|

|

Now that the political storm has passed, it is time to analyse dispassionately how and why the nuclear deal precipitated a crisis that threatened to topple the government. Never before in the history of independent India has a foreign-policy issue led to such a crisis. Even the military debacle of 1962 and the failure of our China policy provoked only a demand for the resignation of the defence minister. India’s foreign policy has traditionally been based on a national consensus defined not as unanimity but as broad agreement between the government and the principal opposition parties. Was this rule breached in the case of the nuclear deal?

The answer is both Yes and No. In a narrow sense, the answer is in the affirmative. The principal opposition party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, adopted the stance that while it was generally in favour of a nuclear deal, it had reservations concerning certain terms of the agreement that called for a renegotiation. It dismissed the assessment of Brajesh Mishra, arguably the leading architect of the Vajpayee government’s foreign policy, that the agreement set out the best terms that could be obtained. The BJP had a legitimate grievance over the failure of the government to hold meaningful prior consultations with its leaders and to share with them the credit for the initiative.

Government spokespersons should have emphasized, from the outset, that the new initiative was a continuation and logical extension of the policy followed by the previous BJP-led government — just as Vajpayee shared with the Congress leaders the credit for the nuclear tests. The government must be faulted for this procedural lapse, but the BJP leaders cannot be excused for failing to subordinate petty personal and party considerations to what they must have known to be the national interest. They knew full well that opening up the agreement for renegotiation would only lead to counter-demands and not better terms.

Despite its posturing, the BJP did not move a no-confidence motion to derail the agreement. The crisis was precipitated by a party that claimed to ‘support’ the government and which derived much of its influence at the Centre from its links with the ruling coalition. In a move that simultaneously undermined the stability of the government as well as its own influence, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) withdrew ‘support’ for the government and joined forces with the Opposition. It was the act of a political suicide-bomber. Driven by a deep ideological aversion to closer ties between India and the United States of America, the CPI(M) general secretary, Prakash Karat, made a desperate attempt to block the nuclear deal, even at the cost of undermining his party’s prospects.

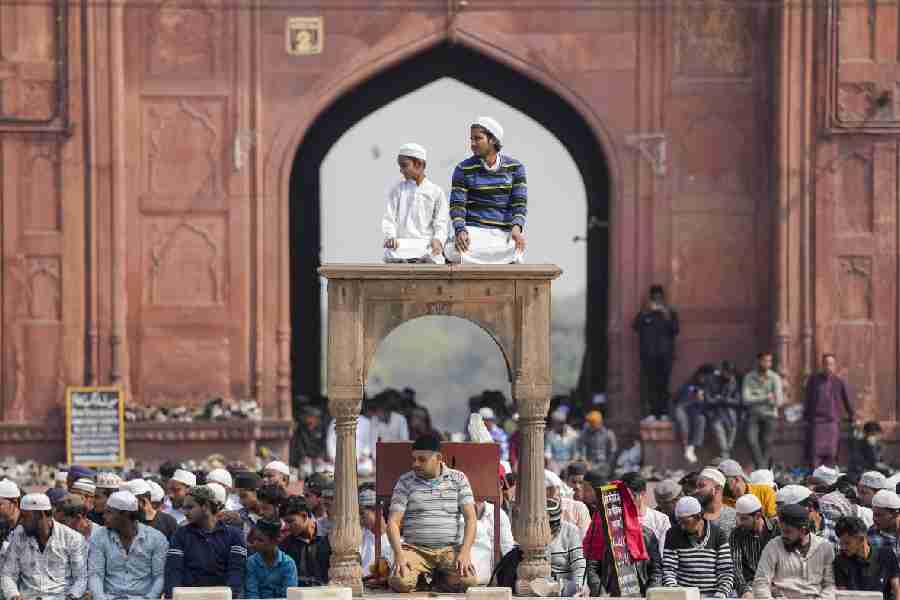

To most Indians, the CPI(M)’s appeal rests mainly on two pillars — its deep commitment to secularism and its solid achievements in the state of West Bengal. Karat’s strategy on the nuclear deal weakened both pillars. Despite protestations to the contrary, it was clear that the CPI(M) had joined forces with the BJP, a party it denounces as communal, against the government. Moreover, the nation was treated to an extraordinary spectacle when the general secretary appeared on a common platform with Shia divines in Lucknow, exhorting the Muslim community to oppose the nuclear deal on religious grounds. (In sharp contrast to Karat, Muslim political and religious leaders have emphasized that the nuclear deal is not a religious issue and that it should be evaluated in the light of India’s national interests.)

A close working relationship with the United Progressive Alliance government at the Centre helped the CPI(M)-led government in West Bengal to implement its development programmes in the state. The party dealt a severe blow to that relationship when it withdrew support for the Central government. Compounding the folly, the CPI(M) leadership committed an appalling breach of constitutional propriety by presuming to order Somnath Chatterjee, the speaker of the Lok Sabha, to step down from his high post. In keeping with his non-partisan role, the speaker rightly rejected his party’s instructions. This sorry episode raises a new and disturbing question. Should a CPI(M) member be considered, in future, for election as speaker — or, indeed, for any other post which requires the holder to act in an impartial, non-partisan manner, in view of the party leadership’s assertion of a right to issue directives to any member?

This question did not arise during the election of the present speaker since no one imagined, least of all the speaker-elect, that CPI(M) leaders would arrogate to themselves a ‘right’ in violation of constitutional propriety. Indeed, the party needs to explain to the Indian public whether it also claims a right to issue directives to its members to violate other canons of propriety. For example, can it instruct party members in the medical profession to violate the Hippocratic oath, or its members in the legal profession to act in breach of the rules of confidentiality? Or is the CPI(M) leadership prepared to rectify a mistake and admit that it acted in haste in a moment of panic without fully considering the legal and constitutional implications of its actions?

Regional parties held the balance in the vote of confidence. Since these parties tend to focus on caste and other sectional interests in a provincial or regional context, they do not usually play an active role in foreign-policy debates. The only significant exceptions to this rule relate to our immediate neighbourhood. For instance, regional parties in Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Kashmir take an active interest in our policies concerning Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan, respectively. One might conjecture that a political figure like H.D. Deve Gowda must have acquired a basic knowledge of foreign affairs in his waking hours during his spell as prime minister, but it is difficult to find supporting empirical evidence. Like other regional politicians, the former prime minister had no views on the nuclear deal till the last minute.

In the event, the UPA and the National Democratic Alliance locked horns in a fierce contest for the transient loyalties of regional parties. Lacking a national perspective on foreign policy, these parties aligned themselves with the government or the Opposition in the context of their domestic — mainly regional — concerns.

We must draw the relevant lessons from the imbroglio over the nuclear deal. First, the consultative process involving the government and the opposition must be invigorated. In particular, the two major political parties at the Centre owe it to the country to overcome bruised egos and personal friction in order to restore a bipartisan approach in foreign policy. Second, regional parties need to take greater interest in international affairs. In an increasingly integrated global system, economic, political and military developments in other countries have a greater impact on our own fortunes than in an earlier age. No state or region is immune to these impacts. Regional parties must develop an educated appreciation of foreign affairs, particularly at a time when they wield increasing influence at the Centre. The debate on foreign policy is currently conducted almost exclusively in New Delhi. This must change; a countrywide dialogue is needed. We require many more foreign-policy think-tanks and discussion fora in major state capitals.

Finally, the CPI(M) leaders owe it to the public to review their decision to issue a directive to the speaker of the Lok Sabha. Somnath Chatterjee has suggested that, in view of the party’s contentious position, a “convention should start now that during his/her tenure as Speaker, a Member should temporarily resign from the membership of the Party and not face a situation which compromises the position of the Speaker vis-à-vis his or her Party”. I am second to none in my admiration for this great parliamentarian, but I respectfully suggest that a more appropriate solution would be for the CPI(M) leadership to review its improper decision and acknowledge its mistake.