|

|

| Destiny?s child |

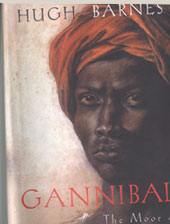

Gannibal: The Moor of Petersburg

By Hugh Barnes,

Profile, £ 16.99

An African boy who was brought to Russia as a slave became Peter the Great?s godson. During the reign of Peter?s successors, he rose to become a general and earned for himself the status of a noble. He was also acknowledged in his time to be the most eminent representative of the Enlightenment in Russia. He was a personal friend of Voltaire and Diderot. He was a polymath and master of many languages and a cryptographer of renown. In his youth, he had been one of Peter?s trusted spies. He was famous as a mathematician and one of the authorities on the science of warfare. This, by any reckoning, is an outstanding curriculum vitae, made even more remarkable by its subject?s origins. To all this should be added the fact that he was the great grandfather of Russia?s greatest poet, Alexander Pushkin.

This man, whose original name is unknown, was known in Russia as Abram Petrovich Gannibal. Hugh Barnes rescues Gannibal from obscurity through some excellent detective work. This is a biography of the highest order despite the absence of the kind of data normally considered to be essential for the reconstruction of a life. Gannibal ? as he was commonly known during his life ? entered history without a birthdate, without a birthplace, and without known parents. He was history?s orphan who Peter adopted. Gannibal later claimed that his father had been an African king but this may have been a concoction to earn himself respectability in a society full of prejudices against blacks and negroes.

Barnes uses the meagre archival documentation that is available. But much has been lost, including a memoir that Gannibal himself wrote and then burnt. Pushkin too narrated the story of his black ancestor in The Negro of Peter the Great which Barnes shows up to be pure fiction. Nabakov too wrote an essay in Encounter on Pushkin and Gannibal. Barnes, through part intelligent use of sources and part imagination, recreates the life and times of Gannibal. He brings to his narrative aspects of travelogue as he takes his readers into Ethiopia to try and find Gannibal?s birthplace; and also on a trek to where Siberia becomes China to locate a fortress that Gannibal built during his Siberian exile.

Barnes is excellent in the recreation of Gannibal?s life and its political context. He provides an account of Peter?s creation of St Petersburg out of marshy land. Peter was a man of indomitable energy, driven by the vision of a Europeanized Russia. His court was a snake-pit of intrigue. Peter was not above intrigue and his violence could be mindless at times. Yet he could be trusting as the life of Gannibal testifies. The latter had to pay the price of being the great Tsar?s favourite. One of Peter?s successors exiled him to Siberia. He made a triumphant return to the court only to be dismissed by a Tsarina. He died on his estate, tending to the garden that he had made.

Gannibal?s was an incredible life. Peter was Russia?s European future, Gannibal, the Byzantine past. Yet it was the African who captured the best of the Enlightenment. If anyone represented Europe in 18th century Russia, Peter?s African slave did. Barnes?s superb biography does not fail to capture the irony. Gannibal would have read Barnes?s work with approval.