|

|

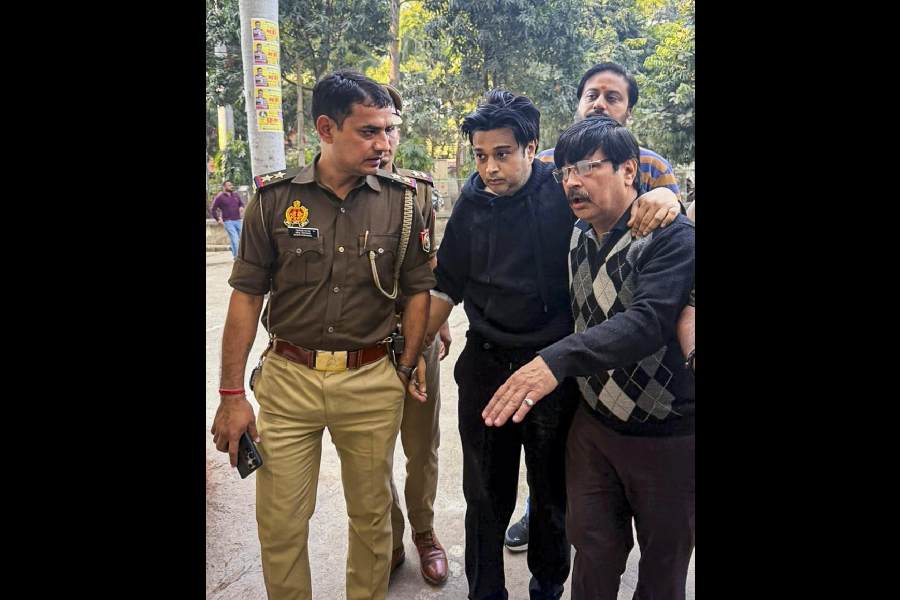

| Mariane Pearl with Jolie |

After more than four years of conflict in Iraq, at last it is evident in American public life that the country is at war. For a long time you could never guess, from anything you saw or heard in America, that the country was fighting such a protracted and bitter war elsewhere. But, finally, we know that Americans know they are at war, because the war has begun to translate into narratives in Hollywood and the American media. Nothing is really real in America, unless it is on television and in the movies. In this sense, Iraq has finally become real.

The new Hollywood film, A Mighty Heart, tells the story of the few terrible days between the kidnapping of Daniel Pearl in Karachi in January 2002, and the news of his death by decapitation in February of the same year. Danny Pearl was the south Asia bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal, living in Mumbai. Together with his wife Mariane, also a journalist, he was out on an assignment in Karachi in early 2002, a trip he did not survive. The film reconstructs the passage of that gut-wrenching month for Mariane, who was pregnant at the time, Danny’s colleague and friend, Asra Q. Nomani, and others who waited for him to return, and fruitlessly tried, in the meantime, to find his kidnappers. The crime was eventually traced to Omar Saeed Sheikh, who was sentenced to death in Pakistan and has challenged this verdict, and to Khaled Sheikh Mohammad, detained in the US custody at Guantanamo Bay.

Asra Nomani, formerly with the Wall Street Journal and now teaching at Georgetown University, in a piece in The Washington Post (June 24) entitled “A mighty shame”, denounced the film for not being about Danny. Strictly speaking, she is right, but this is not a flaw in the film. It is about Danny’s death, not about his life. It is about how his wife, parents, siblings, colleagues, friends and others — American and Pakistani officials, intelligence and the press — lived through the awful weeks between his disappearance and murder. Also, the screenplay is based on Mariane Pearl’s 2003 memoir of the same title, and both Mariane and Asra Nomani served as consultants to the scriptwriter, John Orloff.

Before I go any further, let me put my cards on the table. I knew Danny and Mariane Pearl. I met them in Bangalore and Mumbai in 2001. I also happened to spend all of September 2001 in New York before, through and after the destruction of the World Trade Center. It’s been about six years since 9/11 and Danny’s gruesome death in February 2002, and I can say honestly that I have not been able to get over either event. Like countless other individuals, not least Nomani, I too am unable make my peace with what happened.

A few months ago, I watched The Journalist and the Jihadi, an HBO television documentary about Danny Pearl and Omar Sheikh, which left me with mixed feelings. I also watched The Road to Guantanamo, directed by Michael Winterbottom, director of A Mighty Heart. It was Winterbottom’s chillingly realistic style of filmmaking, the overwhelming cinematic power and strong political message of The Road to Guantanamo that moved me to watch A Mighty Heart, even though I had my doubts about the wisdom of casting a Hollywood superstar like Angelina Jolie in the role of Mariane Pearl. Hats off, once more, to Winterbottom, who not only gets a convincing performance out of Jolie, but also manages to prevent her from distracting viewers with her presence or diluting the nerve-wracking narrative.

As someone who knew Danny and Mariane, I was relieved that the film did not depict Danny’s captivity or the ghastly way in which he was killed, despite the fact that the kidnappers themselves released a video of their dreadful act, and this was widely circulated on the internet. Winterbottom conveys the unspeakable nature of what happened to Danny without visualizing it in any way, and one cannot be sufficiently grateful to him for showing such restraint when graphic and gratuitous torture scenes have become routine in the movies. In keeping the inhuman mode of his death off-screen, the director showed respect for Danny’s life and work, and for the irredeemable pain of those who loved him.

What I found shocking about this film, then, was not any of the things that I had been apprehensive about: misplaced focus (Nomani’s criticism), casting Jolie (a controversial choice, by all accounts), and depicting Danny’s atrocious end (the road, thankfully, not taken). Rather, what struck me as most unfortunate was the way in which Karachi came through as not merely the city where this sordid saga unfolded, but as a space that fundamentally resists deciphering. It appeared to be a frightening and incomprehensible palimpsest of urban chaos, poverty and Islamic terrorism, teeming with Muslim men who are scarily numerous, devoutly religious, and horrendously violent no matter which side of the law they happen to be on. Even the sympathetic “Captain” Javed Habib, the chief of the Pakistani CID’s counter-terrorism unit (impeccably played by Irrfan Khan), who is sensitive to Mariane’s agonizing circumstances, can torture a man almost to death and then proceed directly afterward to the mosque for his morning prayers. It seems we cannot expect anything but cruelty in this place, at once hellish and baffling.

Winterbottom is too politically discerning a filmmaker to portray Karachi or Pakistan with the outright Islamophobia that makes Bernard Henri-Levy’s book, Who killed Daniel Pearl?, so odious as to be unreadable. Winterbottom shows us that Mariane Pearl never lost her moral compass even in the immediate aftermath of her husband’s brutal assassination, and publicly came out a day or two later to say that ordinary Pakistanis suffered as much from acts of terror as did Westerners like her. Who would have experienced Karachi as sinister if not Mariane, but she desisted from indiscriminate blame. And yet, in Winterbottom’s vision, Karachi is nightmarish in a way that is subtly connected to its cultural essence, its identity as an overpopulated, poor, lawless and, worst of all, radicalized megalopolis, located in an underdeveloped Muslim country, a place of evil where civilized, trusting and competent Americans and Europeans enter at their own peril and probably end up dead.

Danny Pearl was a superb journalist and a cosmopolitan man. He was an American Jew married to a French Buddhist (Mariane is actually part Afro-Latina Cuban, and part Dutch). He lived in Mumbai, and he loved south Asia. He went to Karachi, his beloved Mumbai’s sister city, to follow a story, like any reporter worth his salt. Yes, he died in a way that no one should die in. He is, and will always be, mourned by everyone who knew him. The men who abducted him were anti-Semitic and anti-American, and killed him for what, according to them, he stood for (his religion and his country). They hated him for an ideology he did not espouse, and attempted to get symbolic caché out of his totally undeserved slaughter. But as someone who interacted with him, even just a little bit, I am certain that he did not perceive Karachi, Pakistan or Muslims with the racism, prejudice and otherness that scar Levy’s whodunit, and taint even so fine a film as Winterbottom’s A Mighty Heart.