The pandemic has left most people and institutions scrambling for solutions to unprecedented difficulties. With schools closed for months, teaching has shifted online to a great extent. While formulating methods and material for online communication cannot be easy for teachers, trying to learn in a new way can be unimaginably difficult for children, especially the younger ones. This year’s Annual Status of Education Report, produced by Pratham, would normally have been the ‘basic’ study of district, state and national estimates of rural children’s schooling and foundational learning. But current conditions led not only to a survey via telephone but also to the focus being shifted to the way the pandemic has affected children’s learning in rural India. The survey included 59,251 children aged five to 16 from 52,227 households and 8,963 schools.

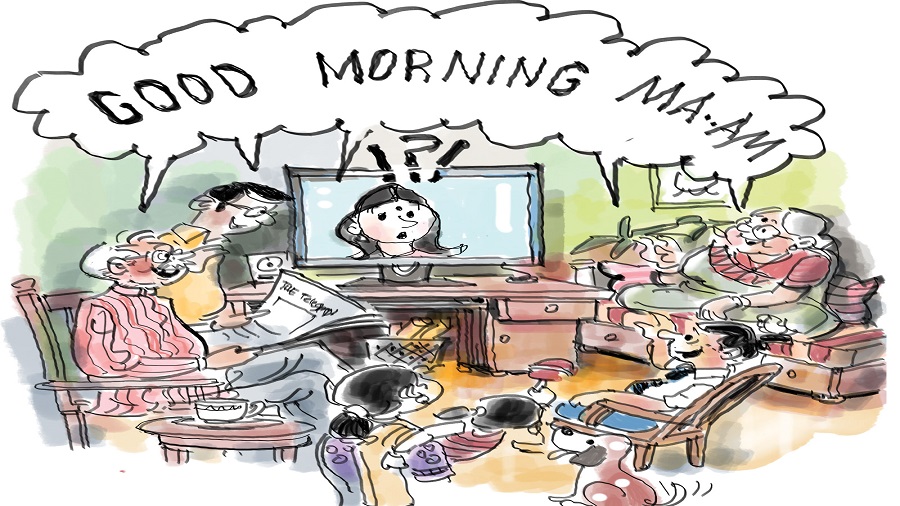

That access to remote learning cannot be universal is of primary concern the world over, not only because of general ‘learning loss’ but also because this would deepen already existing inequities. The results can be tragic; in India and elsewhere, exclusion has led to depression, and even self-harm. The ASER report says that only 11 per cent of the surveyed children can attend live online classes. Schools were able to reach learning materials to about 80 per cent of the children, and 24.3 per cent had not received anything during the week of the survey, chiefly because they have no access to a smartphone. This actually means a huge number of children. Smartphones have become fundamental to lessons now. Parents are alert to this; many have bought smartphones for their child’s lessons. Even then, households with more than one child still face difficulties, although the support from parents, other relatives — according to their learning levels — and older siblings, even neighbours who have smartphones, is one of the more heartening aspects of these deeply troubling times.

The lower enrolment figure — compared to 2018 — especially among the youngest children may in large part be driven by the pause in admissions because of the pandemic, although this cannot be fully determined till schools reopen. Meanwhile, more children have moved to government schools. That may be because money is running short at home, or because of fears that private schools may shut down. The survey of states shows that schools in West Bengal have been most successful in reaching textbooks to the children, and the state has also reduced the dropout rate. The policy of distributing food grains to the pupils’ families in lieu of mid-day meals seems to have helped in this.

What matters most in this crisis is the need to get through to those children who are being excluded from lessons. The students who have partial or full access to remote learning, too, may not find the going smooth. Learning outcomes, recorded later, may help decide the approach that would be needed to neutralize the damage inflicted by the pandemic.