|

Jottings: Works by Ganesh Pyne, being displayed at CIMA Gallery till November 22, offers viewers the key to the secret world of the imaginings — often dark, tortured, wild and turbulent — of this reclusive artist who died last year. Pyne’s published writings, though few and far between, offered occasional glimpses of this world where he would dredge up images that haunted him from childhood.

From early in his life, Pyne had an eye for such archetypal images in his immediate surroundings, as the giant statue of Garuda made of cement in a neighbour’ s mansion, the visage of Durga obscured by a veil of fragrant smoke of burning incense, and the terrifying picture of a huge blue face, its eyeballs bulging out and open mouth like a giant cave. Tongues of flame emerged from this opening as it regurgitated and swallowed innumerable warriors on chariots. Later he found out that it was a representation of Arjun’s vishwarup darshan — when Krishna revealed his “universal” or “omni” form at the battlefield of Kurukshetra. Although it did not make much sense to him then, the picture cast its spell on him. This envisaged his fascination with the moral ambivalence in the universe of the Mahabharat, which he visualized in a series of drawings towards the end of his life. Some of these are on display here for he had made the preliminary sketches of these works in his graph paper notebook.

Pyne went on to write that in his early childhood he would scrub his writing slate till it was squeaky clean so that he could scribble afresh on its virgin surface everyday. His grandmother, who was an excellent raconteur, would tell him stories from the Ramayan and the Mahabharat, fairy and folk tales in the evenings, and these would come alive before his eyes like moving pictures — perhaps like pictures projected by a magic lantern.

As the stories unfolded, he would try to capture these moving pictures with the jottings of his untrained hands within the confines of the quadrangle. That is how the artist stole the keys to a fantasy world from his grandmother. His words are a throwback to Ingmar Bergman’s: “When a film is not a document, it is a dream... At the editing table, when I run the strip of film through, frame by frame, I still feel that dizzy sense of magic of my childhood.”

As an adult, Pyne used sheets of graph paper to note down the fleeting pictures and thoughts that crossed his mind, often throwing light on the wellspring of his creativity. Quoting Jung, Pyne wrote: “Life has always seemed to me like a plant that lives on its rhizome. Its true life is invisible, hidden in the rhizome...” According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a rhizome is “a thick plant stem that grows underground and has shoots and roots growing from it”.

This accent on inner life is reiterated in Pyne’s essay in which he reproduced a comment by poet Shakti Chattopadhyay, whose verse the artist famously transformed into visual imagery. The poet wrote after he was shown some of Pyne’s paintings: “This is the intricate poetry of the ceaseless experiences of one who lives in an inner world without limit.” The intricate poetry of pictures, Pyne added, still spurred him to paint.

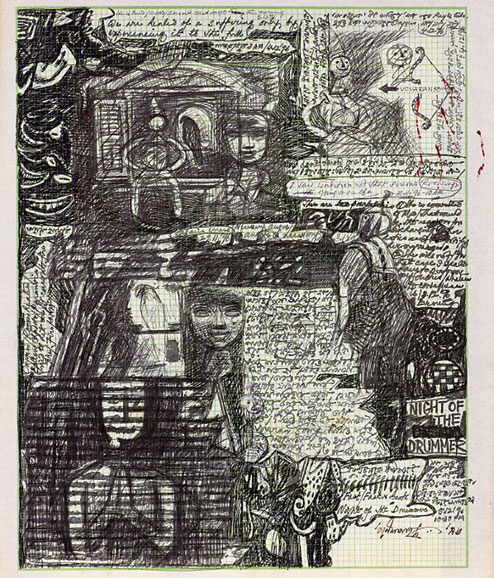

Although Pyne had started scribbling on graph paper long before Neil Gaiman was heard of, the format of these jottings — sketches along with text written in his beautiful, flowing hand, initially in Bengali and later in English — reminds one of graphic novels. They also remind one of the film scripts of many noted auteurs who juxtapose their sketches of shots with text. So when the pages are seen sequentially, a narrative often emerges. This narrative element is strongest in Pyne’s sketches for Sripantha’s book, Metiaburujer Nawab, on Wajid Ali Shah’ s last days, and his Mahabharat pictures.

The resemblance with graphic novels is strongest in a page touched with sepia where a rag doll clown sits on a window sill along with the huge head of another doll whose eyes seem to have been plucked out by a thoughtless child — cruel as only children can be. In between hangs a perch with a cockatoo sitting on it — the kind made with sola pith for decorating rasmelas. Beneath it is a complex image of interlocked sculpted forms that could only have been inspired by those carvings of pre-Columbian serpents.

In another page, Pyne at times scored the text out as mysterious faces and the rag doll clown emerged from the page in a fascinating web of dreams and poetry embedded in each other. Pyne, who early in his career did a stint as a cartoonist, could have been creating a storyboard anew. Like a magician, he conjured up images and half-thoughts, which found their way to his jottings.