|

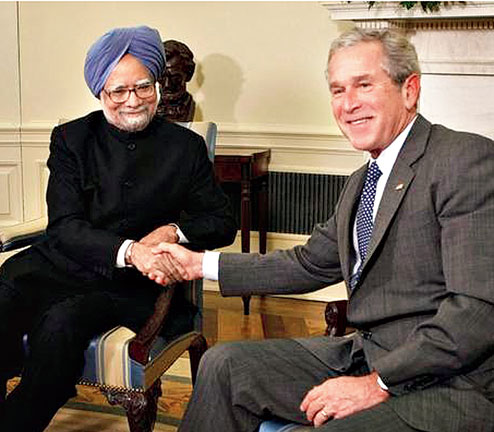

| The US president (right) and the Indian prime minister during the signing of the Indo-US nuclear deal, 2008 |

Indian Foreign policy: A Reader Edited by Kanti P. Bajpai and Harsh V. Pant, Oxford, Rs 1,095

Nothing ages more rapidly on the page than opinions on contemporary international affairs, and this book is a good example of such decadence. Kanti P. Bajpai and Harsh V. Pant, the two pall-bearers in this case, have selected 14 essays under four sections: Ideas, Power and Capacity, Bilateral and Regional Relations, and Global Diplomacy, and since these articles had all been previously published — one as early as 2001 — and are by the ‘usual suspects’, there is little hope of originality. There are no contributions from erstwhile practitioners and there is no authoritative first-hand input. The justification for the book may lie in the sub-title — a reader — which suggests that these re-treads are for those looking for a short-cut to information. The saving grace here is, however, a thought-provoking introduction by the two editors, who despite the obligatory genuflection to Hindu epics, the Vedas, Laws of Manu, Kautilya et al, are nevertheless able to conclude that these hallowed texts have scant traction among those involved in national strategy.

Turning to the main themes in the book, the Ideas section suggests that Nehru’s legacy and non-alignment have lost ground; the discourse is now about domestic issues, economic growth, cultural outreach and military prowess. In power politics, India is a technological laggard with many vulnerabilities and its ability to project and promote its laws and values is limited — though these attributes are neither defined nor elaborated upon. Its software lead is being eroded and China leads massively in hardware. Its population may overtake China’s but the quality of skills is very low. It has not been able to translate soft power into smart power, which combines soft and hard power, and in any event, it is now widely accepted that soft power is least effective when it is sought consciously to be deployed to serve national objectives. In trade, its tariffs are too high and its infrastructure is feeble. Foreign policy software is weak; too small a cadre of diplomats and poor credibility and performance of think tanks, universities, media and private sector in terms of training and research. All this runs counter to great power status. In addition, military power is constrained by the lack of domestic manufacture of any major platform; only nuclear weapons and missiles are locally produced.

Coming to the largest section, which is on bilateral and regional relations, Indo-Pakistan ties are marked by enduring rivalry. India’s relative power is limited by Pakistan’s military capabilities, its offensive strategies and alliance building against India, especially with United States of America and China. With China, India is the status quo partner, with China blowing hot and cold about territorial claims and both countries holding a “strong, even unrelenting, approach to territorial sovereignty”. Both sides have a sense of victimhood from the past, an insistence of entitlement in the future and a quest for status and respect. There is a rising surge of nationalism in both that make concessions difficult. The US is uninterested in India as an alliance partner to contain China, though it has a long term stake in India remaining democratic and independent. To state the obvious, institutional arrangements are only as strong as the states that stand behind them, which is the case in the non-proliferation regime and the Indo-US nuclear deal of 2008; international rules and obligations are always dependent on the interests of the great powers. Indian strategic horizons have advanced not only eastwards, but elsewhere in search of energy and trade. In reflecting Indian concerns on the high seas, the greatly under-resourced Indian navy is in danger of over-extending itself with multiple international commitments.

Turning finally to global diplomacy, India has been consistent and successful in the climate change debate, namely, the responsibility of the West for creating the problem, the common but differentiated responsibilities, and the polluter pays. This means the West must submit to verifiable reductions in emissions and the rich must provide technology and funding for the poor to adapt. But there will be increased pressure on India and China, and not only from the developed countries, to accept verifiable constraints on carbon emissions. India needs a deal, as does China, and is in a weak bargaining position. In global trade, India is a central player and part of a small group within which consensus has to be reached. It has been ready to stand alone and insist on ‘nothing is settled unless everything is settled’. But here again, among developing countries, there is a growing feeling that India, China and Brazil have to be regarded as a special case and dealt with separately. On non-proliferation India may have modified its position on the discriminatory aspect after the Indo-US deal, but in trade it has remained loyal to seeking justice for the developing countries, perhaps with an eye on the advantages of associating in a leadership capacity with a larger group of countries.

There are not a few contestable assertions in this book. The nuclear deal is seen as “one of the most historic strategic decisions of independent India”, equated with another, the Indo-USSR treaty of 1971. The book claims that there has not yet been any assessment of the efficacy of non-alignment, and admits to boundless admiration for the late K. Subrahmanyam. Most students and practitioners of Indian foreign policy would disagree with such conclusions. And who is this book for? It claims as its readership graduate students, those teaching courses in international relations, and the general public. The third category will be beyond reach, but Bajpai and Pant distill the essence of the chapters in their introduction and raise important questions even if they do not — and do not claim to — furnish any answers.