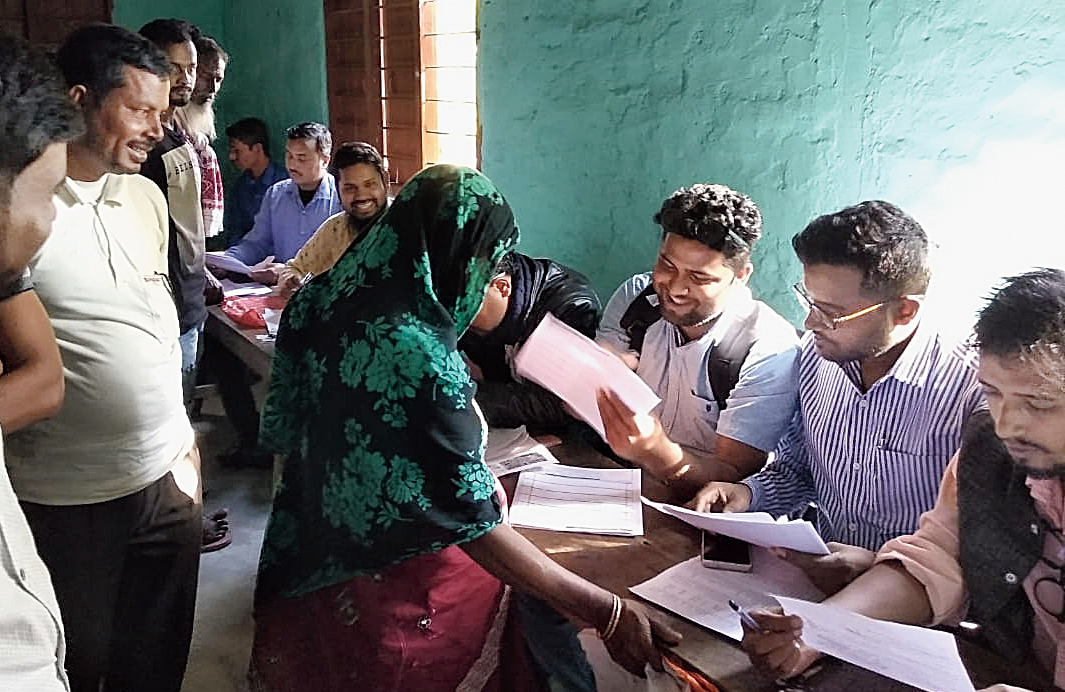

With four million people excluded from the final draft of the National Register of Citizens, Assam is looking at a huge problem of Statelessness, much bigger than the one reported from Myanmar’s Rakhine province. That only less than half a million of the excluded people have filed claims for inclusion thus far compounds the problem, suggesting the bulk of those excluded may not be in a position to provide fresh evidence to secure Indian citizenship.

Nearly 20 suicides have been reported so far from Assam after the NRC draft was published. That those hanging themselves to death were Bengali Hindus or Muslims who have lived in Assam for decades points to the humanitarian dimension of the emerging crisis that was extensively discussed in an international conference organized by the Calcutta Research Group in Calcutta recently.

More than 90 per cent of the excluded are Hindus or Muslims of East-Bengali origin. Those who committed suicide did so to avoid humiliation; else, they were apprehensive of the future.

With the Narendra Modi government having assured Bangladesh that the NRC updating was an internal exercise and no one will be deported from Assam to the neighbouring country, those excluded from the NRC fear that they will spend the rest of their lives in a detention camp in Assam. If the number of those excluded from the NRC stays in the vicinity of two to three million or more, detention camps will be clearly inadequate to accommodate them. Even some hardline Assamese wanting summary expulsions of illegal migrants have now suggested that those dropped from the NRC should be denied voting rights but they should be provided work permits to be able to stay and work in Assam. This is not a manifestation of humanitarian considerations but a desire to secure cheap labour, a recurring challenge for Assam’s economy that encouraged migration from East Bengal in the first place.

But will those excluded be able to retain their land and property acquired through unrelenting hard work? Does it befit the world’s most populous democracy to deny political and property rights to migrants who, after exclusion from the NRC, may be allowed to stay and work with permits? The post-NRC situation is replete with uncertainty over these questions. There are many more that remain unanswered by the authorities in the state and at the Centre.

What is further complicating the crisis is the spiralling demand for replicating the NRC in other Indian states, in the Northeast and beyond, by the Bharatiya Janata Party as well as by regional outfits with stated anti-immigrant postures.

The Supreme Court, which oversees the exercise in Assam, has sought the Centre’s view on whether the NRC can be implemented in Tripura. The state’s BJP government is not that keen, although some tribal parties aligned to the BJP are supporting the demand vociferously. Tripura’s royal scion has moved the court for NRC in the state.

The BJP, however, wants the NRC in West Bengal and in some other states. It had expected that most of the excluded in Assam would be Muslims but that has not been the case. Similar numbers of Bengali Hindus and Muslims have been excluded. The BJP, anxious to manage the Bengali Hindu vote in Assam and West Bengal, had promised to pass the citizenship amendment bill to ensure Hindus excluded from the NRC would still retain their citizenship. But the bill has run into huge resistance in Assam where regional groups and even the Asom Gana Parishad, the BJP’s ally, have stoutly opposed the proposed legislation. The Congress has opposed the bill on grounds that citizenship cannot be decided by one’s religion. In fact, the Assamese regional groups, which had exuded a sense of triumph over the NRC exclusions, are now furious over the citizenship amendment bill because they see their gains from the NRC being eroded.

Ethnicity, not religion, constitutes the faultline in Assam. In its quest of Hindu consolidation that worked during the 2016 assembly elections, the BJP overlooked these ethnic faultlines while attempting to push through the citizenship amendment bill.

The uproar against the bill has led to competitive radicalism with regional groups trying to outdo one another in agitating against it. Senior Assam police officials have suggested that tempers against the bill run so high that large numbers of angry young Assamese have joined the Ulfa, giving it a fresh lease of life. Bengali Hindu leaders sympathetic to the saffron party have exacerbated the tension with their shrill rhetoric, with one of them even threatening the balkanization of Assam through the creation of a Bengali state in the Barak Valley and separate states for Bodo, Dimasa and Karbi tribes.

Assam is pivotal to the Northeast. It is crucial to its future economic growth and to the success of India’s Act East policy. But it is sliding into a dangerous quagmire. Unless that is arrested, India may have to pay dearly.