|

|

Now that Osama bin Laden has been killed by an elite special operation force group belonging to the United States navy, this dramatic operation has answered an important question. Where was bin Laden hiding? It was believed for a long time that he was hiding in Afghanistan or in the border region where both geography and a fierce sense of tribal independence made it difficult to locate him. Pakistan’s establishment repeatedly assured the Americans that he was not in Pakistan. Indeed, it is reported that during a Congressional visit to Islamabad in September 2009, Rehman Malik, Pakistan’s interior minister, had speculated that he might have gone to Iran or Saudi Arabia or even Yemen. Malik went so far as to suggest that bin Laden might be already dead. That he was hiding in the heart of Pakistan in the cantonment town of Abbottabad, near Islamabad, and in a mansion that was practically within walking distance of the prestigious military academy of Pakistan, defies imagination. The mansion in which he was hiding offered comfort and, what is more, security. Built in 2005, the mansion has, as we learn, high security arrangements. The compound of the mansion has high outer walls topped with barbed wire and also internal walls that partition different parts of the compound. Two security gates restrict access.

This operation also raises many questions. How could Pakistan’s establishment claim that it had no clue as to where bin Laden was hiding? The other question that is being asked is: how much, if at all, did Pakistan know of the operation? While credit must go to the United States of America for finding bin Laden and carrying out this operation with deadly effectiveness and with no ‘collateral’ damages, it needs to be asked as well: why did it take so long for the US to find him? George W. Bush had said soon after the attack of September 11, 2001 that he wanted bin Laden in the words of a poster of the West, “dead or alive”.

These questions demand answers. It stretches credibility to have to take Pakistan’s assertion of “no clue” seriously when bin Laden seemed to be living, by all appearances, as a guest of honour of Pakistan in a mansion specifically built with his needs in mind. Suggestions have already been made from Pakistan’s side that bin Laden was cunning enough to choose a location where nobody would suspect his presence. This line of reasoning overlooks the fact that the lack of detection in a cantonment town is not so much a function of the cunning of the person hiding as of the failure of routine checks, intentionally or otherwise. Moreover, the argument can be turned around. Could it be that those sheltering bin Laden chose in a rather daring manner a location that nobody could have suspected as a hiding place for him? Could it be that this location was chosen because bin Laden needed constant medical support? To address the second question now about whether Pakistan knew of the operation, evidence so far seems to be mixed. President Barack Obama’s address itself creates doubts. While he noted cooperation with Pakistan against terrorism, he mentioned also that he called President Asif Ali Zardari after the operation was over to convey what had happened. All the indications coming from Washington suggest that it was treated as a top-secret operation and only a small group around Obama knew about it. A possibility is that, while Pakistani support was taken in minor matters for the ground operation, the overall plan was not shared. Pakistan’s statements on this issue, independent of whether they assert involvement or the lack of it, need not be taken on their face value.

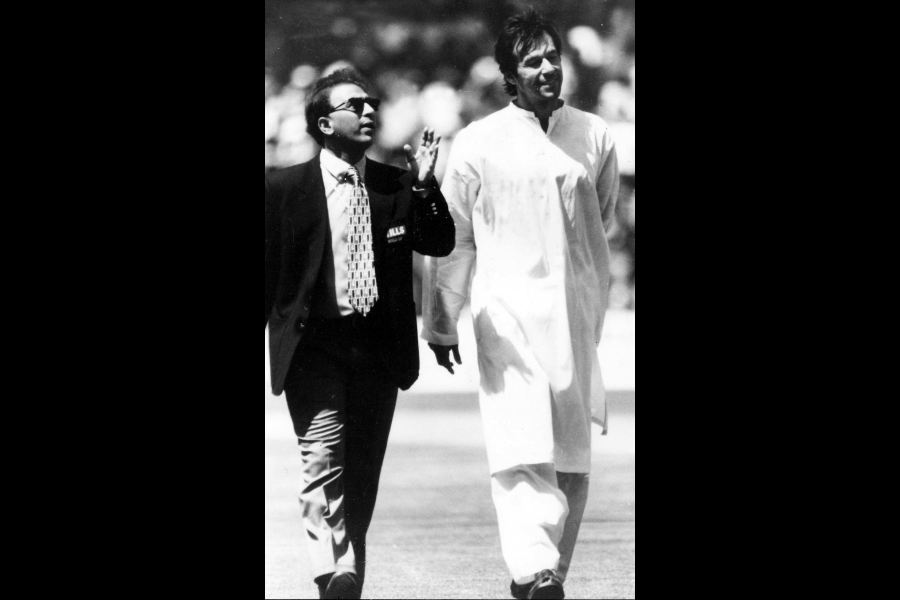

Returning to the last question now, a suggestion may be made that it took the US so long to find bin Laden because the allies against terrorism were also playing the role of protectors of top terrorists. Soon after Obama was sworn in as president of the US, a perceptive American diplomat said something to me that I recalled the moment I heard of the killing of bin Laden. “Bush is a typical man from the American West,” I was told, “for him white is white and black is black. There is no place for grey. If he looks upon someone as a friend, he is a friend and is to be trusted. Obama is more sophisticated.” I was further told that Bush trusted the former president of Pakistan, Pervez Musharraf, fully. He did not see his duplicity. Could it be that Obama succeeded while Bush did not because the former is more competent in handling duplicity?

An objection may be raised here. Is it enough to refer to an American diplomat to describe Musharraf’s conduct as deceitful? It is useful to recall here that his double-dealing regarding Kargil was exposed by Nawaz Sharif himself, Pakistan’s prime minister at the time, under whom Musharraf acted as the chief of army staff. Moreover, as Touqir Hussain, the noted former diplomat of Pakistan, says in the special report to the United States Institute of Peace, US-Pakistan Engagement: The War on Terrorism And Beyond (2005), Musharraf left jihadi outfits unscathed and also did not go against the Taliban with full force to gain by way of leverage in dealings with both India and Afghanistan. Can it not be said with respect to the US as well? Indeed, by all accounts, Pakistan under Musharraf seems to have mastered the dangerous game of duplicity.

There were internal compulsions for this game. The turmoil of Pakistan is to a large extent the creation of the armed forces. They have used all means to cripple the growth of proper democracy in Pakistan as against a puppet democracy and to promote their dominance in all spheres. In this process, space has been created for Islamists. It is useful to read Hussain again: “The country has serious problems relating to social change, governance, and democratization. One can debate endlessly as to whether the army or politicians are to blame for Pakistan’s problems. Seen from a historical perspective, both have failed. Each has done enough damage to fully account for Pakistan’s troubled history. They have both been united in common pursuit of strengthening their class and institutional interests. Indeed, their identities fluctuate and often merge imperceptibly. The army relied on the politicians for its legitimacy, while, in turn, the politicians have relied on the army’s support to keep themselves in power and shield themselves from accountability. Both have pandered to the Islamists, who have provided the ideological underpinnings of a security-denominated nationalism in Pakistan that has guaranteed the military’s dominant political profile. As a result, by creating political space for the Islamists, the military has helped foster religious extremism in the country.”

The American journey in the handling of Pakistan seems to have moved from the time of Bush to the present time under Obama from trust to what may be described here as distrustful trust. This means handling duplicity in an expedient manner. This also means handling internal contradictions within Pakistan’s establishment effectively. To progress further, the Obama administration needs to cross other obstacles as well. Pakistan, yet again under Musharraf, perfected the refrain that could be heard in different arguments presented by it to the US. It went somewhat along the following line: we may be bad but we are trying to reform; break us not, for you may not like us but surely you do not want those who are worse than us to take over from us. The nuclear angle made it more compelling. The amount of money that was extracted under several heads on this ground over the last decade is amazing and needs to be looked into closely.

There is no clear sign yet of a full strategy being in place for handling this threat, but the progress is unmistakable. If the US under Obama could slay a lion (for that is what the name Osama means), is it too much to expect that it will find ways to fight other obstacles as well? Pakistan’s establishment must be made to commit itself against all kinds of terrorism without deceitful deviations. A clear policy needs to address what is suitable for specific objectives not only on practical grounds but also on moral grounds. Indeed, policy objectives themselves require to be redefined in a fast-changing scenario. Recent popular protests against authoritarian regimes in the Arab world open many possibilities. It needs to be appreciated in the US as well as in India and other counties that a democratic Pakistan that addresses the aspirations of its people in a constructive manner is important for this region and also for world peace.