HONORIS CAUSA: ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF AVEEK SARKAR Edited by John Makinson, Allen Lane, £20

Aveek Sarkar likes paradoxes and puzzles, and he is something of a paradox and puzzle himself. He is perhaps the first successful Bengali entrepreneur since Acharya P.C. Ray; and almost certainly the first right-wing Bengali intellectual since Jadunath Sarkar. And he may be the only Captain of the Royal Calcutta Golf Club to have preferred the dhuti-panjabi to plus fours.

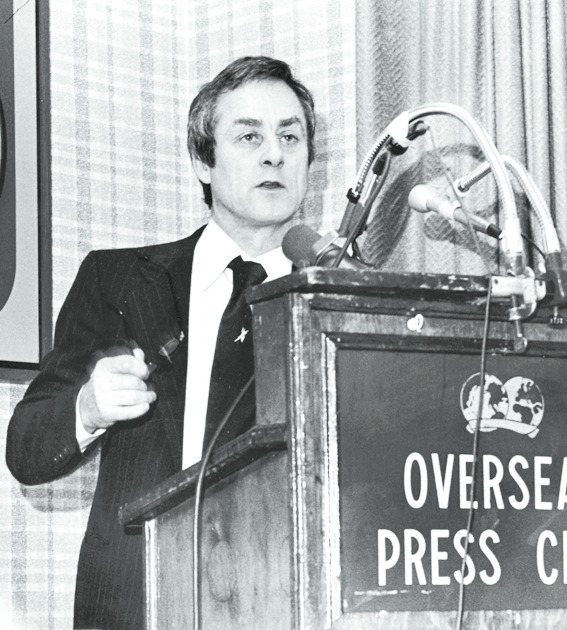

In his preface to Honoris Causa, the editor, John Makinson, wistfully notes that this is not a book by Aveek Sarkar, nor (what would have been even more delightful) a book on Aveek Sarkar. It is, rather, a collection of essays on his varied interests and obsessions, from a sterling set of contributors, and published to coincide with Aveekbabu's seventieth birthday. The book begins with an essay by Harold Evans, former editor of the Times and the Sunday Times. Evans provided an occasionally cynical but always insightful analysis of how the digital age has transformed the presentation and reception of news. He welcomes the easy access to recorded facts, which "has already turned every cub reporter into Clark Kent". However, he complains that the priorities of news websites are no longer set "by hot-blooded journalists, but by cold algorithms contrived by engineers and software designers". As for television, a medium which bridges the new and the newer, it remains "indispensable for live events; in the US presidential elections, the debates are essential viewing if only for comedy or caricature" (this was written even before Donald Trump declared his candidature!).

David Bell, a former chairman of the Financial Times, offers a crisply written piece on the complex relationship between owners and editors. "Editorial independence may be much prized", he remarks, "but it is comparatively rare around the world." He upholds the FT as an example of a paper where the proprietors have rarely, if ever, trodden on the toes of the editor or the staff. This may be sound ethics, but also good business, for "as a result, readers come to trust what they read, which creates and sustains a brand that is commercially very valuable". Like Evans, Bell worries about the distortions the digital age can bring. The way text is presented and packaged can hugely influence how news is received, while Photoshop has made the Stalinist airbrushing of Leon Trotsky et al. seem very amateurish indeed.

Bell is followed by Charles Gray, the judge in the famous/notorious case of David Irving, a historian charged with being a Holocaust denier. Comparing freedom of expression in India and Britain, he not unexpectedly finds it more constrained in the former. One reason for this (which Gray does not mention) is the malevolence of our political class; the proclivity of netas of all parties to encourage goons who harass, intimidate and occasionally eliminate writers and artists whose views they do not agree with. Gray focuses rather on weaknesses in our legal system and the timidity of our judges, who need to be aware of, and be willing to follow, the remarks of the 19th century British judge Lord Coleridge: "The importance of leaving free speech unfettered is a strong reason in cases of libel for dealing most cautiously and warily with the granting of interim injunctions".

Aveek Sarkar has made it his business to be fully acquainted with the technical and legal aspects of newspaper publishing. But he also has an abiding interest in type, and so we have here a lavishly illustrated offering by the designer Fiona Ross. She skilfully traces the transformation from handwriting and calligraphy on the one hand to type, print, and screen on the other. The scripts of South Asia, notes Ross, have "the greatest visual diversity"; appropriately, her examples come from Gurmukhi, Tamil, Urdu, Malayalam, Kannada, and, not least, Bangla.

The mlecchas having had their say, natives of Aveek Sarkar's own city offer tributes to him. The distinguished art historian Pratapaditya Pal explores the connections between Ananda Coomaraswamy and Calcutta, his text animated by elegant illustrations. In the early years of the 20th century, Coomaraswamy came often to the city, in search of painters and paintings. What he saw and collected were to inform his authoritative studies of Indian art. Pal succeeds in taking the man (and critic) out of the "metaphysical mystique" he surrounded himself with, by showing how Coomaraswamy's work grew out of his relations with the dealer Bharany, the artists Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, and the editor Ramananda Chatterjee.

In a short piece, Mahan MJ, a monk in the Ramakrishna order with the formal name Swami Vidyanathananda acquaints us with the mystery and wonder of mathematics, and the idiosyncrasies of its greatest exponents. When we read of how Grisha Perelman refuses to leave his St Petersburg home (not even to receive the Fields Medal), or when the great Alexander Grothendieck abandons a high academic post for wanderings in the Pyrenees, we must be grateful that Mahan himself has merely become a monk who continues to teach.

The longest and most learned piece in Honoris Causa comes from the Oxford Sanskritist Alexis Sanderson. In a magisterial survey of early Hinduism, he explores how different religious traditions came to coexist, largely for practical reasons than on account of a principled tolerance. In their writings, Vaidikas were often extremely hostile to Saivites, and vice versa, as vividly demonstrated by the acidic extracts that Sanderson so expertly translates for us. Yet the exigencies of political power allowed them to tolerate one another. For much of early Indian history, writes Sanderson, "no one religious tradition was in a position of such strength that it could rid society of its rivals, a balance of power sustained by the policy of governments". Kings consolidated their rule by eschewing sectarianism; practising one faith without oppressing another, and often taking their consorts from religious traditions other than their own.

Sanderson is too scrupulous a scholar to make connections with the present. But to this Hindu, it does seem that in the millenia before the Mughals, Hindu ideologues were often intolerant in theory but rarely so in practice. Now, alas, it is almost exactly the reverse, a pro forma allegiance to the pluralism of the Indian Constitution accompanied by the active demonization of other faiths on the ground.