I have a clear memory of an incident from when I was about five or six. It was the peak of summer in Lake Gardens, the mud of the unpaved roads was rock hard, and the smell from the open gutters was overpowering. I was looking out from my balcony when another kid in a building across Bangur Park leaned out from his third floor balcony and dropped something towards the ground. The thing fell and then there was a loud cry of pain. Then there was a rickshawalla holding his head, looking up at the building and screaming. He had parked under a tree just below the kid's balcony. The kid had dropped a broken half-brick through the tree, maybe just for fun, maybe because he wanted to move the riksha from under 'his' tree, but the brick had found the rickshawalla's head. I could see the man holding his gamchha to his head and what looked to me like lots of dark sweat was pouring down over his white ganjee. Later, someone explained to me that this was, in fact, blood.

There was a hue and cry. People gathered out of nowhere, filling that empty afternoon with their chatter. The boy in the balcony was now flanked by two women, his mother and someone else, and the mother was having a shouting match with men standing next to the bloodied rickshawalla who was now crouched to the ground. The exchange must have been in Hindi, because I hardly spoke Bangla then and I understood everything being said: your kid threw a brick; no, he didn't; yes he did, we saw him; so what? it was an accident; no, he deliberately threw a brick from all the way up there; so what, why was this man under our tree; is this your tree? it's not, it's a tree on the side of the road; so what? so he's a bit hurt, that happens; what do you mean, that happens? look how much he's bleeding; what do you want me to do, take him to hospital myself?; he'll need to go to hospital, we will take him, give us some money. After some negotiation, a servant came down with some money and the procession left for the hospital, someone pulling the injured man's ricksha. Later, I heard that the woman had initially tried to give a paltry two rupees but had had to fork out a full five rupees. Later, the gossip made the rounds among all the servants and local working-class regulars like the jamadars and malis: the rickshawalla had died, no he'd survived but could no longer ply the rickshaw, no he was fine but was planning to come and kidnap the kid and hold him for ransom, no, no ransom, he was planning to snatch the kid and the mother and kill them. Obviously, there is no mitigation for such awful behaviour, but whatever the rights and wrongs of it, I still associate the whole thing with the spearing summer heat.

Each city I knew then had its own kind of heat. The heat in Ahmedabad came without much sweat, and in my grandfather's bungalow it was accompanied by the smell of wet khus in the afternoons, as the mali came around every now and then to hose down the chiks. The heat in Bombay was like in Calcutta, except many more people had air-conditioning, and you could never fully wash off your bath soap with that awful, slimy water, so all day long you thought you were sweating soap. On the rare visits to Delhi, only a brief one in the full blast of May, the punching of the loo stayed inscribed deep in the psyche. At home in Calcutta, the summer went through many avatars across my growing up. There was dry heat, more often there was wet heat, there was post-Kaalboishaakhi heat and, after 1971 or thereabouts, there was lights-gone, fans-not-working, mosquitoes-ruling, load-shedding heat. Growing up and moving away somewhat from the middle-class cocoon, you realized there was also the heat people faced, sleeping on the street or in little kothis, the heat of the jam-packed rush-hour bus, the searing, take-everything-and-turn-it-into-ash heat of the village in Birbhum or Bankura. Just as life gains significance by the fact of death, the summer, or rather the different gears of summer from March to June, was the interminable dead time that injected full, precious meaning to all the other seasons; you learned to give worshipful thanks to the first drops of proper monsoon rain, and you learned to appreciate and savour the post-monsoon semi-heat that lead eventually to the unbelievable, all-too-brief pleasure of what we used to call 'winter'.

Different people will have different memories of this, of course, different takes, and then there will be the empiricist-statisticians, who will unfurl silken swirls of figures in an attempt to strip naked the fallacies of human perception, but something has fundamentally changed about the heat in Calcutta over the past 25 years. They don't make summers like they used to, nor winters, nor even the monsoons.

Since over a hundred years ago, people have been predicting this burgh's demise through civil war and public strife. Back in the day, in the 60s and 70s, the foreign experts used to talk about the "population bomb" and about how Calcutta would go down in an explosive fission of overpopulation. Concurrent was the theory that any worldwide nuclear conflagration would implode the city, merely as collateral damage, with the added indignity that no one had even bothered to bomb it. Now, people casually list Calcutta as one of the first future victims of environmental disasters such as rising sea-levels. Even as a full, easy breath seems more and more difficult to find in this city, people are delivering increasingly brutal scenarios for our demise in the near future. Whether they are right or wrong only time will tell - we've seen off the Cold War and we've passed the population-bomb ball simultaneously to Bombay and Delhi - but what we do need to confront is the hell we are creating for ourselves, without any help or hindrance from the outside.

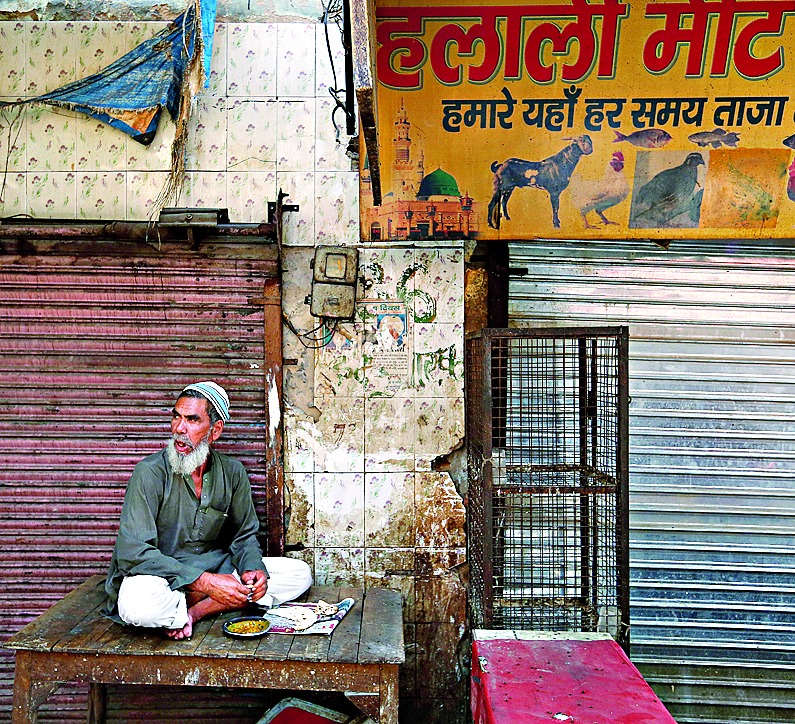

Our weather is going haywire not just because of global phenomena like El Nino and melting ice-caps. It is an inescapable fact that this city cannot support so much built-up concrete, so many air-conditioners, so many cars and other vehicles. The crazy building 'boom' in multi-storeys needed to have stopped years ago, and certainly once the corrupt Left Front lost power. And the last thing we, or the country at large, needed was a soapbox factory churning out cheap, polluting, unsafe toy cars. In any case, the flow of additional new cars into Calcutta needs to be stopped on an emergency basis, even as congestion taxes need to be levied. But neither we-the-feeble nor the Poriborton Merchants have lifted a finger to try and change things. While cities that we claim to admire, such as London and Amsterdam, are adding bicycle lanes and cutting down the areas where private vehicles can run, the same lunatic 'No Bikes' policy of the last days of the CPM is now proliferating across the city. If someone had written a sci-fi novel about Calcutta ten years ago, saying taxi drivers were speeding away from customers at peak hours, and then dropping dead in the afternoon heat, we would have laughed at them for being alarmist fantasists. Look at us now.

Dealing with the extreme vagaries of this summer, it almost feels as if it's the accumulating bad faith of our politicians (and our timid, uncritical support of them), that has led to the weather dealing with us in bad faith in return. As I watch the city stagger under this unnatural heat, I find myself thinking we've dropped many bricks on the weather's head and now the weather's coming to get us.