and the police at Lalbagh Fort, where I had to register, were never mindful of the train I had to catch.

One particular conversation on the Green Arrow, the fast train between Dhaka and Chittagong, remains with me. Having discovered I was Indian and a journalist, the two other occupants of the first class carriage, a politician, one of Ayub Khan?s Basic Democrats, and a local official of sorts spent the entire journey pointedly discussing, also in English, India?s Dalits and a certain kind of ape found in Madhya Pradesh that apparently lusts after the female of the human species. They also held forth on Dawn being the subcontinent?s only independent newspaper. East Pakistan was complaining even then of being starved of water. At the same time, it claimed Suchitra Sen and Utpal Dutt as its own.

Abu Zafar Obaidullah, civil servant brother of Holiday?s Enayatullah Khan, insisted that he had given his son, Parthasarathi, a Bengali, not Hindu, name. Many years later when he was Bangladeshi ambassador to the United States of America, Obaidullah sent me his slim book of poems, Prayer for Rains and the Brave of Heart, for review in The Statesman and was disappointed to learn of my severed connection. Of a third brother, Rashed Khan Menon of the Bangladesh Workers Party, Salauddin Quader Chowdhury, now Khaleda Zia?s controversial aide, lamented that he had gone off beef under the influence of Hindu communist friends. Beef, like Islam, has acquired such a defining role that in Dhaka I have to suppress my fear of carelessly cured meat bristling with tapeworm embryo.

Politically, this complex translated ? not in gentle souls like Obaidullah but in robust nationalists ? in affirmations of separateness like Zia?s ?Bangladeshi? and his thwarted wish to replace ?Sonar Bangla? with ?Prothom Bangladesh? as the national anthem. My one formal meeting with him in Banga Bhaban exploded into acrimony because, forgetting that he was a head of state whom I had gone to interview, Zia launched into a diatribe against Calcutta?s ?convent-educated English-speaking? sahibs. Hankering to visit Delhi as president, he insisted on prior guarantees of exactly the same ceremonial honours as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had enjoyed. Only India?s accolade could legitimize his consecration at home.

Though Indian trained, Hussain Mohammed Ershad was no less sensitive to India and what he called Bangladesh?s ?India lobby?, meaning Hasina Wajed and the Awami League. It was his great pride in 1985 that Rajiv Gandhi had promised ? which external affairs ministry officials later scuttled ? to associate Nepal with India-Bangladesh river-sharing talks. ?I have got from India what the India lobby could not!? he exulted over tea in the cantonment bungalow whose cramped informality felt more secure than Banga Bhaban?s marbled spaces. Apologizing to my wife not to consider him regressive, Ershad, who was personally as free of bigotry as the Zias, explained that since a woman could not lead a Muslim nation in prayer, Mrs Wajed would never form a government. ?He?s never heard of Raziya!? Kamal Hossain muttered when I told him. But the conviction led Ershad into making Islam the state religion, thereby further underlining the difference with India, without understanding the Pandora?s Box he was opening.

This preoccupation with India has taken Bangladesh far into turbulent waters whose dangers Mrs Zia, dallying with borderline forces for political, not ideological, reasons, may not realize. Fazlul Rahman, amir of the Jihad Movement, was a signatory with Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri to the notorious ?Kill Americans Everywhere? document of February 23, 1998, which thrust al Qaida into notoriety. The challenge is not only to Mrs Zia?s authority and national stability, but to India, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and the world. But the ineffective brutality inflicted on Afghanistan and Iraq will again be of no avail until Bangladeshis learn to live with themselves, free of a crippling past. They will only compound their anguish by continuing to react against a history and a geography that is beyond anyone?s ability to change.