Few could have said it with the dark wit of Milan Kundera in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. When Czech Communist Party leader Vladimir Clementis was disgraced and executed, he was "airbrushed" out of an earlier photograph that showed him standing next to Klement Gottwald, the future President. What stood in his place ever afterwards was a blank wall: erased past vacuuming the future. After all, a tabula rasa in the future is more easily appropriated by rulers to engrave their agendas upon. Because, "the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting."

This reference came to mind at Ganges Gallery's recent show, Things Lost, Remembering the Future. In presenting 14 participants from eight South Asian countries - where the manipulation of minds through rearranged histories seems rampant - it treads that besieged area where artists wish to hold on to, what curators Kurchi Dasgupta and Amritah Sen describe as, "the small, the forgotten... as opposed to the official and the monumental."

Frighteningly enough, though, such loss may not always be intentional. In the Record Room series of David Alesworth (Pakistan/ UK) the past becomes a precarious, chancy reconstruct, depending on what may be excavated from the mountainous chaos of yellowing, brittle files in careless official archives (picture, bottom). Leaving out of reckoning the vast field of unrecorded voices, of course.

But loss, the erosion of the past, is the steady refrain in the subcontinent where society was once thought to be changeless. Huma Mulji (Pakistan) perceptively sums up the onslaught of change in a simple picture: of baker Karamatulla, who sold the bread he baked daily in his run-down little home in an area which has suddenly turned into prime land. His small family enterprise now stares at extinction in a competitive market as inevitably as does his little home before the juggernaut of property development.

Bangladesh's Tayeba Begum Lipi retreats to a memory that's too private to be decoded. But Mustafa Zaman (also Bangladesh) teases intriguing murmurs out of negatives of passport photographs laid over hazy images beneath in his series, Witnessing the Witnesses: the viewer witnessing the stunned, spooky witnesses to unspoken events. The layering conjures a fragile twilight zone of garbled memory evaporating before it can be quite defined.

Aye Ko (Myanmar) brings to his digital photograph a concentrated, theatrical gesture of individual resistance. But the fissures within Myanmar aren't political alone. As Thyitar, a Muslim artist made conscious of her difference from the others by those others, reminds you. But a single frame can hardly compensate for the performance you don't get to see. What Pala Pothupitiye (Sri Lanka) reminds you of is how identity is yoked to the accustomed earth: homeland and its maps. In this case, of two districts of the island state. Green and mustard patches, embellished with stylized waves, the tiger (of the Tamils?) and the decorative lion of their national flag, make for an engaging work but it mutes the conflicts his note mentions. His compatriot, Thisath Thoradeniya, displays an aerial map of Bangalore, with iron tools arranged on it. A striking juxtaposition that stokes multiple suggestions.

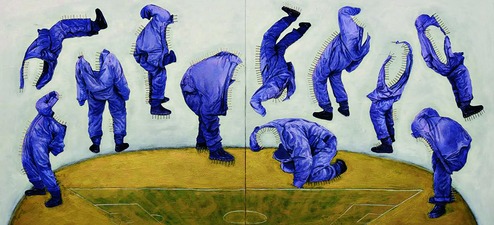

Maimoona Hussain (Maldives) speaks at a more intimate level, evoking the poignant vulnerability of The Female Child, while Sen (India) brings a universal resonance to the experience of disintegration, of "living in bits and pieces", as the integrated ideal symbolized by the Vitruvian Man falls apart. That sense of disintegration persists in Dasgupta, who lives in Nepal. She cunningly wrests from adversity a metaphor for the crisis that followed India's blockade of the land-locked country in 2015 by stitching together bits of canvas when she ran out of art material. And Sunil Sigdel (Nepal) translates a performance into a single, arresting visual which comments on the irony of subcontinental labourers dying - one every two days, says his statement - while building, in blue overalls, the infrastructure in Qatar where the world will compete for the gold in football in 2022. Hence the title, Blue Slavery in Golden Construction (picture, top).

The video of Nepal's Ashmina Ranjit, who walks backwards to retrace her life's journey from Kathmandu valley to the capital city, seems rather futile. But Rahaw Omarzad's (Afghanistan) footage, beginning with a ground-level view of walking feet, suddenly throws a knockout revelation: the ragtag recruits have prosthetic legs, living signposts of the serial devastation that began in 1979. Another sequence in which books tumble, pages flying, inscribes a Fahrenheit 451 concern into this Afghanistan epic of things lost. Only, it's a veritable loot; of history and heritage, leaving the future bereft, rootless, without memory.