How is music made and, more interestingly, unmade? How are musical actions, situations and relationships related to other forms of creation and destruction? How does music relate to language and writing, to the meaning, sound and look of words in different languages? In what sense is music material as well as immaterial, disembodied as well as embodied? Where does music reside in relation to the bodies of living creatures like human beings or birds, and to the places (and spaces) they happen to be in? Between the composer and the performer, who can claim greater authorship of the music? Is music as transnational or universal as it is often made out to be? If not, then how do we compose, perform and listen to music politically - that is, as located or migratory agents working within pure and impure, or natural and artificial, histories and traditions?

These are some of the theoretically large, but practically concrete, questions that resonate through the compulsively variegated multi-media work of Samson Young - a composer, performer, writer as well as visual and sound artist, born in 1979 and based in Hong Kong. With a father who came into Hong Kong from China illegally on a boat as a child, Young studied music and philosophy in Australia, composition at Princeton, and has been chosen to represent Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale next year, after a restively itinerant and multilingual career so far. So, a highly self-conscious and verbalized hybridity - at once classical and postcolonial, lyrical and irreverent, intellectually expansive and technologically adventurous - informs his work in all these different capacities, the boundaries among which are wilfully blurred.

It is the blurring of these boundaries - linguistic, generic, material, geographical - that we get to sample through some tantalizingly inadequate glimpses at Young's show at the Experimenter gallery (until October 29) called, with deadpan irony, Mastery of Language Affords Remarkable Power. Inadequate, not because of the quality of the work shown here, which is consistently fine, but because of this exhibition's focus on the visual (and visually pleasing), given the difficult, varied, sophisticated and challenging nature of Young's artistic sensibility and intellect. One misses around these mixed-media works, videos and happenings, beautifully mounted in a gallery, the invigorating and high-precision muddle of a composer and performer's laboratory of natural, composed, notated, gathered and scattered images, sounds and texts that one imagines to be this artisthinker/writer/ musician's natural habitat, based on a cursory acquaintance with just his website. The full import of the show's title, of the fact that five of the eight works shown here are dedicated to Frantz Fanon, and of the subtle layering of word, image, sound and silence in the work, begins to be felt only in the larger context of the extensive range - and political, literary and musicological preoccupations - of Young's corpus of ongoing projects, experiments, compositions, articulations and performances.

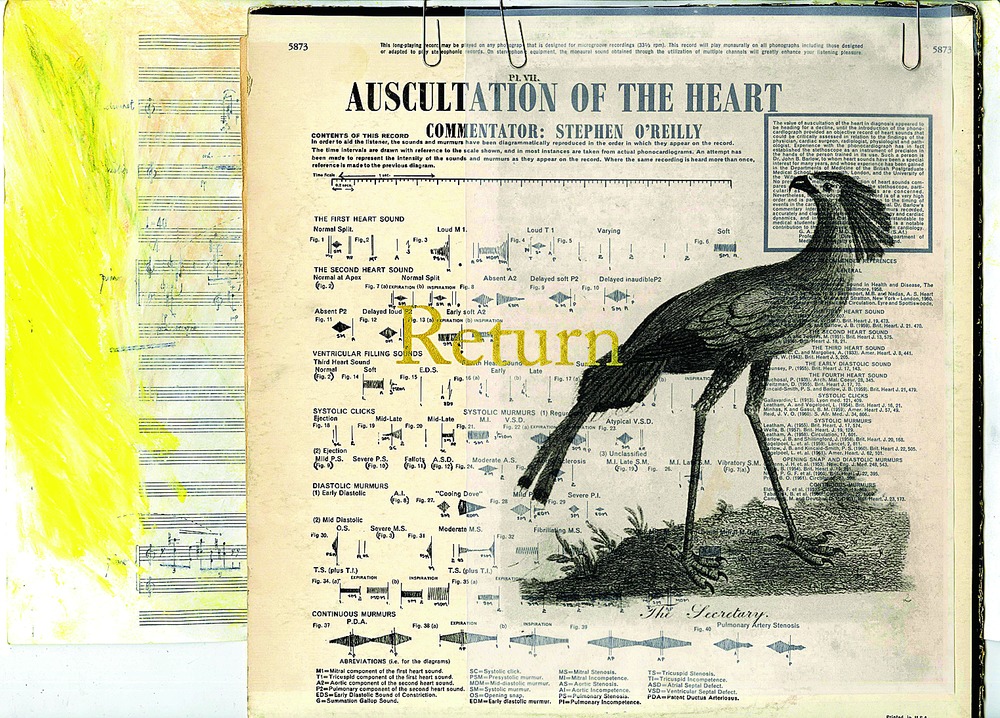

The collage-like sequences dedicated to Fanon recycle and "vandalize" handwritten manuscripts of Young's own musical compositions that have been performed and recorded but not made copies of, so that he would not be able to stage further performances of these compositions in the future. The videos present "muted situations" in one of which a classical string quartet by an un-named European male composer is performed by Chinese musicians, but without the actual notes being sounded, so that we observe and hear everything but the music. The other presents a traditional Chinese lion dance, but again with the "sonic 'foreground'...consciously muted or suppressed", revealing "the less-commonly-noticed" visual and auditory layers of the dance.

The other work "happening" in the gallery while the show is on consists of the gallerists entering into a contract with the artist to learn to sing and play on the banjo Bill and Charles Monroe's 1935 version of "What Would You Give In Exchange Of Your Soul": "The transference of the Artwork in question," says the contract, "shall take the form of the passing of knowledge... through the process of teaching the song... by the Gallerist to another individual."