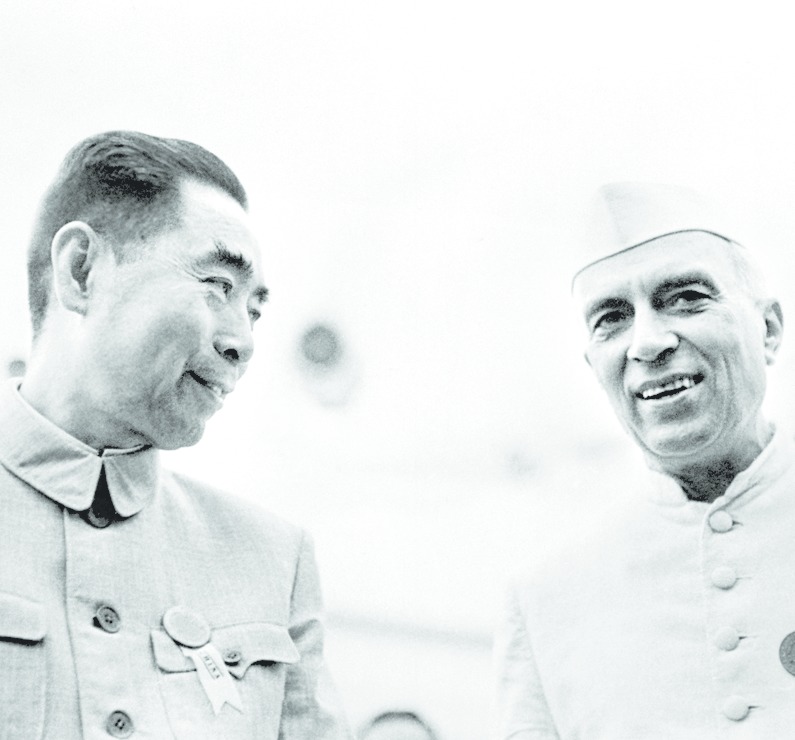

This may come as a surprise to many Indians but Panchsheel, or the Five Principles, was authored by Zhou Enlai, not Jawaharlal Nehru. The Chinese premier proposed the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence for the first time when he received the Indian delegation for the talks on the Tibet agreement on December 31, 1953.

The Chinese premier was not pursuing an abstract philosophical goal. He forged the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence as an instrument to advance specific political objectives. Towards the end of 1953, the Korean war was drawing to a close and global attention was shifting to the struggle in Indochina. The United States of America was taking the initial steps to build an Asian alliance to 'contain' communist China. Beijing's role in Korea and the vivid display of its military power had given rise to serious concern in many Asian countries. In this situation, Beijing required a major image makeover to assuage the apprehensions of its neighbours and to play upon the differences between the US and its European allies - the United Kingdom and France. Declassified Chinese documents reveal that in a meeting with senior Chinese diplomats on June 5, 1953, the Chinese premier, Zhou, explained that the aim of the new strategy was to weaken the ties between the US and the two 'intermediate zones' comprising western Europe and the third world countries, respectively. The strategy was immediately relevant in the context of a peace agreement in Indochina and US moves to build up new military alliances in Asia.

During the Tibet negotiations, both India and China recognized the significance of the Five Principles in the bilateral context as well as the wider context of the Cold War. For China, the latter was more important; India, with the border issue in mind, laid emphasis on the bilateral dimension. Thus, while India wanted the Five Principles to be included as an operative article of the Tibet agreement, China pressed for embodying it in a separate press communiqué. The two sides finally reached a compromise and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence were incorporated in the Tibet agreement in the form of a declaratory statement in the preamble (as distinct from an operative article).

Zhou Enlai lost no time in pursuing his new strategy in the Geneva conference on Indochina. His aim was to obtain a cessation of hostilities in Vietnam, and the neutralization of Laos and Cambodia in order to prevent the US from establishing military bases on China's south-east Asian periphery. After the famous Vietnamese victory at Dien Bien Phu, France was increasingly reluctant to continue the colonial war in spite of US efforts at persuasion. The conference resulted in the Geneva Accords, providing for a cessation of hostilities, the temporary division of Vietnam, and a neutral status for Laos and Cambodia. The signatories to the accords were the Soviet Union, China, France and the UK; the US merely "took note" of the agreements but declined to sign. Mao Zedong explained the Chinese negotiating posture to the politburo as follows: "In Geneva, we have adhered to the slogan of peace, thereby portraying an image of being for peace; whereas the US refuses to adhere to such a slogan and thus forges an image of being for belligerency which makes no sense..."

What did India expect to gain from Panchsheel? Jawaharlal Nehru hoped that Panchsheel would, to some extent, restrain China from launching aggressive actions along the frontier. As he explained in the Lok Sabha: "...in the final analysis, no country can trust another country...therefore it is a question of our following a policy which... makes it more and more difficult progressively for the other country to break the trust. We need not live in a fairy world where nothing wrong happens ... but we can create an environment where it becomes more dangerous for the other party to break away from the pledges given". This is hardly the gullible Nehru caricatured by his critics.

India's advocacy of Panchsheel had a second dimension. In early 1953, Washington announced that it would offer military aid to Pakistan and promote new defence pacts in Asia. The induction of Pakistan into the US military alliance system brought the Cold War to India's doorstep.

The change in US defence policy created a significant degree of convergence in Indian and Chinese interests in south-east Asia. Both favoured neutralization of Laos and Cambodia and saw Panchsheel as an instrument for consolidating the non-aligned 'zone of peace' in Asia. Thus the joint statement issued after Zhou Enlai's visit to India in 1954 declared that Panchsheel will "help in creating an area of peace which, as circumstances permit, can be enlarged".

Nehru was also concerned that even non-aligned stalwarts like Burma (now Myanmar) and Indonesia might weaken in their commitment due to misgivings about China's intentions. He therefore urged Zhou Enlai to assuage these concerns. On his urging, U Nu agreed to issue a joint statement with Zhou affirming that Panchsheel should also guide Sino-Burmese relations.

Panchsheel reached its zenith in the mid-1950s. By the end of the decade, India-China ties were seriously damaged on account of border clashes and unfounded Chinese suspicions of Indian involvement in the Tibet uprising. Panchsheel was dropped from the India-China lexicon. It reappeared only after the thaw achieved during Rajiv Gandhi's visit to Beijing in 1988. Today, its periodic reiteration evokes neither the high expectations nor the passionate opposition of yesteryear.

The alienation of India impaired the efficacy of Panchsheel as a tool of China's Asian policy. However, Beijing displayed remarkable resourcefulness in evoking the Five Principles in very different contexts. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese foreign policy underwent more than one dramatic shift. The Sino-Soviet split was followed in course of time by a rapprochement with the US. Each shift occasioned an invocation of the Five Principles.

At the height of the Sino-Soviet split, in the wake of armed border clashes on the Ussuri river, Zhou Enlai proposed to Alexei Kosygin that bilateral relations might be stabilized on the basis of the Five Principles. Not surprisingly, given China's unpredictable behaviour during the Cultural Revolution, the proposal failed to elicit a positive response.

Zhou Enlai fashioned the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence in 1953 as an instrument to counter US policies in Asia. China had little interest in applying the principles to its relations with Washington. Indeed, at the end of the decade, it actively opposed Moscow's position on peaceful coexistence between the rival blocs, issuing strident calls for world revolution. In a dramatic turnaround, China and the US agreed to normalize their relations in 1972. The decision was set out in the Shanghai Communiqué, which included a paragraph reciting the Five Principles, with a mutual pledge to apply these to Sino-US relations.

Thus, within a space of two decades, the Five Principles completed a full circle. Originally conceived as an instrument for opposing the US, it was re-invented as the foundation stone of Sino-US relations.

China's supple diplomacy illustrates the fact that principles may be immutable, but not their interpretation. States typically reinterpret principles to suit shifts in foreign policy. Public opinion in a democracy needs to be educated to distinguish between dharma, the ethical code that should guide our personal actions, and rajdharma, the compulsions of national interest that must shape the actions of States.

The author is a former ambassador