At the Myanmar media development conference in December last year, journalists and editors had sounded pessimistic about press freedom and censorship. Most of them said the press in Myanmar was still muzzled, and some who had actively supported the movement for democracy and suffered for it blamed the Aung San Suu Kyi-led government for failing to live up to its promises of ensuring freedom of expression. But there was near total consensus that the crisis in Rakhine - after the guerrilla attacks on 30 police stations in August last year by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army - had put the clock back alarmingly on freedom of expression as a whole and media freedom in particular. The all-powerful military had found the crisis rather useful, not only to boost its own image as the protector of national sovereignty but also to reinforce the draconian censorship that had been the overriding feature of 50 years of military rule in Myanmar.

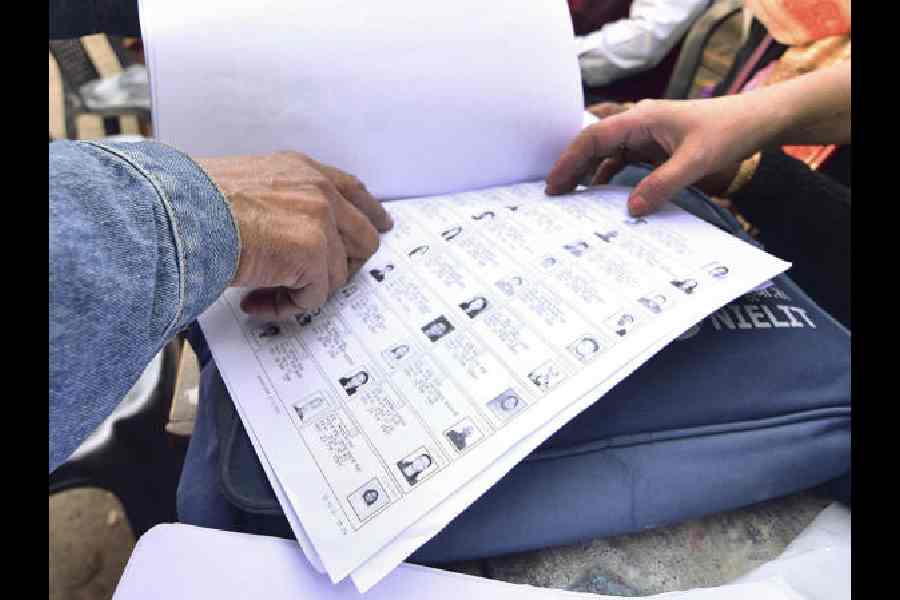

The week after the conference saw the arrest of two Reuters journalists. The government said in a statement that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were arrested for allegedly planning "to send important security documents regarding security forces in Rakhine state to foreign agencies abroad." They are facing up to 14 years in prison under the Official Secrets Act. The journalists' association of Myanmar said the arrests were an "attempt to intimidate journalists who are attempting to do their job of investigating and reporting the news under difficult circumstances." "From our understanding, no detail has been provided about the supposed 'security documents' or the mysterious 'foreign agencies'," said Soe Myint, the chief editor of the Mizzima media group, which has been at the forefront of the fight for media freedom and democracy in Myanmar. To add insult to injury, the authorities provided a photo accompanying the government's statement showing the two journalists standing handcuffed behind a table covered with documents, an image designed to suggest their guilt.

The civilian government led by Aung San Suu Kyi coming to power in 2015 had raised hopes of more respect for media freedom. But the regular arrest of journalists will only damage the government's reputation further at a time when it is already facing severe criticism at home and abroad over its handling of the Rakhine crisis. "We believe that reporters have the right to visit sources of news and also... to collect and question facts relating to such news for the sake of presenting accurate and correct stories," said Sein Win, the training director at the Myanmar Journalism Institute. Thin Thin Aung, who is a co-founder of the Women's League of Burma and one of the Mizzima directors, had raised the question of the Right to Information Act during the conference. During a panel discussion on the subject, she insisted that the government should create a full-fledged national RTI commission, staff it with men and women of stature who are committed to the national democratic process instead of officials and politicians, and weed out any ambiguities in the RTI law to ensure maximum disclosure. Most important, Thin Thin insisted that the bogey of security emerging out of Rakhine crisis should not be used to sweep all information under the carpet.

But the presentation of a senior Rakhine journalist, U Aung Ko, made it clear that proactive disclosure was a far cry in Myanmar and the ground realities, specially in the many conflict zones of the country, were totally different. The authorities have barred or severely restricted reporters from visiting the troubled northern region of Rakhine State, thus making it hard to obtain accurate information. The arrests were seen as an attempt to scare the media. There were at least 17 legal provisions - from communication law to electronic law to the dreaded penal code - under which journalists could be arrested and perhaps jailed for life. Hence the persistent call for a stronger national media law that could override all these legal provisions and help the media report without fear or favour.

"In [the] case [of the arrested Reuters journalists], though we accept some of the facts collected should not be disseminated into the public domain as they might threaten state security, accusing these reporters of violating the Myanmar Official Secrets Act is a threat to the freedom of press, and a misuse of an archaic law enacted in 1923 by British colonial authorities," said the journalists' association's statement. "We are concerned about the alleged denial of access to the detained reporters by family members and worried about the violation of their fundamental rights. We call on the government to explain this incident with full transparency and release these detained reporters as soon as possible."

The government has shown no signs of conceding to such demands. In an earlier debate on film censorship during the Memory film festival last year, Burmese film-makers were joined by many from other south-east Asian countries to demand a new motion picture law which would replace draconian censorship with a 'reasonable classification' system. The old motion picture law is being redrafted amid the debate sparked by the scrapping of a feature film which dealt with the military.

The Rakhine crisis has not only slowed down the march towards democracy in Myanmar but also reinforced some of the oppressive features of the long military rule. Gagging the freedom of expression tops that list.