It could have been the Lotos-eaters’ land of Tennyson’s poem. There the languid air swoons like a weary dream while travellers long to rest forever after tasting the “enchanted stem”. But the flowers of unearthly shape and hue on the ‘dream island’ to which Professor Shonku flies in his Shankoplane with his unscientifically minded neighbour, Abinashbabu, are more dangerous. They lure the best scientists to the spot with brilliantly coloured dreams — our professor notes in his diary that dreams are usually without colour — and fasten their petals on their heads to suck up their intelligence as food, leaving the scientists as innocent of thought as infants. But although sinister and breathless, the fantastic adventure never lets go of the promise of rescue, because it is Shonku’s diary we are reading after all — with a crucial interpolation by the sceptical Abinashbabu in this case.

Funny how a virus can affect our past as well as our present. The month of May slid past with the birth centenary of Satyajit Ray, and now June is inching away with Hemanta Kumar Mukherjee’s hundredth birthday already gone. Neither of them could be remembered collectively with the joy and gratitude they inspired in people, yet many are fighting the fear, loneliness and depression induced by the pandemic and the resultant isolation by returning repeatedly to their art. Had they been alive, they may have considered that the greatest celebration of all.

Ray’s inspiration for his internationally famed inventor, Trilokeshwar Shonku, with his laboratory in Giridih, his man, Prahlad, his cat, Newton, and his exasperating neighbour, Abinash Majumdar, may have come from Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger and Sukumar Ray’s Heshoram Hushiar, as he said, but the experience the stories provide is unique. They seem to grow in value when read in these difficult times. The combination of Shonku’s scientific mind and his fantastic adventures creates a widening field for the imagination: while the professor seeks a logical explanation for everything he finds, he is also full of wonder at the possibilities of life and the world. His measured, truthful, frequently irascible, often superior and sometimes nonplussed voice makes readers suspend disbelief only too willingly. Creatures from the past, around the cave in Cochabamba in Bolivia, for example, or from unknown corners of the universe — the blood-red fish that blunder into the waters of the earth by mistake is one instance — or the still unknown possibilities of the mind, brought out unforgettably in “Professor Shonku o Khoka”, or in the story of hypnotism by the enigmatic Chee-Ching, do not seem part of tall stories, but of events eminently possible.

When daily living has shrunk to just a struggle to keep a virus at bay it is almost cathartic when, in “Professor Shonku o Golok Rahasya”, Shonku breaks apart in horror a football-sized globe which houses viruses that can depopulate the earth. The imaginative conviction in the Shonku stories opens up horizons of unlived experience, like a promise of brightness waiting to be fulfilled. The diary form has much to do with the impression of credibility. Yet the diary has a mysterious fate, according to the first tale. Found in the middle of a crater made by a meteorite, it is written in ink that changes colour and is bound in unfamiliar material. Shonku is already elsewhere, presumably living in an unknown planet with strange creatures — it is suggested that these huge ant-like beings are so advanced that even Shonku cannot comprehend their superiority — after he lost his way on a trip in outer space. The diary seems to have been eaten up by ants while its contents had just been given for publication. But wherever he may be now, the professor must know how much we need his Miracurall drug to beat the virus, or at least his Batika Indica pill that can keep hunger at bay during lockdown.

Shonku’s adventures are like a holiday in other worlds, yet tethered to ideas of scientific observation, daily logic and known norms of good and bad. But obvious fantasy is not always needed for the holiday feeling — the Forest of Arden in As You Like It or Sherwood Forest in the Robin Hood stories were holiday spaces that hid away the fantasy. In the Feluda stories, Ray introduces real holidays, because Topshe, or Tapesh, can record Pradosh C. Mitter’s detecting triumphs only when he accompanies his older cousin during his school vacations. Their adventures transform the places they visit, whether within Calcutta — the Park Street cemetery, for example — or in Kashmir, Kedar, the Ellora caves, Gangtok or Rajasthan, or in beloved holidaying spots for Calcuttans of old, such as Puri, Darjeeling and Benaras. Film sets and circus tents are as full of mystery as forests and deserts. Feluda, Topshe and the irrepressible Jatayu, Lalmohan Ganguly, often face danger, because there are killers and goons, narrow escapes and nerve-racking climaxes, and terrifying villains like Maganlal Meghraj. But as in any holiday, there is always the implied assurance that Feluda and company, even without Shonku’s Annihillin pistol, will survive victorious — otherwise how would Topshe be telling us the story?

Here too, the imagination takes flight, taking us out of the stifling sameness of months of lockdown. But the direction is different. The places come alive, luminous as though seen on film, and every character, however briefly glimpsed, takes on a vivid roundedness. Instead of being alone, we are suddenly surrounded by people who startle us — the owner of a private zoo of dangerous creatures in Badshahi Angti, which is the first of 17 Feluda novels, while there are 18 Feluda short stories, the scion of a noble family famous as hunter and writer, whose hunting and writing are done by other people in Royal Bengal Rahashya, dodgy astrologers and mediums, false psychiatrists, weak but opportunistic hangers-on, avaricious collectors of anything from manuscripts to gems, gamblers and statue robbers, as well as clever grandfathers, obstinate fathers, prodigal sons and grandsons, gentle-hearted friends and unselfconscious youngsters. They are not ‘types’. Each is distinct, not just in appearance, apparel, manner and speech — there are few women — but also in class and circumstance, in backstories and in reasons for action and inaction.

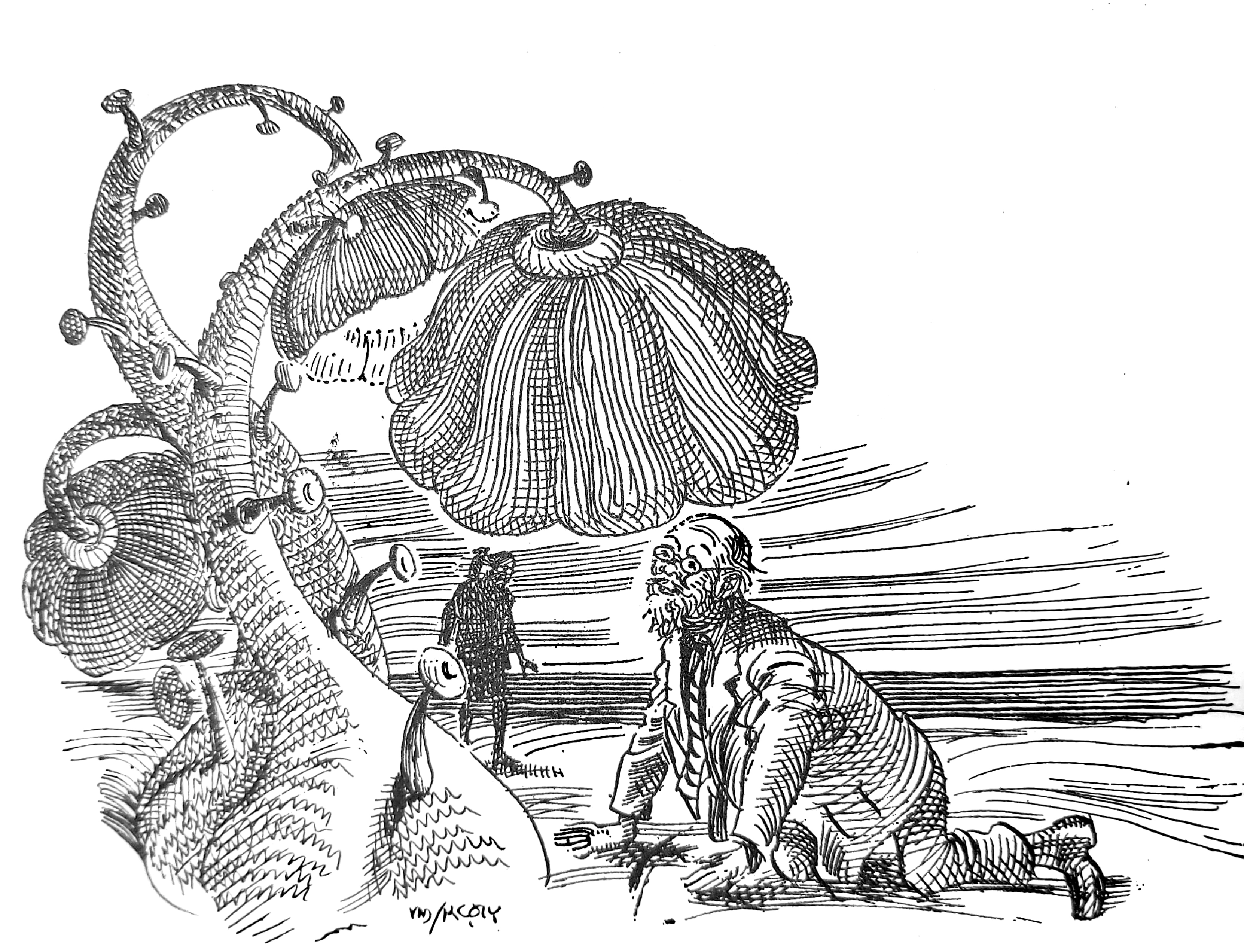

The worlds of Shonku and Feluda share humour, compassion, curiosity, rejection of greed and an unbending, often subterranean, sense of justness. Although many of Ray’s short stories, such as “Ashamanjababur Kukur”, “Brihachchanchu” or “Bonkubabur Bondhu”, have the same qualities, others are irredeemably sinister, such as “Khagam” or “Batikbabu”, or are layered and ambiguous, such as “Sadanander Khude Jagat” (here ants play a crucial role again). They are no more forgettable than the Shonku and Feluda stories — just the illustrations in the oeuvre leave indelible impressions — but the independent short stories offer less of a holiday in spite of the unusual characters that people them. In these Ray frequently focuses on the extraordinary that hides within the most inconspicuous, apparently run-of-the-mill individuals. That is an achievement in itself, but it may not offer quite such friendly an imaginative escape as Shonku’s or Feluda’s adventures.

I have said it: escape. Must fiction that offers the chance to breathe a different air, to feel engaged for a little while, to be delighted and illuminated, to forget — there it is again — the darkness of life and the fear of sickness for the space of just a few pages be considered ‘escapist’, a description negatively loaded? But Ray’s stories are the opposite: they bring greater clarity to the reader’s experience of the world, rich in possibilities, but lucid in logic and a kind of imperturbable sanity.

He is so youthful; how can he be a hundred?