|

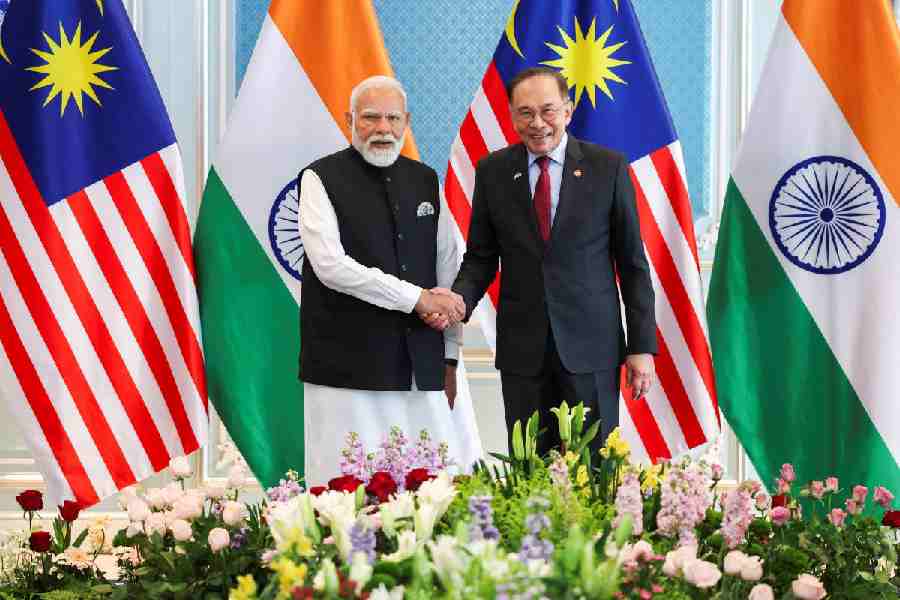

| Emma (Gwyneth Paltrow) and Mr Knightley (Jeremy Northam) at the end of Douglas McGrath’s film, Emma. A different version of the moment is reproduced by Tandon |

Jane Austen’s Emma: An Annotated Edition Edited by Bharat Tandon, Harvard, $35

“Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken” — so chimes in a familiar impish voice at the end of the scene in which the hero and the heroine of Jane Austen’s Emma finally ‘disclose’ their love for each other. Emma and Mr Knightley confess their love, all (or most) misconceptions are cleared away, the ‘villains’ are punished by being paired off with their equals — one would expect a shower of confetti, a rosy glow or chants hymeneal to mark the felicitous occasion. Instead, there is this voice telling the reader that there may be more in the minds of the two than what they are letting out.

It is a dreaded voice since it has the dangerous tendency to laugh in, and at, even the gravest of situations (like this one) and more dangerously, to fall silent at crucial moments. Imagining the tittering accent, the mind automatically goes back to the image of Jane as painted by contemporary gossip. There is the clergyman’s daughter sitting quietly in the corner and observing the world with relentless eyes. As a girl without a fortune, she would have been easily dismissed by genteel society as a fit candidate for acerbic old maidhood had she not begun to write. Mrs Mitford’s lady friend, who visits the Austen household, can express only her grudging admiration for the woman who refuses to fit in. She says, “[Jane] has stiffened into the most perpendicular, precise, taciturn piece of ‘single blessedness’ that ever existed, and… until Pride and Prejudice showed what a precious gem was hidden in that unbending case, she was no more regarded in society than a poker or firescreen.” The gracious lady continues: “The case is very different now. She is still a poker — but a poker of whom everybody is afraid.... A wit, a delineator of character, who does not talk is terrific indeed!”

Critics and Austen addicts have long been trying to read her silences — for instance, on issues of great national significance like the Napoleonic wars happening in the 1810s, during which most of her novels came out. The patronizing tone adopted by Austen’s more famous contemporary Walter Scott in differentiating his own “Big Bow-wow strain” from the homely one of Emma’s author, who “confines herself chiefly to the middling classes of society” must still be rankling with them. Scott’s “young lady” was evidently not into historical novel-writing, having decided early on in life to settle on a “little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory”. But on the farthest rings of the concentric circles that centre on her studies of provincial life are Sir Thomas Bertram’s overseas estates in Antigua (Mansfield Park), or Mrs Elton’s Bristol with its murky implications of the slave trade (Emma). These places, which produced the spoils on which the Empire thrived, constitute the larger world about which Austen is seemingly silent. She certainly does not bow-wow about the darkness out there, but her telling reticence on these issues should be enough to warn the readers of their uncomfortable presence.

Critics have been unearthing such hints ever since Edward Said wrote his essay on Mansfield Park in Culture and Imperialism (1993). Bharat Tandon, the editor of this annotated volume of Emma, pitches in by reading Austen’s comments on social change, social mobility, possible disruptions, and alternative endings in things like a barouche-landau, Stilton cheese, Pembroke table or Broadwood piano. For him, objects like these make up the “The Jane Austen Code” as they gather meaning beyond their thing-ness when seen in relation to the subject. This is undoubtedly an interesting way of placing Austen in context and judging how contemporary social reality impinged on her narrative. Since this is an illustrated edition, here one also gets to see nice pictures of Regency furniture, costumes, of places like Bath or the infamous Box-Hill, and of architecture of the kind that would make up Emma’s Hartfield.

Yet, one may question the premise of an annotated Emma since one of the chief pleasures of reading Austen is that her voice is still fresh, and one need not look up books on Regency manners to get her meaning. Tandon argues his case cogently in the Introduction, pre-empting the reader’s resistance by showing how, in a novel which thrives on “gossip and implication, on hints and innuendoes”, little objects of desire make up a short-hand for other stories lurking on the margins of the narrative. “Austen’s choice of significant narrative details could often say more and other things to the novel’s original readers, in ways that may no longer be so clear — and that was where annotation might be of help... Rather than telling readers how to interpret the novel (which would rob them of the whole fun of reading), I wanted only to shed enough light on Austen’s details to enable individual readers to make their own informed decisions regarding exactly how the details connect with those contexts that time has rendered less manifest.” This is very helpful indeed; the turgidity of Tandon’s prose should not necessarily lead one to think that the editor doth protest too much.

Some of the notes, as those on the possible connections of the outré Mrs Elton with the Bristol slave trade that she is too eager to deny, are enlightening. There are other rewards too. The letter as a document figures prominently in Emma, and Austen has some fun, as usual, with the epistolary form, which was a rage in the 18th and 19th centuries. Frank Churchill equivocates constantly in his letters, and his readers, only too eager to be taken in, find exactly what they want to discover in them. Tandon provides a one-page facsimile of the ‘Mad Papers’ from the third edition of Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa showing “disordered scraps of print [that] are designed to suggest disparate jottings on a sheet of paper, and thereby the disordered state of the heroine’s mind at this stage in the novel.” So, while Austen’s predecessors and contemporaries were trying out various methods to recreate reality in the space of fiction, Austen was busy showing how reality itself is a fiction that we create to suit our purposes.

It often has been said that Austen would have been very amused at the gushing praise and nitpicking analysis all her novels elicit. I think she would have loved this edition since it brings together in snippets all the academic baggage Emma has gathered over the years. Reminding one of the scholarly battle over the precise number of Lady Macbeth’s children, there is Tandon quoting Jill Heydt-Stevenson who found Austen raising the possibility that the “clearly asexual Mr. Woodhouse might have been a libertine in his youth and now suffers from tertiary syphilis.”

In case you did not understand what the adjective, “pretty good”, as applied to “opinion”, signifies, Tandon has a note saying that it means “fairly high”, but the meaning is “ambiguous” — there is a quote from one of Keats’s letters to prove the editor’s point. Then the word, “interesting”, in the sentence “The morning of the interesting day arrived” must be straitjacketed into meaning “important”. With such attempts at explanation — which can have a rather disquieting effect — Tandon unfortunately does succeed in robbing readers of the fun of reading.

This edition is perfect as a gift since Tandon has made Emma into a picture book on the one hand and a text of high academic seriousness on the other. Given its bulk, it can also come in handy as a fair murder weapon. But one should not complain — knowledge has always had its weight.