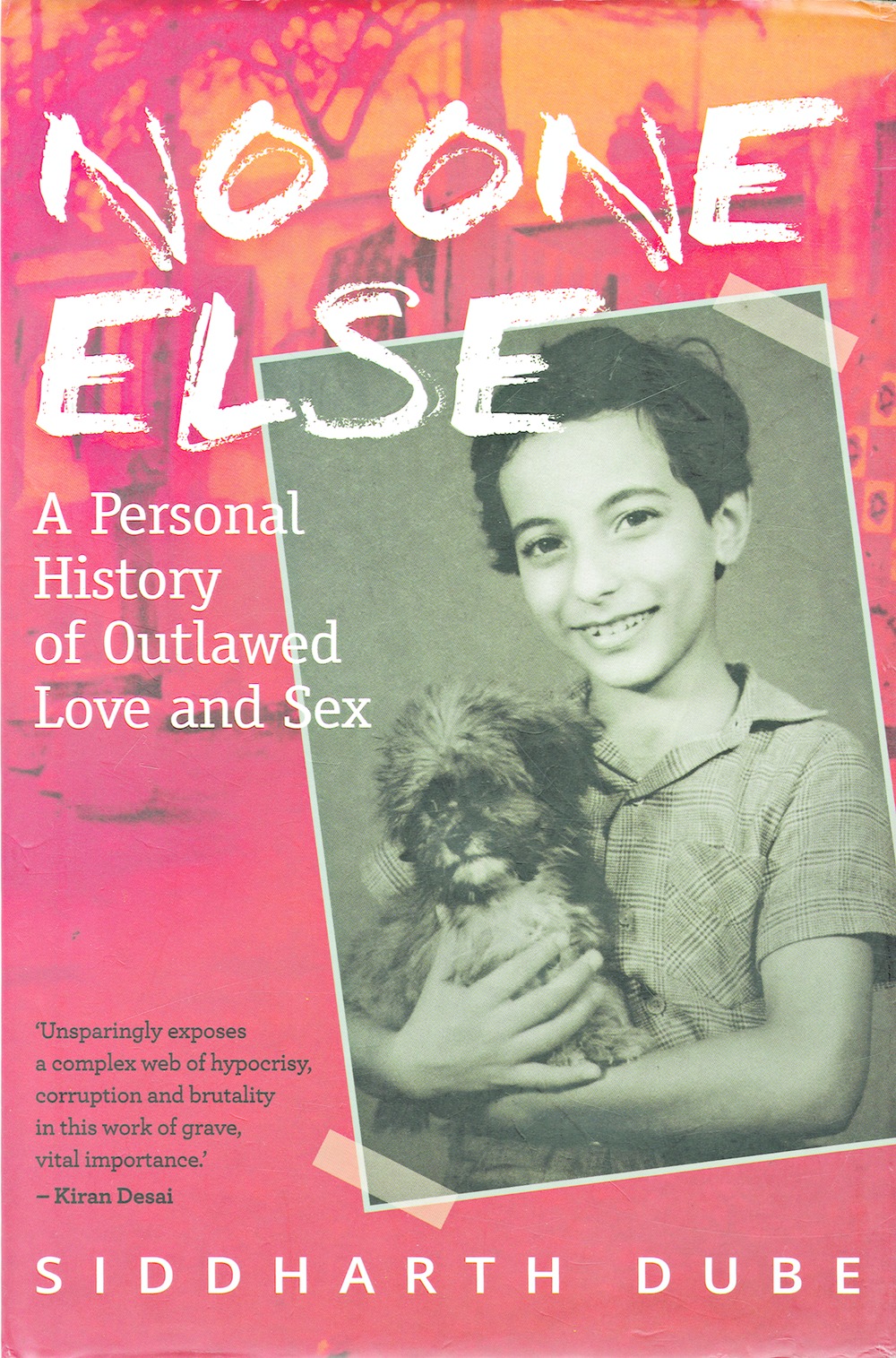

NO ONE ELSE: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF OUTLAWED LOVE AND SEX By Siddharth Dube, HarperCollins, Rs 599

Can history be personal? Official histories often tend to serve as an alibi of existing power structures by stifling the voices of marginalized people. Memoirs, autobiographies, oral narratives and similar texts can serve as interesting alternatives by recovering their voices and bringing to the fore their non-academic ways of seeing the world. We now have a burgeoning archive of personal accounts of women, working-class individuals, sexual minorities and people of colour, who have significantly expanded our understanding of social realities. Judging from this viewpoint, Siddharth Dube's memoir, No One Else: A Personal History of Outlawed Love and Sex, seems like a welcome addition. By linking his own life history to the larger trajectory of the gay rights movement, histories of public health and activism for rights of sex workers, the author exposes the overt and covert ways in which sexual minorities are routinely subjected to a myriad forms of discrimination: institutional, social and personal.

The author's personal struggle with issues of sexuality started early in his life. Picked on by his classmates for his "effeminacy" in school, he found comfort in the giddy romances of Barbara Cartland and the Mills and Boon series. According to Dube, the fear-based schooling system and its associated violence not only scars the victims but also colours how perpetrators of such peer violence go on to relate to issues of masculinity, the relation between sexes and attitudes towards the weak.

At Doon, he had the harrowing experience of dealing with prefects, who tormented younger boys often with the tacit support of the housemasters. While it was an open secret that many of the senior boys forced themselves sexually on the younger lot, publicly, they carried out "witch-hunts" to root out homosexuals in the school. Later on Dube was to find out that the homophobia, so ingrained in the environs of the Doon, continued even within the apparently liberal space of a leading English daily, where one of his colleagues - a "mild-mannered man from Calcutta" with a "marked British accent" - was the enduring target of openly homophobic slurs.

The book would have been another trite account of maudlin self-pity, had the author not balanced his personal experiences with his incisive analysis of Indian attitudes towards sexuality, governmental apathy and societal hypocrisy. Each theme is fleshed out in vivid detail in the book prodding him to come up with some striking conclusions. For instance, he effectively juxtaposes the relative public silence about the criminalization of homosexuality with a candid account of how "non-anglicized" men in rural and semi-urban settings - his list includes two brothers in a Jat village, a rural volunteer in Bihar, two policemen outside the Ramnagar fort and a security officer at a Madras hotel - treated same-sex desire with astonishing tolerance. And yet, many of those who habitually led the life of a closeted homosexual also had warped notions of masculinity coupled with misogyny and internalized homophobia.

The book is as unsparing towards governmental ambivalence as it is towards societal hypocrisy. Pre-colonial cultures of qualified tolerance towards same-sex desire were altered beyond recognition under the 200-year colonial rule. Masculinist education coupled with prohibitory laws - such as Article 377 along with a host of discriminatory laws against sex workers and hijras - pushed the sexual minorities into a dark space, where they found their fundamental rights routinely violated. Nowhere is this clearer than in the bone-chilling accounts of mistreatment of some of the earliest AIDS victims in India. Dominic D' Souza, Goa's 'patient zero' of the dreaded scourge, was picked up from his home and left to rot in an abandoned tuberculosis sanatorium, amidst "rat[s] and pigeon droppings". In Dube's poignant account, the wasted lives of D' Souza and countless others, can be vividly apprehended. But the harshest words are preserved for the West, especially the US government and its stooges - institutions like the World Bank. Dube shows how the AIDS relief measures are used as a ruse to shove expensive branded American drugs down the throats of poor AIDS patients in Africa and how taxpayers' money collected from debt-ridden countries around the world pays for the subsidized luxuries of World Bank employees.

For a writer used to producing academic works, Dube shows promise in writing a memoir. Nonetheless, the book flags a bit in parts. Perhaps there could have been more on his relationship with Tandavan, the eclectic French Bharatnatyam dancer and the one true love of his life. A memoir that starts with an intimate account of attaining sexual maturity, confronting personal fears and discovering the joys of love and friendship, seems to become a recycled version of his previous works, by the time it ends. The author concludes with a sense of dejection at the Supreme Court's 2013 reversal of the Delhi High Court's ruling that had earlier declared Article 377 unconstitutional. Dube seems to have internalized the idea that State's recognition of a gay person's selfhood is the be-all and end-all of gay politics in India.