THE DISCREET HERO By Mario Vargas Llosa, Faber, Rs 799

Where have all the women gone? Numerically, there is no dearth of them in Mario Vargas Llosa's The Discreet Hero; in fact, the reader almost trips on their hems from scene to scene. But they do not engage the mind; they are just so many pawns to carry on the game. The men are all paired off: Felicito Yanaque, the owner of Narihuala Transport Company in the Peruvian city of Piura, is married, however unwillingly, to Gertrudis, whom he had met as a young truck driver in El Algarrobo boarding house, where she was the formidable woman owner's daughter, a cross-eyed, slovenly "broad", always smelling of onions and garlic. As if this stereotype were not enough, the reader meets Gertrudis after she has been "hard-working and self-sacrificing" throughout the difficult years when Felicito struggled to build up his business, and now always wears flip-flops and a robe that looks like a cassock, evidence for her detached husband that she has become religious: "It seemed to him that over the years Gertrudis had turned into a piece of furniture, that she'd stopped being a living person."

Are the other women any more "living"? Felicito, unfortunate in the challenge that drops on to his doormat out of the blue, is fortunate in being surrounded by women. There is Josefita, his secretary, "of the broad hips, flirtatious eyes, and low-cut blouses" whose fate is, inevitably, to be desired and wooed by the lecherous Captain Silva, the perspicacious policeman who ultimately exposes the plot threatening Felicito. Then there is Adelaida, the "holy woman" and one of Felicito's two mentors, who sits in her small shop selling "herbs, figures of saints, notions, and odds and ends", the "ageless mulatta, short, fat-bottomed, big-breasted", clad, inevitably again, in a coarse, clay-coloured tunic or habit. Not even Mabel, Mabelita, Felicito's pretty little open secret he had set up in a separate house, is allowed to step out of her expected statistics: "She still had her gymnast's figure, her narrow waist, pert breasts, and round, high ass that she still shook joyfully when she walked." Her hair, mouth, teeth and "radiant" smile are along the same lines. The author obviously could not have Felicito fall in love with the distinctly unattractive Gertrudis while being married to a provocative Mabel. That would lead him far away from his theme of discreet heroism in a time of growing prosperity and accompanying greed. Women, at least in this novel, have no part in this heroism. At most, Gertrudis is granted a kind of reward at the end, for being both victimized in and repentant about her youth (although faultless) and having the 'right' responses (although it must have hurt) when the plot is exposed.

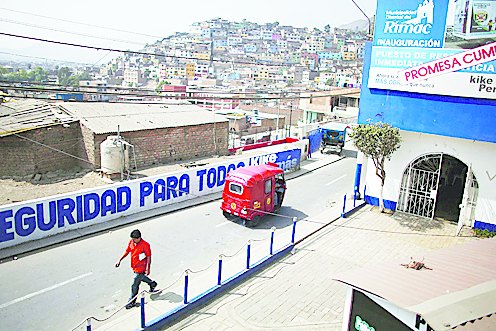

Who, then, is the discreet hero? Peru is changing for the better, and localities in Piura that were once an "ancient labyrinth of streets, alleys, crescents, dead ends, empty lots" wore a different look, had a different feel: "The dirt streets were paved in asphalt, the houses were made of brick and cement, there were some office buildings, street lighting, not a single chicha bar or burro left in the streets, only stray dogs." What remain unchanged are corruption, greed, the tussle for power and money; threats, plots, and crass deceit to grab what someone else has made with ceaseless work and dedication. To stand up against such criminal demands needs a quiet, unbending determination that the discreet heroes of the novel display. Felicito Yanaque in a small town, Ismael Carrera, the owner of a thriving insurance company in Lima, a widower who decides to marry his housekeeper and maid, Armida, in order to foil his two loutish sons who cannot wait to see him dead, Rigoberto, his manager, and Narciso, his loyal driver, black and poor, both of whom agree to witness his secret marriage and watch their worlds fall apart as the elderly bridegroom goes off to honeymoon in Europe, may all be discreet heroes. Carrera may be considered a little short on discretion, if the plot is any indication, but there can be no doubt about the others. The two stories in Piura and Lima meet and merge in the most unexpected, even funny, way, and Llosa's unmistakable touch in bringing together small town and big city, gringos and mulattos, sharks and innocents, could perhaps redeem his use of stereotypes to get to the point of his fable.

For Armida, the inconspicuous maid who appears silently at her master's elbow to attend to his smallest need, is transformed into this elegantly attired, softly spoken, modest, un-grabbing perfect rich man's wife after her honeymoon in Europe, another moral melodrama type difficult to digest. Even Lucrecia, representing the closest approximation to an equal partner in the novel, does not really fulfil her promise in spite of her enthusiastic participation in erotic games with her husband, Rigoberto. But it is not women alone that Llosa shrugs off. Carrera's twin sons, Miki and Escobita, are the kind of pasteboard villains got up to show children that badness is comic. Does Llosa mean to be funny here? The sons of Rigoberto and Felicito are made of different creative genes. What does emerge within the theme of greed and heroism is a narrative flowing along the cross-generational currents between fathers and sons, full of the turns, folds and creases in which irony resides side by side with melodrama. The last is very deliberately hyped up within the narrative by the rapacious, tireless media that infiltrate and pervade the lives of all the characters, making the whole idea of discretion, privacy or quiet heroism seem ludicrous. This is one aspect of progress that gives Llosa scope for the unchecked play of satire.

Llosa's technique of presenting action by juxtaposing past exchanges with present dialogue captures the irony and doubles the sense of immediacy. It adds an extra thrill to the thriller-like story of Felicito. Yet the world evoked is far from narrow. Rigoberto struggles to preserve his little "space of civilization" with his collection of paintings, music and literature that keep alive in him the dream of a culturally magical Europe, but he realizes that such spaces cannot always be saved from the "barbarism" of the time. More disturbing to his, and Lucrecia's, peace of mind are the experiences Lucrecia's son, Fonchito, beloved of both, keeps reporting. He keeps meeting a man called Edilberto Torres in the most impossible places and has quite incredible conversations. Is it the devil himself, or is he a ghost, or is Fonchito, tender, good, serious boy that he is, lying? Neither the psychiatrist nor the priest believes so. As the father-son relationship continues to founder on the shoals of this inexplicable visitation, the reader is left wondering about truths and lies, about realities, moralities, love, faith, dreams and deceits.